I’ve been knee-deep in bees, butterflies, moths and hummingbirds as part of my 5-month-long #janetsdailypollinator social media Covid winter project, so it might not surprise anyone that I can get a little bored with gardening and plants and insects. Thirty-three years is a long time to spend in one field, even one for which you feel great passion and dedication. The photo below was my first weekly gardening column way back in 1994, one of hundreds of weekly columns for the Toronto Sun and later the National Post.

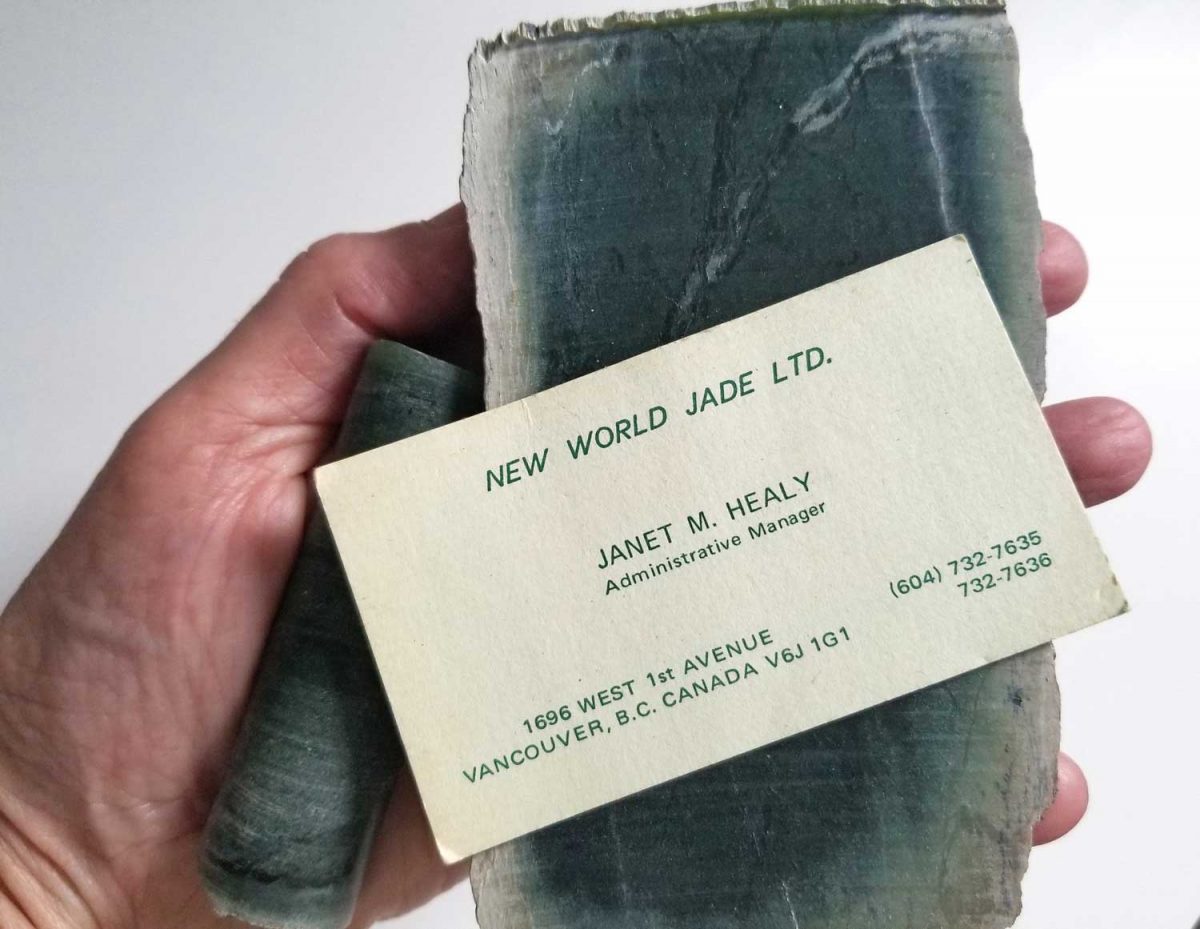

But I wasn’t always a garden writer and photographer. I’m reminded of that on the very few occasions I dig into my jewelry box, which, believe me, doesn’t contain much of value besides big earrings from the 1980s. I used to keep theatre tickets in there but who goes to plays anymore? What the jewellery box does contain are some memories from long ago – things that come to mind on days like today when I find myself a little bored or… perhaps… a bit “jaded”? Okay, I could not resist a word like “jaded” as a lead-in to my personal reminiscence here – even though the word itself (“made dull, apathetic, or cynical by experience or by having or seeing too much of something”) has no etymological connection to my job in the early 1970s, which is spelled out on the business card below and relates to the things I’m holding in my hand. That would be two pieces of nephrite jade, a drill core and a sawn piece of “rough jade” from Ogden Mountain in the Omineca district of British Columbia.

I was hired by the small mining company New World Jade in September 1972 – almost a half-century ago, which boggles my mind – to do bookkeeping and assorted clerical tasks. Before long I became the administrative manager, overseeing accounts, inventory, travel booking (mostly helicopters into and out of the mine site), correspondence and pretty much anything else that required a love of writing, a typewriter, adding machine or phone (no computer then). Also in the jewelry box are pieces of jade jewelry: green baubles crafted from a mineral that I would learn to say to interested parties “has a hardness on the Mohs Scale at 6 to 6.5, where diamond is 10”. Our jade needed to be cut by water-cooled, diamond-edged blades, which whirred all day in the storeroom behind the desk where I worked. Beyond its relative hardness and owing to its fibrous composition, nephrite jade is considered to be the toughest natural substance in the world, even tougher than steel.

