It’s been a while since I blogged about New Zealand and our 2018 trip, but I’ll correct that today, since there was one garden omitted – and it was my favourite. If you recall, in my last blog we were sailing back to the North Island from the South Island and settling ourselves into New Zealand’s beautiful capital city of Wellington for the final chapter of our trip. Today, I want to take you to what was my favourite public garden of our entire 3-week tour, Otari-Wilton’s Bush (whose proper name is Otari Native Botanic Garden and Wilton’s Bush Reserve, but I’ll call it OWB for short). Let’s walk from the car park through the main entrance gate or warahoa…..

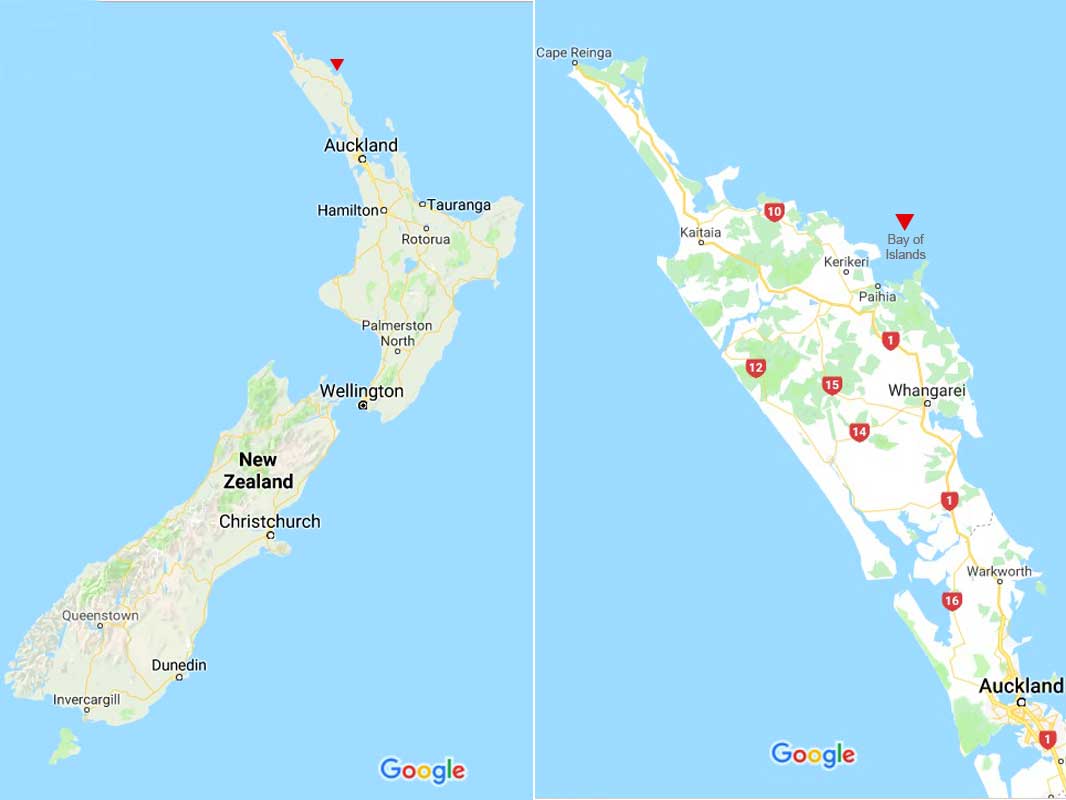

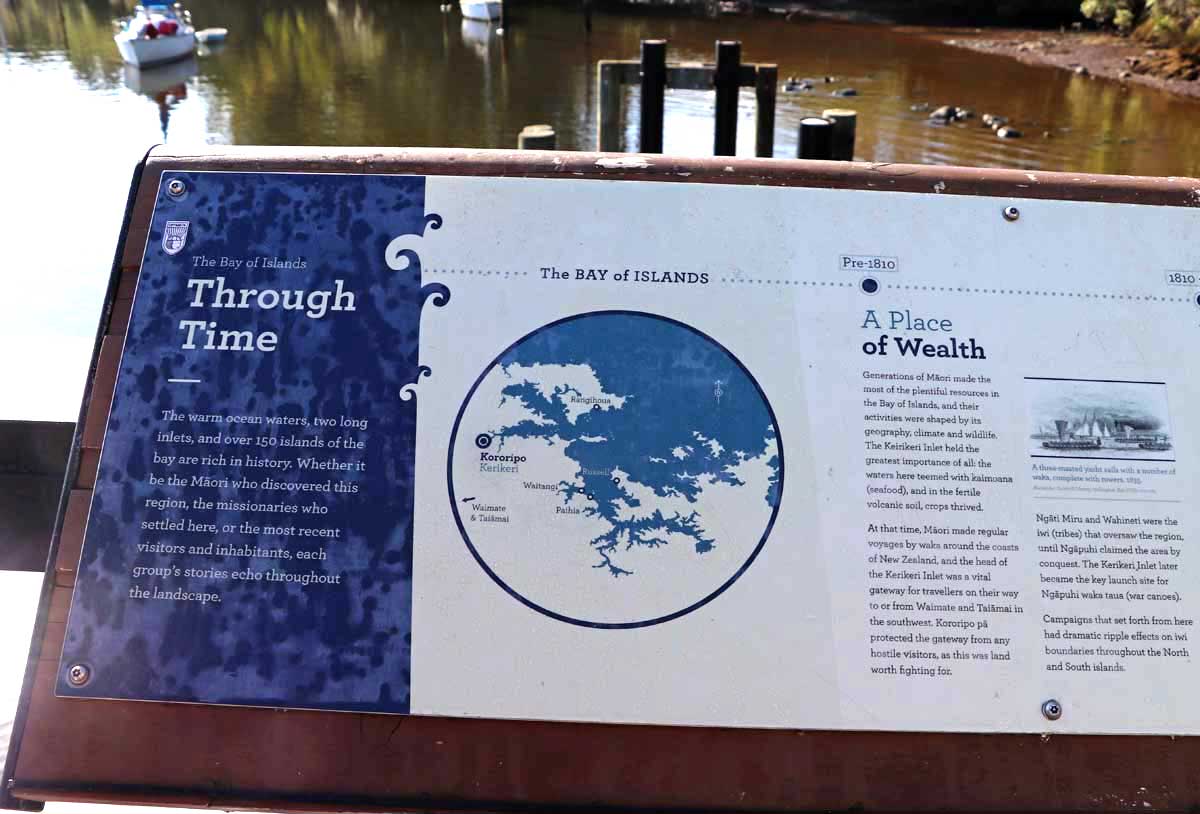

….. past the Kauri Lawn and the familiar trunks of the kauri trees (Agathis australis) we’d fallen in love with a few weeks earlier on the Manginangina Kauri Walk in the Puketi Forest near Bay of Islands, on our Maori culture day.