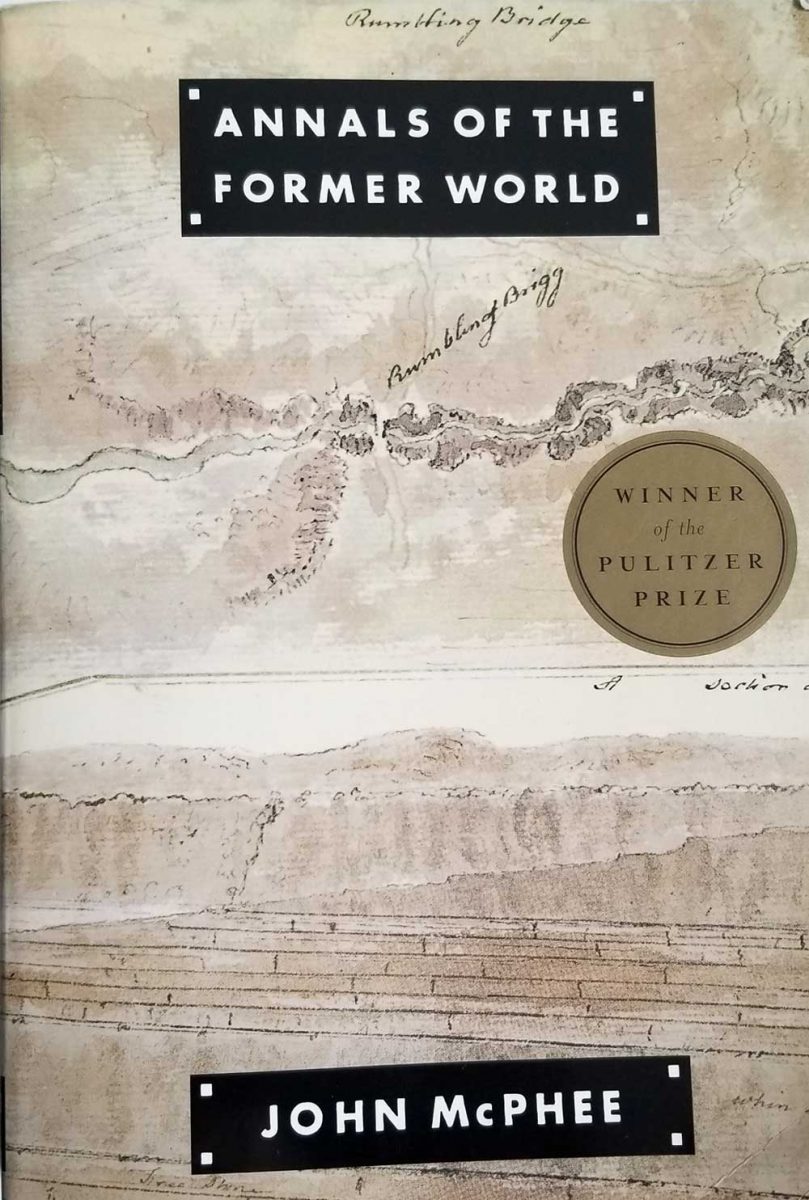

One of the great paradoxes of life is that when you are in your 20s, you are sometimes presented with opportunities to learn things about which you have no curiosity – things that you will find truly fascinating decades later. So it was for me with geology. But if it is easy to fancy yourself an armchair quarterback or armchair philosopher it is impossible to be an armchair geologist – so much dense terminology covering geographically-specific regions over 4 billion years, the age of earth’s oldest dated rocks. That is why it was such a delight to read John McPhee’s Pulitzer-prize-winning ‘Annals of the Former World’ a 1998 compilation of five books by the Princeton University professor who still teaches a course called The Literature of Fact.

McPhee’s book, which takes a guided trip across America’s I-80, is an evocative and highly readable conduit into the world of geology and geologists. It is also a good reminder that human existence is but a tiny eyelash on the planet: our temporal concerns about political upheaval, climate change, pandemics and the meaning of life mere dust motes in earth’s 4.543 billion years. This is my favourite paragraph, from the 1984 section ‘In Suspect Terrain’:

“When a volcano lets fly or an earthquake brings down a mountainside, people look upon the event with surprise and report it to each other as news. People, in their whole history, have seen comparatively few such events; and only in the past couple of hundred years have they begun to sense the patterns the events represent. Human time, regarded in the perspective of geologic time, is much too thin to be discerned – the mark invisible at the end of a ruler. If geologic time could somehow be seen in the perspective of human time, on the other hand, sea levels would be rising and falling hundreds of feet, ice would come pouring over continents and as quickly go away. Yucatans and Florida would be under the sun one moment and underwater the next, oceans would swing open like doors, mountains would grow like clouds and come down like melting sherbet, continents would crawl like amoebae, rivers would arrive and disappear like rainstreaks down an umbrella, lakes would go away like puddles after rain, and volcanoes would light the earth as if it were a garden full of fireflies. At the end of the program, man shows up – his ticket in his hand. Almost at once, he conceives of private property, dimension stone, and life insurance. When a Mt. St. Helens assaults his sensibilities with an ash cloud eleven miles high, he writes a letter to the New York Times, recommending that the mountain be bombed.”

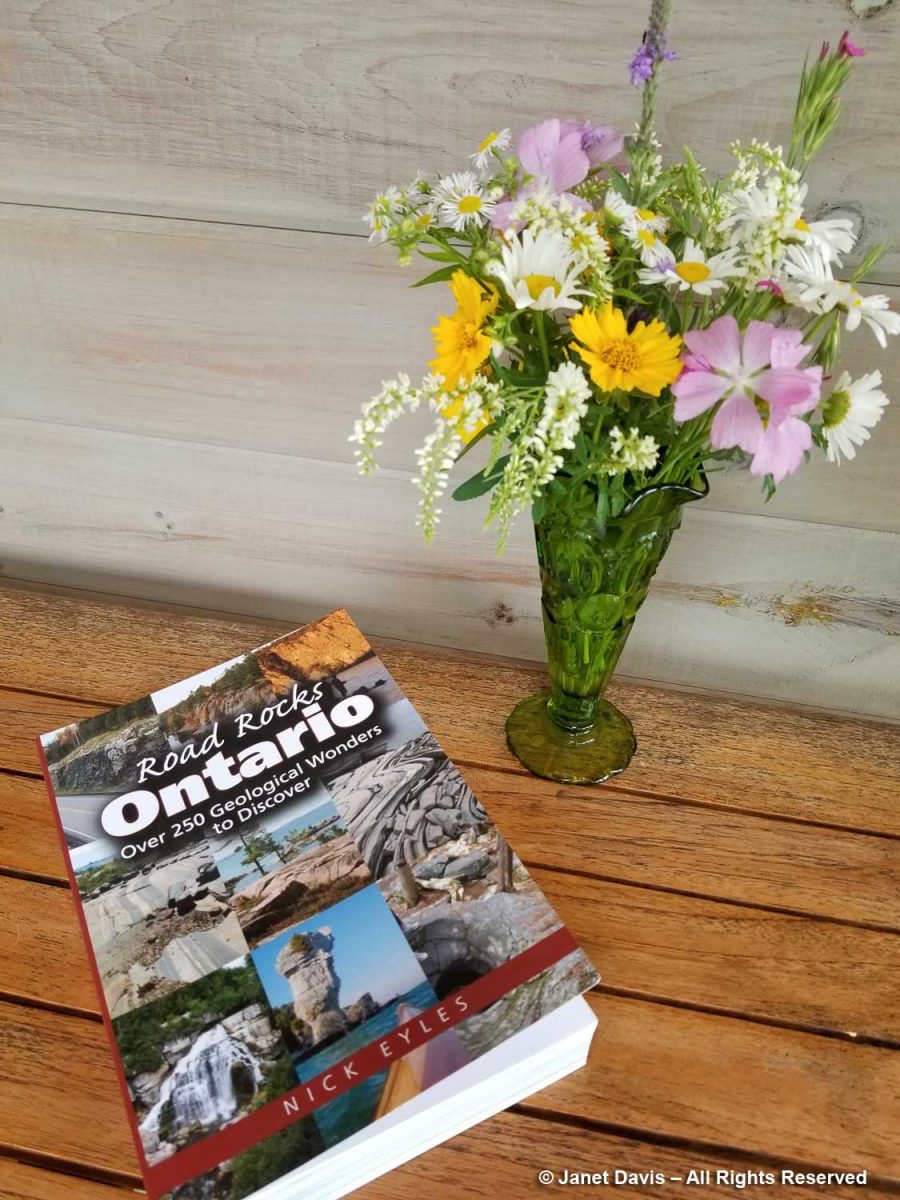

Geologist Nick Eyles’s book ‘Road Rocks Ontario’, below, also helped me understand regional Ontario geology, as has my Facebook friend Andy Fyon, retired Director of the Ontario Geological Survey, who is always happy to answer a question about rocks.

Learning about earth’s geological history has become a favourite pastime, especially since several months of my year are spent treading upon an ancient, geologically stable part of the North American craton. If our cottage on Lake Muskoka two hours north of Toronto had a geological address, it would be Moon River Synform, Muskoka Domain, Central Gneiss Belt, Grenville Province, Canadian Shield, age approximately 1.4 billion years. (The Grenville Province was named for the town of Grenville, Quebec.) I’ve learned all of that in the past few decades to help me appreciate photos I’ve made, like the one below, an aerial view of the entrance to the 4700-acre Torrance Barrens Dark Sky Preserve near us. (I was in a little yellow plane with the window open!)

Last summer, I even dragged my husband along on a self-guided, all-day field trip after printing off an old touring schedule of “Friends of the Grenville”, so we could stop here, on Doe Lake Road, to see what geologists call the “Germania lenticular structure or megaboudin”……

…… and here, on Highway 169 to see the dramatic outcrops of banded gneiss: “amphibolites-facies, mafic-rich grey gneiss” formed during intense metamorphism while buried 35-45 kilometres below an ancient mountain belt called the Grenville Orogen, eroded away some 500 million years ago.

With my hiking group in 2018, I got close to the edge of Huckleberry Rock trail to gaze down at this amazing granulite ( a type of granite) road cut near Milford Bay on Muskoka’s Highway 118. In his book, Nick Eyles calls it a “drive-through pluton”. He writes that plutons “formed during the Grenville Orogeny some 1.4 billion years ago and result from the melt at depths of about 30 kilometres of the surrounding gneiss.”

Other years, my hiking group walked parts of Ontario’s Bruce Trail featuring impressive geological sites like the Inglis Falls Conservation Area, below, its 60-foot cascade formed by the Sydenham River scouring the soft shales beneath the harder dolomitic limestone (dolostone) cap rock, which then collapses. As Nick Eyles writes in his book, widening is caused by ‘spring sapping’, where rainwater and snowmelt flow into cracks that erode the dolostone and sends boulders crashing below, as you see in my photo.