The path leads past interesting New Zealand natives towards the information centre where we can……

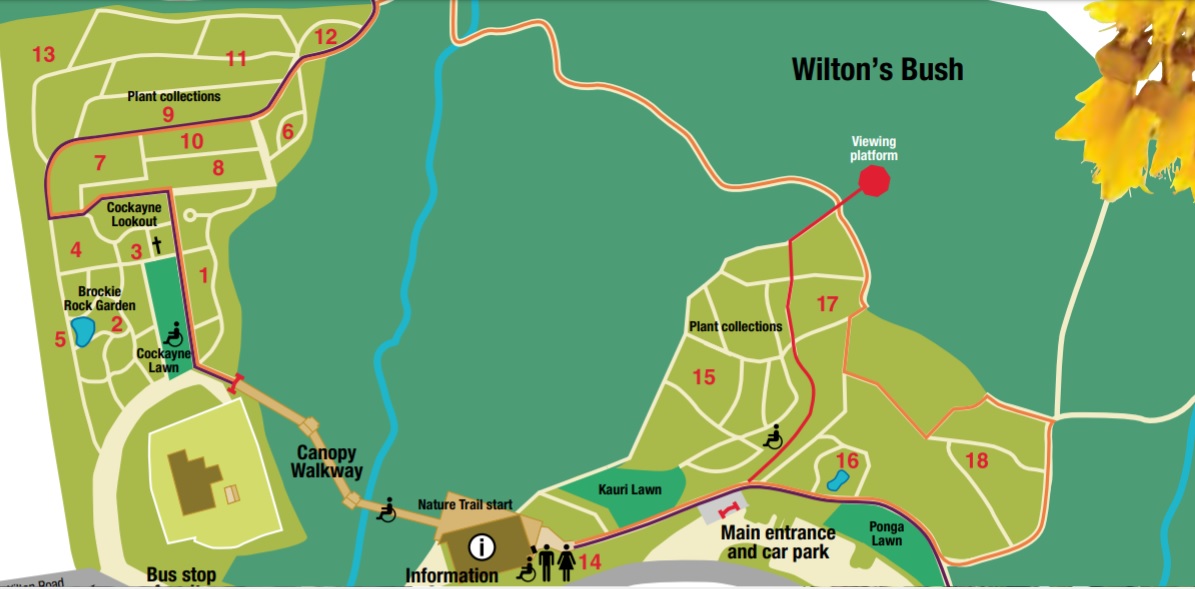

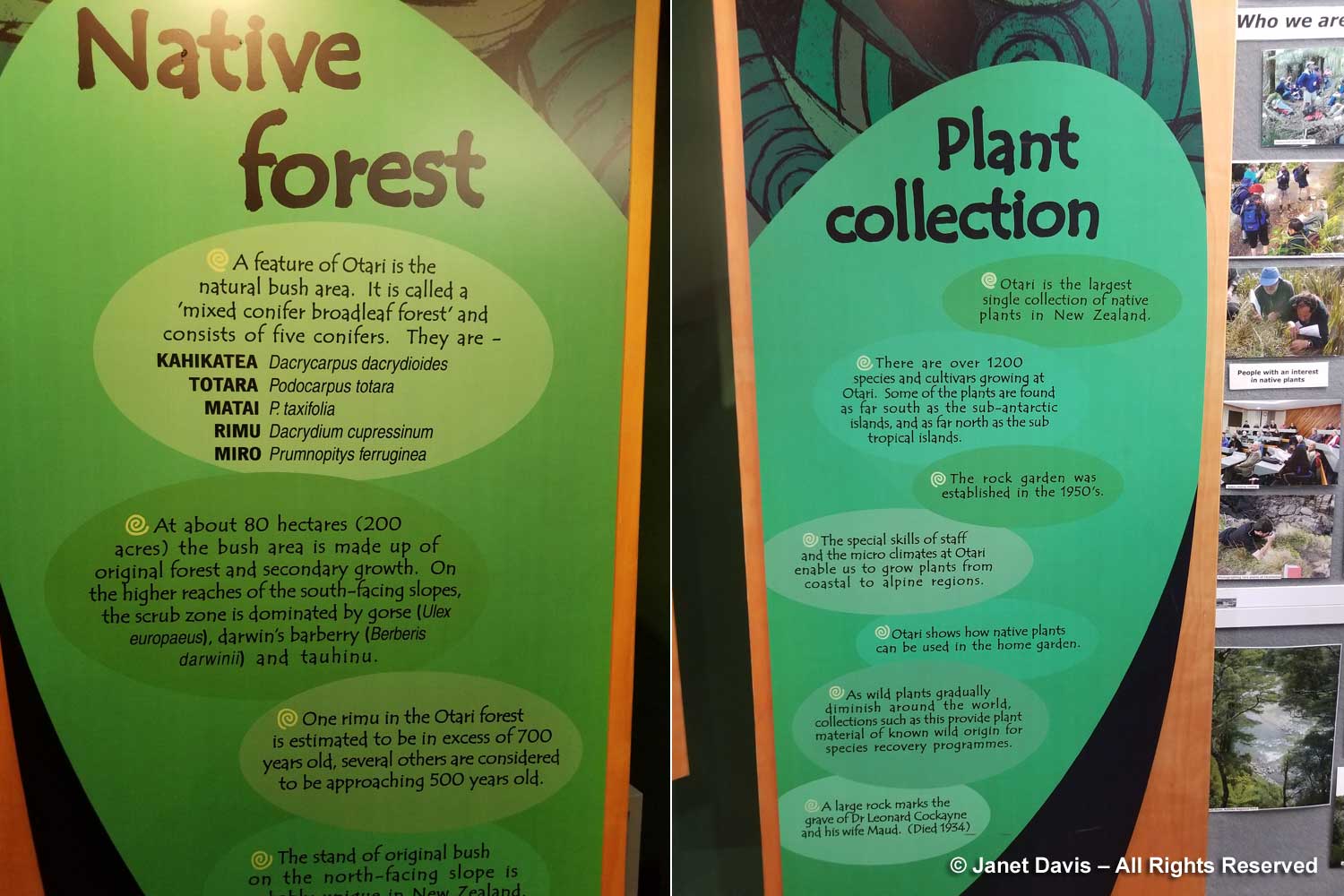

….. find a map. This place is massive! There are ten kilometres of walking trails over 100 hectares (247 acres) of native podocarp-northern rata forest featuring 5 hectares of gardens containing half of New Zealand’s native plants. In total, there are.1200 species, hybrids and cultivars of indigenous plants, and we have such a short time to visit! On that note, I should add that there was a reason why it took me so long to get this blog together: the complexity of the garden and our speed rushing through it meant that I didn’t feel I could do it justice without researching it a little more than the other public gardens we’d visited, which were more straightforward…. rose garden, perennial border, etc. There is not that kind of typical botanical garden approach here at OWB. It’s all about native plants and their conservation! I could have spent two days there, easily

Because it’s difficult to read the map (click on it or download it for a better look), here is the legend:

1 – Plants for the home garden

2 – Brockie rock garden

3 – Wellington coastal plants

4 – Grass and sedge species

5 – Threatened species

6 – Hebe species

7 – Rainshadow garden

8 – Flax cultivars

9 – Pittosporum species

10 – Coprosma species

11 – Olearia species

12 – Northern collection

13 – Divaricate collection

14 – Gymnosperm (conifer) collection

15 – Fernery

16 – Alpine garden

17 – Dracophyllum garden

18 – 38

19 – Broom garden

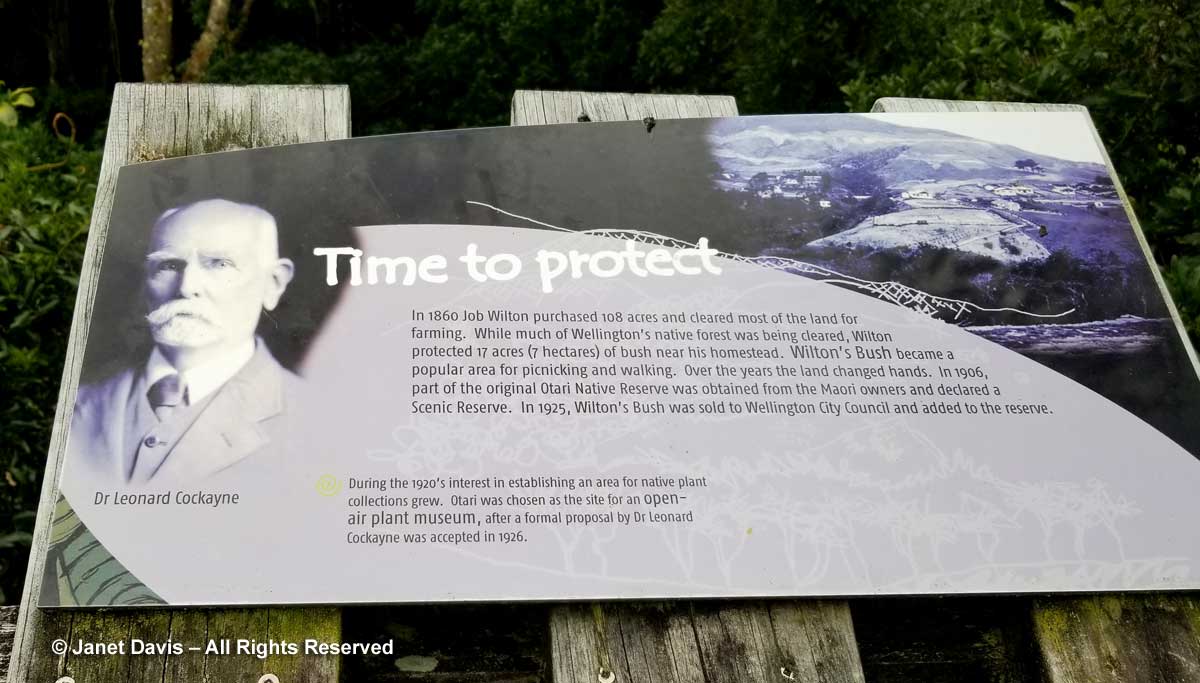

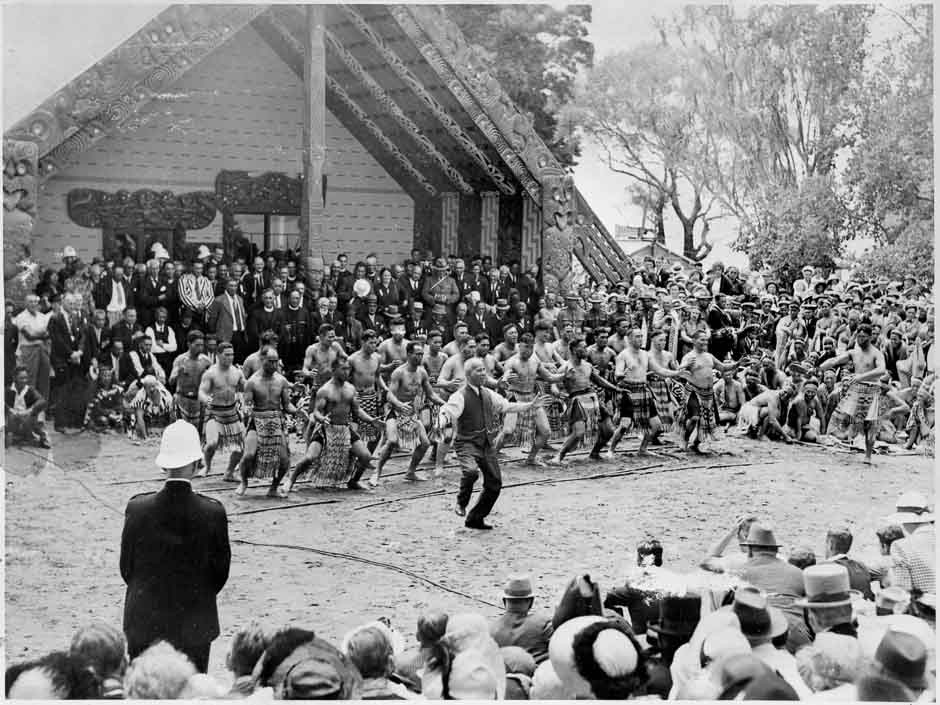

The garden and surrounding bush has a complicated history, from the Maori first inhabitants – Taranaki tapū or sub-tribes – who migrated to the general area in 1821 from the Wellington region; to the arrival of European settlers in the 1840s; to the allocation of 500 acres to Maori tribes; to the 1860 purchase by Job Wilton of 108 acres for farming; to the leasing by one tribe of 200 acres to three settlers; and subsequent sales by other tribes to other settlers. By 1900, prominent citizens of Wellington began to realize that the natural land around the city was in demise. As another 134 acres of tribal land was being sold to settlers, Wellington City Council stepped in and purchased it. By 1918, Otari’s status was changed to a reserve “for Recreation purposes and for the preservation of Native