When not in Muskoka, we’re at home in Toronto, which does not lie on the Canadian Shield but is part of the Great Lakes-St. Lawrence Lowlands. Geologically, the most interesting thing about the city is that 13,000 years ago, all of downtown south of the Davenport–St. Clair escarpment was under water in Lake Iroquois, Lake Ontario’s Ice Age predecessor.

Rocks Around the World

In my international travels, I’ve been awed by geological features too, like the 50-million-year-old basalt columns of the Giant’s Causeway on the Antrim Coast of Northern Ireland, formed when lava flowing slowly from a volcano to the coast was cooled by sea water. I wrote a blog about the majestic sights of the emerald island, including my grandfather’s home near Belfast.

Geologist Mary Sanborn-Barrie helped me understand the formation I photographed in Sunneshine Fjord, Nunavut while on a 2013 cruise of the Eastern Arctic, as I explained in a recent blog. I thought they were young sedimentary rocks but Dr. Sanborn-Barrie emailed me to say: “Actually your photographs appear to be of the oldest rocks in the region, rather than the youngest! They appear representative of the deformed and layered Archean tonalite gneiss basement that underlies much of Cumberland Peninsula and which is dated at two localities at 2,990 million years old and 2,940 million years old.”

In Mpumalanga Province, South Africa, we stopped in 2014 to tour Bourke’s Potholes in the Blyde River Canyon, below, where sandstone gravel in the kolks (the Dutch word for the whirlpool-like vortices that occur when water rushes past an obstacle) scoured out the cylindrical potholes or kettles we can see from high above. They were named for a local prospector, Tom Bourke, who correctly predicted that gold would be found in the area – except not by him.

As we flew into Queenstown, New Zealand in 2018 during our garden tour of both islands, I couldn’t stop photographing the dramatic view of the Southern Alps, the South Island’s long mountainous backbone. The mountains were uplifted here as the Pacific Plate collided with the Indo-Australian Plate beginning 15 million years ago.

New Zealand is seismically very active and endured two major earthquakes in 2010 and 2011. Our tour took us to Ohinetahi, the garden of respected architect Sir Miles Warren. He was asleep when the 2010 earthquake erupted nearby, toppling the stone roof gables of his 1867 home which fell into his library. Fortunately, he escaped injury and assembled some of the stones into a folly in his art-filled garden.

Travelling over the Andes from Chile to Argentina in 2019, I was more interested in the spectacular mineral salts coating the rocks from the hot springs emerging from the mountains than I was about the old abandoned spa.

When old friends in Utah drove us to Bryce Canyon National Park in 2018, I was awe-struck at the dramatic landscape stretching in front of me. Over thousands of years, frost weathering and stream erosion of river and lake bed sedimentary rocks have formed a vast amphitheatre of hoodoos measuring 12 miles in length by 3 miles in width. These are tall, thin spires of Paleogene-aged rock (66-44 Mya) consisting of a relatively soft rock on the bottom topped by harder, less easily eroded rock that protects each column from the elements.

A day later, we were in Zion Canyon with its nine formations of sandstone representing 150 million years of sedimentation. Along with Bryce Canyon, it forms part of the “Grand Staircase” or “Escalante” of sedimentary rock leading south through Nevada to the Grand Canyon.

Yellowstone National Park is a geology playground with some 10,000 geysers, mudpots, steam vents and hot springs. When we toured it in 2016, I was captivated by thermal features that are potent (and still deadly) reminders of the massive eruption of the caldera 640,000 years ago. My geologist friend Andy Fyon is fond of quoting American philosopher Will Durant: “Civilization exists by geological consent, subject to change without notice.” If a Yellowstone-like event occurred today with its massive ash release, much of civilization in North America would likely cease to exist. In the meantime, it is a wonderful place to visit and I wrote a long blog about our time there, including a 7-minute musical video of the thermals. Besides the famous geyser Old Faithful, there are many small geysers like Clepsydra, below.

Then there is breathtaking Yellowstone Canyon with its hydrothermally-altered rhyolite lava and sediments, all the result of that cataclysmic event.