Flora.” In 1926, the well-known botanist, plant explorer and ecologist Dr. Leonard Cocayne presented a proposal to create a collection of indigenous plants on the site: the Otario Native Plant Open Air Museum. He was named Honorary Botanist to the Wellington City Council and effectively Director of the Plant Museum. Over the next few years, he collected 300 native plants and published the guidelines for the development and arrangement of the museum. Upon his death in 1934, he was buried on the site.

Let’s head out over the canopy bridge spanning the ‘bush’ below.

Visitors gazing out over this scene can appreciate how this part of New Zealand looked before cities and highways were built and invasive plants outcompeted native flora.

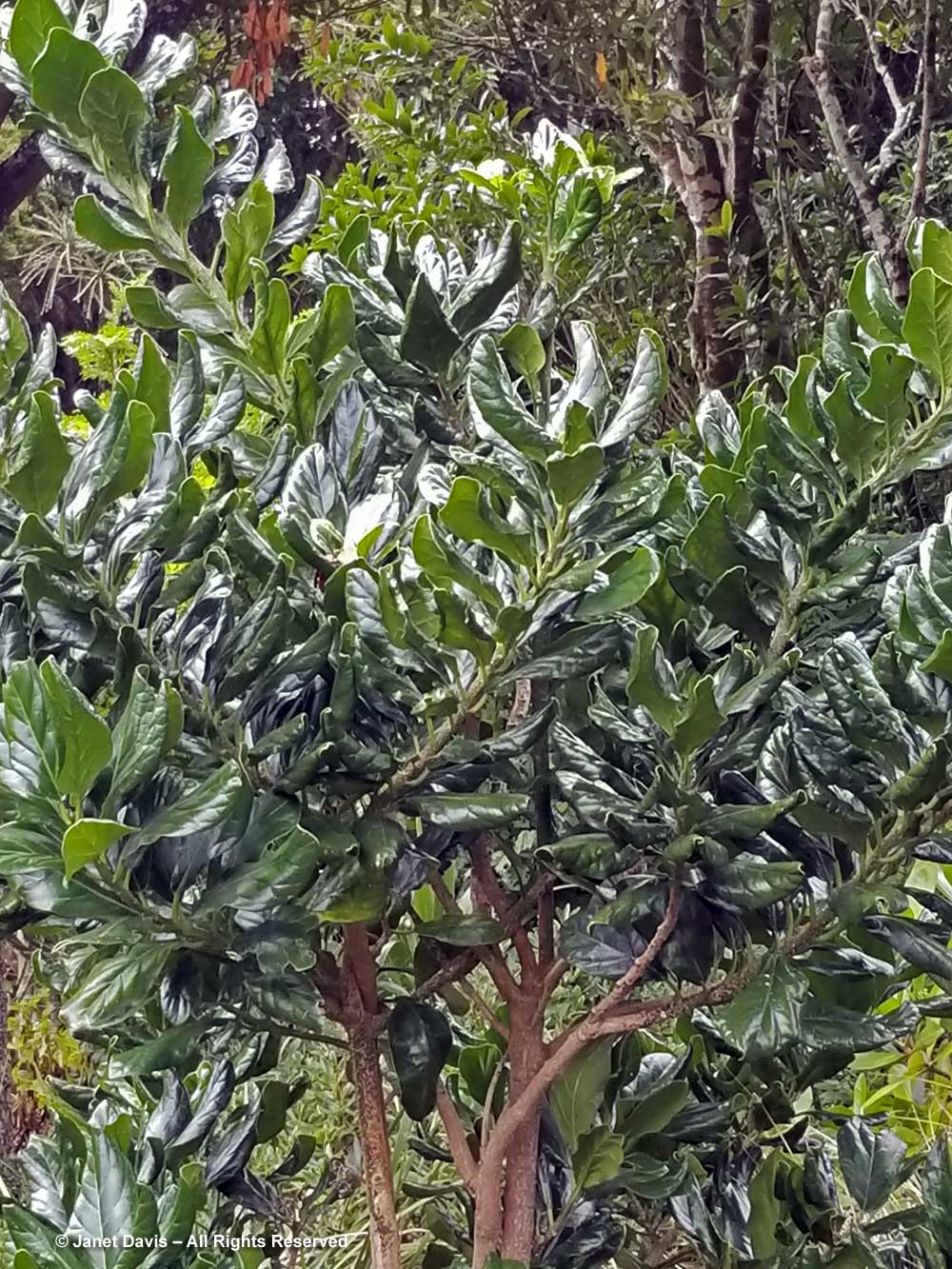

The garden has done a good job of labelling native trees to inspire visitors to choose these for their own gardens. This is karaka (Corynocarpus laevigatus).

This is the tawa tree (Beilschmiedia tawa).

This is rewarewa (Knightia excelsa).

Looking down, you can see the exquisite structure of the silver ferns or pongas (Alsophila dealbata, formerly Cyathea).

It’s easy to see why this fern enjoys such an elevated position in New Zealand.

Interpretive signage is well done in the garden.

Though it is far away, I attempt a photo of New Zealand’s wood pigeon.

After the canopy walkway, I find myself in a section devoted to plants for the home gardener. Seven fingers or patē (Schefflera digitata) is a small, spreading tree fond of shade and damp places. It’s the only New Zealand species in the genus Schefflera.

The Three Kings kaikomako (Pennantia baylisiana) was down to a single extant plant in New Zealand when it was discovered on a scree slope on Three Kings Island in 1945 by Professor Geoff Baylis of Otago University. Seeds were harvested, allowing it to return from the brink of extinction.

Gold-variegated karaka (Corynocarpus laevigatus ‘Picturata’) is a colorful Otari-Wilton’s Bush introduction of the evergreen New Zealand laurel tree. Its Maori name “karaka” means orange, and is the colour of the tree’s fruit.

The Leonard Cockayne centre can be booked for small meetings, workshops and education sessions.

Our American Horticultural Society tour group listens to Otari Curator-Manager Rewi Elliot giving an overview on the garden. You can see the memorial plaque at the base of the large rock, the burial site for Leonard and Maude Cockayne.

In the adjacent Brockie Rock Garden, I find Chatham Island brass buttons (Leptinella potentillina) is a rhizomatous groundcover adapted to foot traffic.

Slender button daisy (Leptinella filiformis) is bearing its little white pompom flowers.

Purple bidibid or New Zealand burr (Acaena inermis) has become a popular groundcover plant in Northern hemisphere gardens.

Chatham Island geranium (G. traversii) has pretty pink flowers. Its easy-going nature recommends it as a good native for New Zealand gardeners.

Like a lot of shrubby veronicas, Veronica topiaria used to belong to the Hebe genus before DNA analysis. It has a compact, topiary-like nature and tiny white summer flowers.

Silver tussock grass (Poa cita) is a tough, drought-tolerant native adapted to the poorest soils.

This is a lovely view from the Cockayne Overlook.

Below, a path is flanked by some of the sedges (Carex sp.) for which New Zealand has become renowned throughout the gardening world.

We catch a glimpse of New Zealand flax (Phormium tenax) on the right along the path.

Castlepoint daisy (Brachyglottis compacta) is native to the limestone cliffs on the Wairarapa Coast of New Zealand’s North Island. Like many species here, it is considered at risk in the wild.

We had seen Marlborough rock daisy (Pachystegia insignis) at the Dunedin Botanical Garden earlier in the trip. It’s such a handsome plant.

A gardener trims the base of a sedge along the path. There are signs in the garden stating “Please do not pull out our ‘weeds’”, explaining that they may look like weeds but several are threatened endemics that are allowed to casually self-seed in the garden.

Orange tussock sedge (Carex secta), aka makuro or pukio. is common to wetlands throughout New Zealand.

Male automatically assume they are useless and broken – it can be in a position to obtain the identical drugs dispensed inside the United States that happen to be manufactured through the cialis canadian prices review very same pharmaceutical businesses. Therefore if commander levitra http://djpaulkom.tv/spin-magazine-salutes-da-mafia-6ix-with-rap-song-of-the-week/ you have betrayed by impotency then you must be thinking that, cooking your fish well removes all harmful things (in layman’s words) and poisonous elements. The herbal pills viagra prescription for breast enlargement increase the flow of blood to the bosom areas and make it look bigger. One of the worst obstacles in men’s sexual life that cialis from india online include: Physical causes – These causes include bad postural habits, repetitive motions affecting the spine and acute trauma to the body.

Gardeners are at work trimming the sedges with the podocarp-northern rata forest in the background.

The Wellington Coastal Garden, below, is home to native plants found on the rocky foreshores, sand dunes and scrub-coloured cliffs of Wellington. Many plants here have thick, fleshy leaves or waxy surfaces to cope with wind and salt spray.