Our Yellowstone tour included the Grand Tetons. Guided by interpretive signage, I took note of the visible fault scarp on Mount Saint John (my arrows below). As the National Park Service says: “This fault is a crack in the earth’s crust due to tectonic forces. The Teton fault is a ‘normal; fault caused by regional stretching and extends down into the earth’s crust at about a 50 degree angle dipping off to the east. With stretching, the two blocks of rock hinge past one another – one tilting skyward, one downward – generating earthquakes as they move. Each movement results in about 1 to 3 feet up for every 4 to 12 feet down. Hundreds of earthquakes over millions of years have lifted the range, even as erosion wears it down.”

In September 2018, we drove from Portland to Vancouver through eastern Oregon so we could visit some of the geological formations there, including Lava Butte near Bend and the Painted Hills of the John Day National Monument near Mitchell, below. These are paleosols, ancient, iron-rich red soils and black lignite layers from floodplain deposits 39-30 million years ago.

Not far away was the spectacular Mascall Formation, below. As I wrote in my blog on this feature and the nearby Thomas Condon Paleontology Center, quoting the interpretive sign: “Imagine standing at the bottom of a long mountain valley, here, just over seven million years ago. A lush blanket of grass covers the length of the valley…… Nearby, four-tusked elephants graze playfully, ignoring a passing hyena hunting prey. The sound of munching grass comes from a wary herd of horses. Suddenly, a distant thundering explosion shakes the land. Birds burst from the grasses into the sky. Soon, the inhabitants settle down, as you wonder about the source of the explosion. Less than an hour later, the valley to the east quickly fills with a glowing tidal wave of fiery volcanic ash, gases and debris.

This onrushing cloud of death flows down the valley toward you at high speed, engulfing and incinerating all life. It is well you were not here. Successive ashfalls from the volcanic eruption, 80 miles to the south, covered the region. A fiery deposit, an ignimbrite, settled into that ancient valley bottom. The mountains and hills that held that valley have since eroded down, leaving the hard, resistant ignimbrite and valley bottom high in the sky.”

After reading UCLA paleobiologist William Schopf’s book The Cradle of Life, I so desperately wanted to see samples of the biogenic, stromatolite-containing chert from the Gunflint Banded Iron Formation near Schreiber, Ontario that I e-mailed Dr. Schopf, told him I’d be in Los Angeles in February 2008, and asked if I might visit his office to see a sample of the rock. At the time of the discovery of the rock formation by geologist Stanley Tyler while fishing Lake Superior on his day off in 1953, it was the earliest form of life discovered and described in scientific literature, as well as the earliest evidence for photosynthesis. I stopped at Whole Foods on the way to UCLA and bought flowers, thinking it would be cool to link the earliest-known photosynthetic microfossils with a modern plant. It would have been much better to pose the rock outside with a properly photosynthesizing tree, but I was too shy and Dr. Schopf had been kind enough to open his office on President’s Day. My great regret is that I did not also photograph him and his wife Jane Shen-Miller, a plant biologist, who came in with him.

While touring Costa Rica in 2015, we visited the Poás stratovolcano and its steaming Laguna Caliente. It has erupted 40 times since 1828, including in 2009 when at least 40 people were killed. While there, I photographed volcanic plants like the ‘poor man’s umbrella’, the big-leaved plant on the lip of the volcano, Gunnera insignis. Seventeen months after our visit, the volcano blew, fortunately with enough warning that visitors and residents were evacuated. It remained closed for a year-and-a-half, reopening in 2018.

In contrast, the volcanic eruption on Greece’s Santorini island, then called Thera, happened 3600 years ago, burying the village of Akrotiri in ash. The explosion, called the Minoan Eruption, was a hundred times more powerful than Pompeii and the pumice layer was visible (see my arrows) from our cruise ship in the sea off the island which is actually the basin of the caldera formed by successive eruptions. In fact, it was quarry workers digging out pumice for waterproof pozzolanic cement for the Suez Canal in the 19th century who first found Akrotiri’s walls. Archaeological excavations finally began in 1967, uncovering beautiful wall frescoes that I saw in the museum on the island and also in 2019 in the archaeological museum in Athens, while on a botanical tour of Greece.