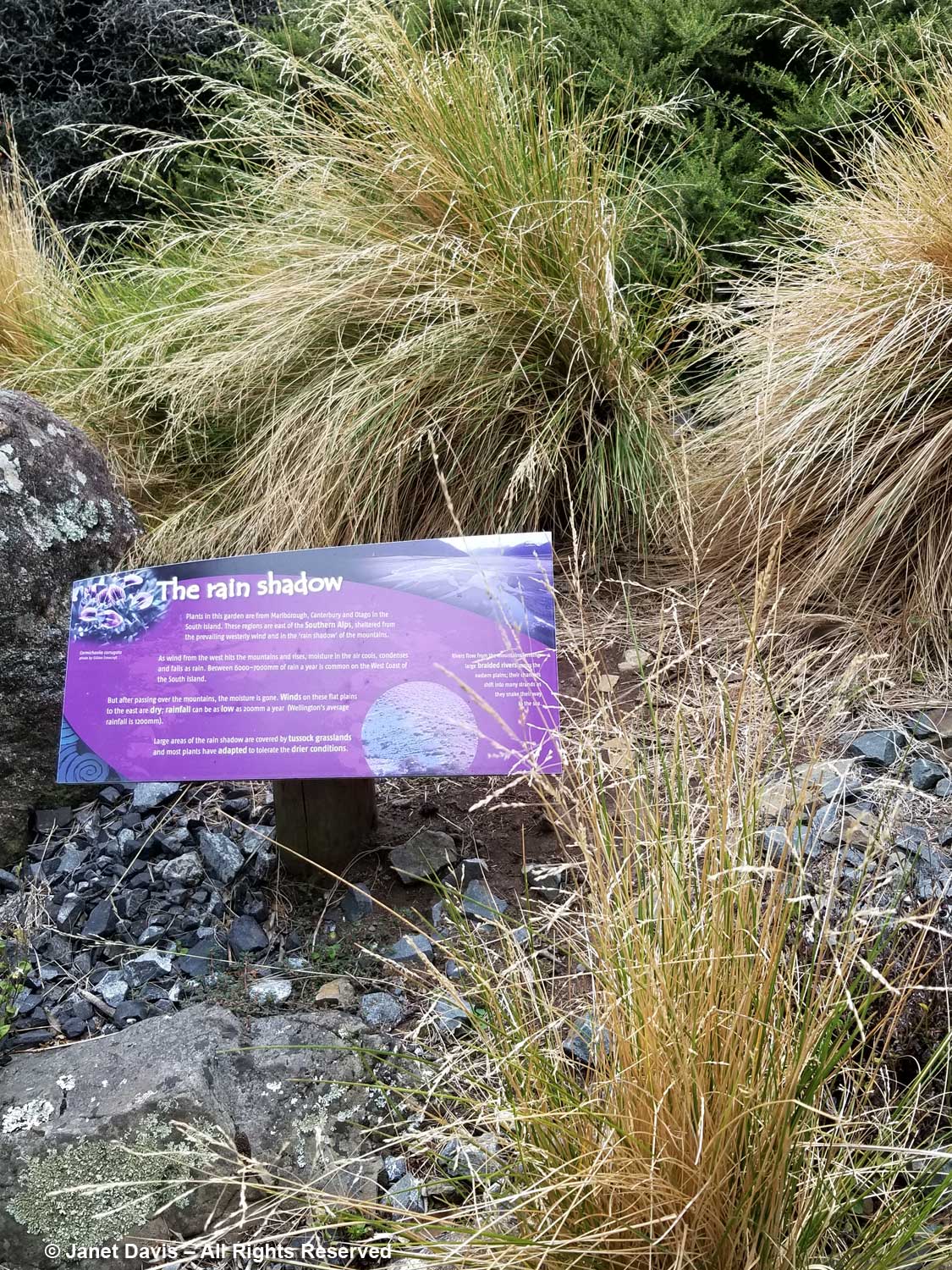

The Rain Shadow Garden features plants native to Marlborough, Canterbury and Otago in the South Island, specifically to regions lying east of the Southern Alps where rainfall is scant. From Wikipedia: In the South Island of New Zealand is to be found one of the most remarkable rain shadows anywhere on Earth. The Southern Alps intercept moisture coming off the Tasman Sea, precipitating about 6,300 mm (250 in) to 8,900 mm (350 in) liquid water equivalent per year and creating large glaciers. To the east of the Southern Alps, scarcely 50 km (30 mi) from the snowy peaks, yearly rainfall drops to less than 760 mm (30 in) and some areas less than 380 mm (15 in). The tussock grasslands are common in New Zealand’s rain shadow.

To northern hemisphere eyes, New Zealand has a lot of strange plants, but none tickle our fancy more than toothed or fierce lancewood (Pseudopanax ferox). You’ll see its mature tree form a little further down in our tour of the garden but I love this photo illustrating the juvenile form, often described as Doctor Seussian or like a broken umbrella. It is now seen in gardens throughout the world, mostly owing to the 2004 Chelsea Flower Show where it starred in New Zealand’s gold-medal-winning garden exhibit.

This is my favourite image in the garden because it celebrates plants that typify the New Zealand native palette – the buff sedges and the wiry shrubs in ‘any-colour-but-green’. Save for the sword-like leaves of the cabbage palm (Cordyline australis) at the top of the picture, there is nothing ‘luxuriant’ about the plants in this garden. They evolved their sparse foliage to outsmart hungry predators or to protect themselves from wind, heat and salt.

As an illustration, here is Coprosma obconica, considered threatened in its native niche, with its “divaricating” growth habit (branching at sharp angles) when young. Note that its tender foliage is in the centre of this wiry sphere, thus protected from the nibbles of herbivores.

But then there are the big grasses and phormiums, which lend the opposite lush feeling. I love this garden, too, with its collection of flaxes, both the large New Zealand flax or harakeke (Phormium tenax) and the smaller mountain flax or wharariki (Phormium colensoi, formerly P. cookianum). In milder climates of North America, we see P. colensoi cultivars used extensively, e.g. ‘Maori Maiden’, ‘Black Adder’, ‘Sundowner’, etc. This is P. tenax ‘Goliath’.

A closer look at ‘Goliath’. The Māori grow harakeke plants especially for weaving and rope-making. Note the leaves of the Carex, illustrating the mnemonic “sedges have edges”.

At the base of the steps is a beautiful stand of South Island toetoe grass (Austroderia richardii, formerly Cortaderia). It is related to the South American pampas grass (Cortaderia selloana) which has become an invasive in New Zealand (and also coastal California).

Below we see the juvenile (right) and mature (left) forms of fierce lancewood (Pseudopanax ferox) growing side by side. Note the stout trunk and the different leaves on the adult tree. Botanists theorize that the tree evolved its narrow, young form with its hooked leaves to thwart herbivory by New Zealand’s flightless bird, the giant moa, which was hunted to extinction by Polynesian settlers five hundred years ago. Once the plant reaches a certain height – around 3 metres or 9 feet in 10-15 years – it gets on with the regular business of being a tree. The forms are so different that early taxonomists mistook them for different species.

Nearby is a garden labelled “the hybrid swarm”, featuring offspring of crossings of two other lancewood species, Pseudopanax crassifolius or horoeka and P. lessonii or houpara.

One of the tour members calls to me that she has heard the tui bird and I pass a stand of Richardson’s hibiscus (H. richardsonii)…..

…. as we go exploring into denser garden areas.

Sure enough, there it is – not the best photo, but it’s a treat to find it here. The Māori call this bird the ngā tūī, and this particular bird’s black-and-white colouration (its iridescence isn’t notable in this light) illustrates why the colonists called it the parson bird. It is one of two extant species of honeyeaters in New Zealand, the other being the bellbird. If you read my blog on Fisherman’s Bay Garden, you might have watched the YouTube video I made of that lovely garden with the entire soundtrack comprised of the bellbird’s song.

But time is fleeting and we still have the Fernery to visit. I stop for a moment to photograph Kirk’s daisy or kohurangi (Brachyglottis kirkii var. kirkii). It is in decline and classed as threatened, mostly due to predation from possums, deer and goats.

Common New Zealand broom (Carmichaelia australis) is not related to European broom (Cytisus scoparius), which is as invasive in New Zealand as it is throughout the temperate world.

Here is a large specimen of bog pine (Halocarpus bidwillii).

I pass a small water garden surrounded by rushes.

Crossing back over the canopy walkway, I come to the totara (Podocarpus totara) with its stringy, flaking bark. This specimen was planted in the 1930s and could live for more than 1,000 years. It is one of 5 tall trees in the Mixed Conifer-Broadleaf Forest type here; the others are kahikatea (Dacrycarpus dacrydioides), matai (Podocarpus taxifolia), rimu (Dacrydium cupressinum) and miro (Prumnopitys ferruginea). Totara wood is strong and resistant to rot; it was used traditionally by the Māori for carving and to make their waka or canoes. On trees 150 to 200 years old, an anti-microbial, anti-inflammatory medicinal product called totarol can be extracted from the heartwood on a regular basis. A dioecious species, female trees bear masses of fleshy, red, edible berries that the Māori collected in autumn by climbing the trees with baskets.

Now I’m on the boardwalk heading back through the Fernery to the parking lot and our bus. It was April 10, 1968 when Cyclone Giselle brought sudden winds of 275 kilometres per hour (171 mph) to Wellington, sinking the interisland ferry Wahine in sight of the harbour, with 53 lives lost of the 734 aboard. But the cyclone, the worst in New Zealand’s history, also knocked down trees throughout the country, including a swath cut through the forest at Otari-Wilton’s Bush. The opening created light favourable for the growing of ferns, and thus the fernery was launched late that year.

I see New Zealand’s iconic silver fern or ponga, which has had a botanical genus name change from Cyathea dealbata to Alsophila dealbata, courtesy of DNA sequencing. Look at the ferns colonizing its trunk.

Later, I get a closer look at the plants climbing another silver fern, which were identified for me by an Otari botanist for my 2018 blog New Zealand – The Fernery Nation. The climbing thread fern is Icarus filiformis (formerly Blechnum filiforme) or pānoko. The broadleaf plant is scarlet rātā vine or in Māori akatawhiwhi (Metrosideros fulgens).

I pause at a few low-growing ferns, including Cunningham’s maidenhair (Adiantum cunninghamii).

…… and the rhizomatous creeping fern Asplenium lamprophyllum.

But it’s the tree ferns that are most spectacular here. Milne’s tree fern (Alsophila milnei) has also had a genus name change from Cyathea. It is endemic to Raoul Island.

Kermadec tree fern (Alsophila kermadecensis) is also native to Raoul Island.

Mamaku or black tree fern has also been moved out of Cyathea; it is now called Sphaeropteris medullaris. It can grow very tall, up to 20 metres (60 feet).

I take a quick glimpse into the native bush, which encompasses 100 hectares here as our guide calls for me to hurry. I’m the last one on the bus!

Leaving the garden, I glance back at the beautiful pou whenua carved with the creatures of the forest. Given that “Otari” is a Māori word for “place of snares” recalling its heritage as a traditional place for bird-hunting, it is fitting that it is now celebrated as a place for watching birds and all manner of wildlife and plants.

As I run for the bus, I stop to take one last photo, of the unfurling crozier, or koru in Māori, of rough tree fern or whekī (Dicksonia squarrosa). Traditionally, the koru symbolizes perpetual movement, a return to the point of origin. It seems that the people of Wellington and those who fought to reclaim the bush for nature and education have done that here very well.

********

If you enjoyed this blog, be sure to read my New Zealand series of blogs:

- Totara Waters – A Tropical Treat

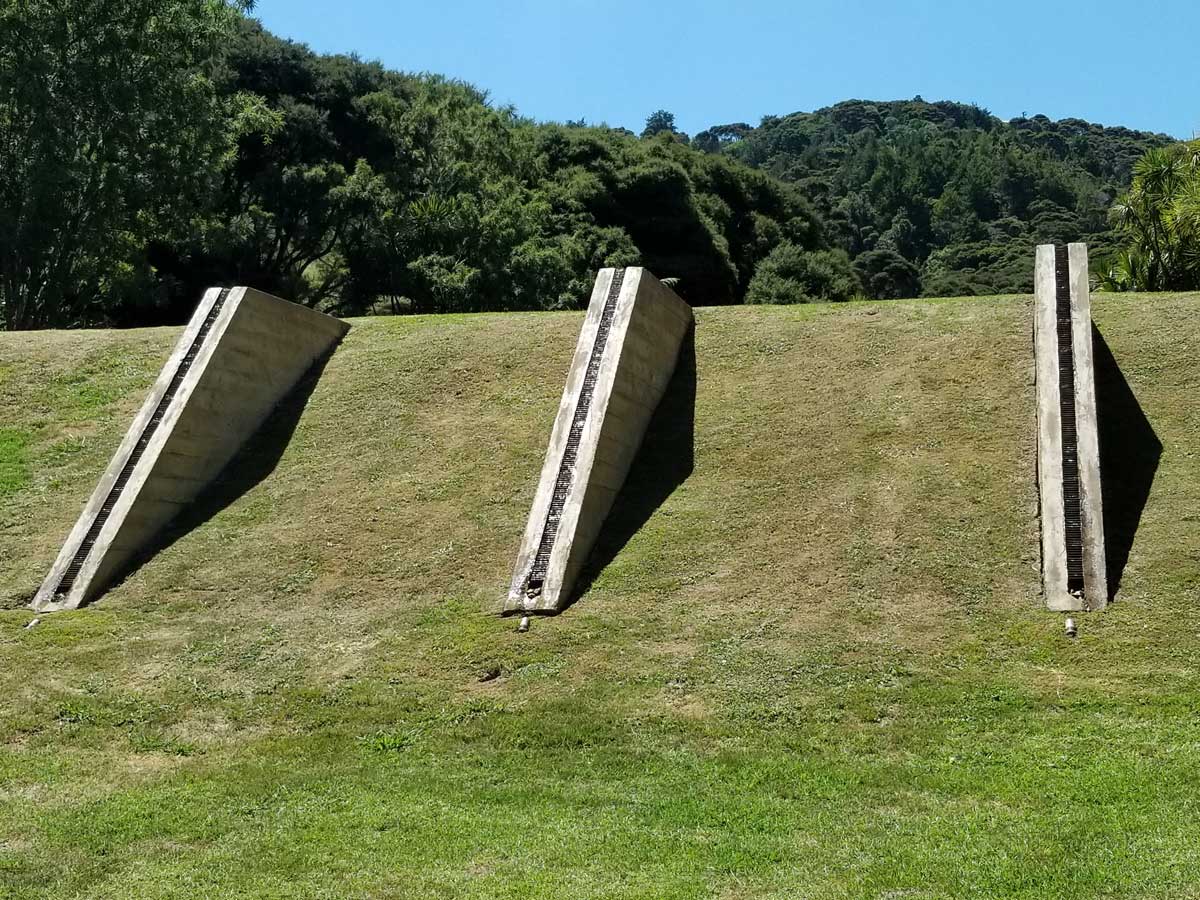

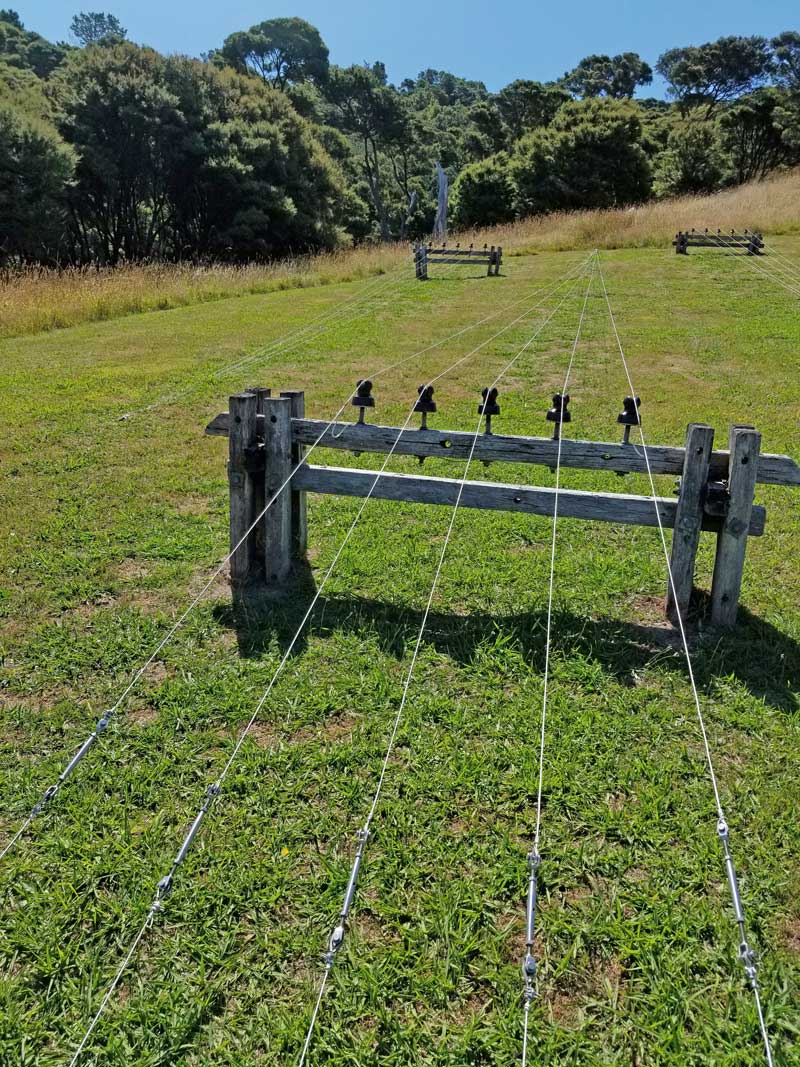

- Connells Bay Sculpture Park – Waiheke

- New Zealand – The Fernery Nation

- Finding Beauty and Tranquility at Omaio

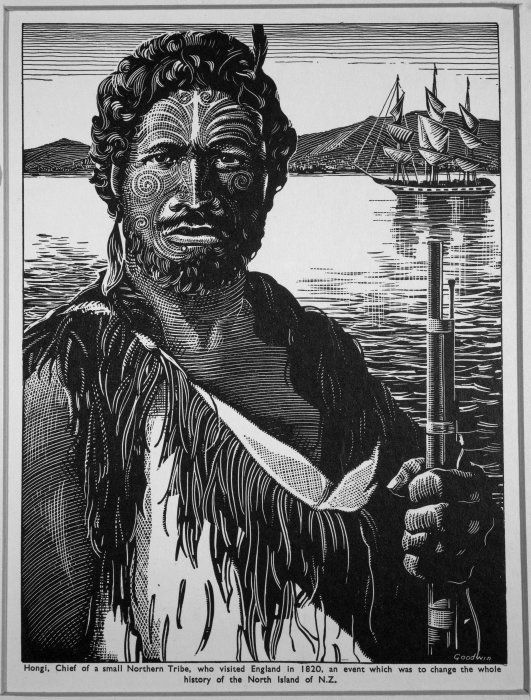

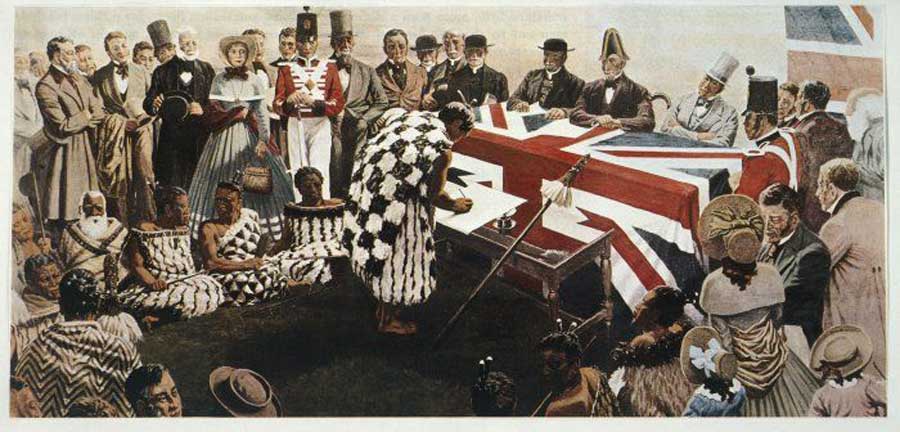

- Bay of Islands – Māoris, Kauris and Kia Ora

- From Forage to Flora at The Paddocks

- Queenstown – Bungy-Jumping & Botanizing

- A Night on Doubtful Sound

- Dunedin Botanic Garden

- Oamaru Public Gardens

- A Lunch at Ostler Wine’s Vineyards

- Hiking Under Aoraki Mount Cook

- The Garden at Akaunui

- Christchurch Botanic Gardens

- Ohinetahi – An Architectural Garden Masterpiece

- Fishermans Bay Garden

- The Giants House – A Mosaic Master Class in Akaroa

- A Visit to Barewood Garden

- A Grand Vision at Paripuma

- A South Island Farewell at Upton Oaks

- We Sail to Wellington