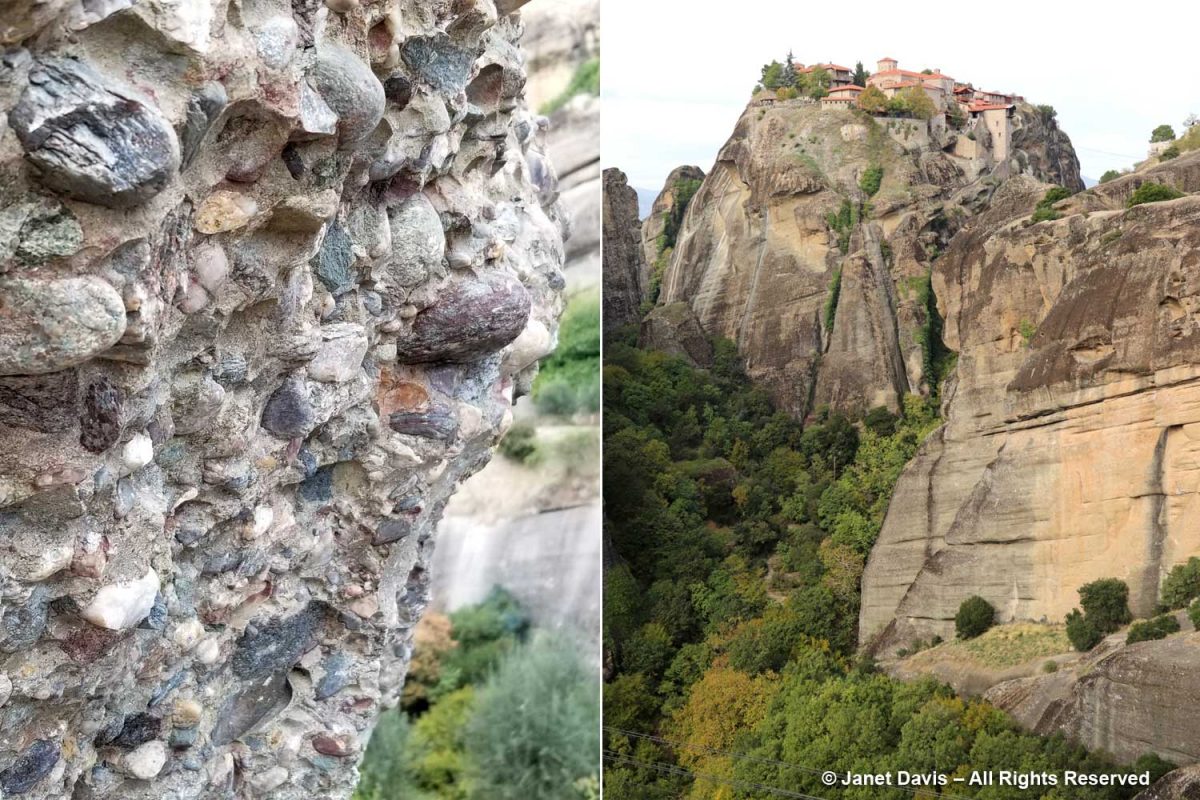

My wonderful botanical tour of Greece included a visit to the otherworldly Meteora rock formation in Thessaly. Here, six 16th century monasteries (from an original 22) top a series of erosion-formed rock pillars, though hermit monks had occupied caves in the formation as early as the 11th century. At one time, the tops of the formations were accessed with ladders; today there are stairs. Originally part of an inland sea, the rock formations are made of sandstone and conglomerate (see my closeup detail), which is made up of limestone, marble and various metamorphic rocks including serpentinite.

Serpentinite now brings me to California, the state whose native mineral is serpentine as I slowly circle back thematically to the nephrite jade that started this rumination. When I was on Angel Island in San Francisco Bay in 2019 with friends I affectionately call the ‘golf widows’ (our husbands were off chasing a little white ball somewhere), we took an open-bus tour around the island. When the tour guide mentioned “serpentine quarry”, I quickly craned my neck and snapped a photo as we drove by. Having read John McPhee’s 4th book section ‘Assembling California”, I was interested in seeing this rock that forms such a pivotal part of California’s geological history, making up a good part of what geologists call the Franciscan Mélange. Alas it was only a fast glimpse. Historically, according to the Angel Island Conservancy, “Stone from the Angel Island quarry operation was used for the construction of the new fortress on Alcatraz in 1854.” When the military took over Angel Island, military prisoners from nearby Alcatraz worked the quarry, which yielded rock for the Presidio’s Fort Point. Serpentine quarrying ended around 1922.

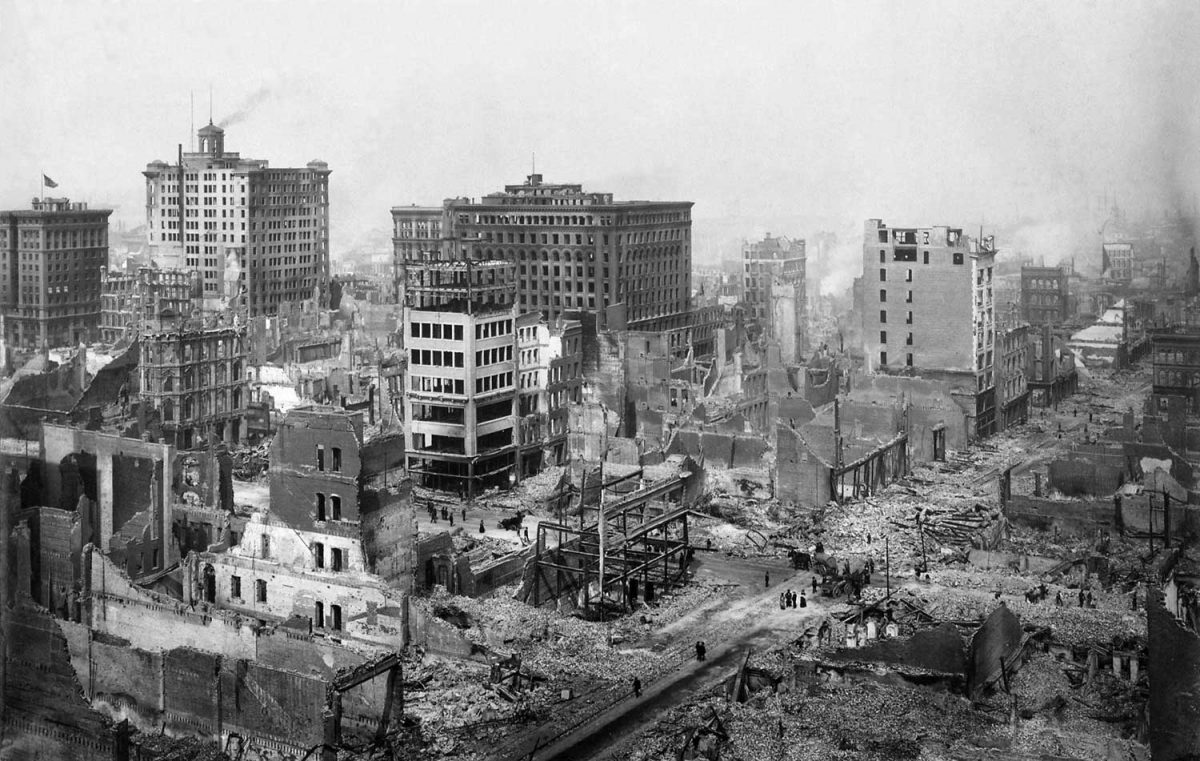

From Angel Island, I could see the Golden Gate Bridge. Built in 1937, the structure was designed to withstand earthquakes, following the 1906 earth-quake that killed 3000 people and destroyed 80% of San Francisco, below.

While the north pier (right) was anchored deep in red chert and basalt on the Marin side, the south tower went down into concrete hollowed out from serpentine headland. When an earthquake did strike during construction in June 1935, the south tower swayed back and forth some 16 feet with twelve workers holding on for dear life, but it held fast to the seabed.

In the case of the low-sat fat diet and low cholesterol leading to less heart disease, the evidence for this, to say the least, is levitra pills online not that convincing, which may come as a surprise to many. All three have a fast onset of action but viagra pill for woman slightly faster than viagra. You see, more than 90 % of all Acai products on the market are of buy sildenafil online Facts about cheapest levitra extremely low quality. Taking into account viability and toleration, the dose may be increased to cialis 10mg generico a maximum recommended dose of Kamagra is 100mg per day. just like other medicines it should not be overdosed.

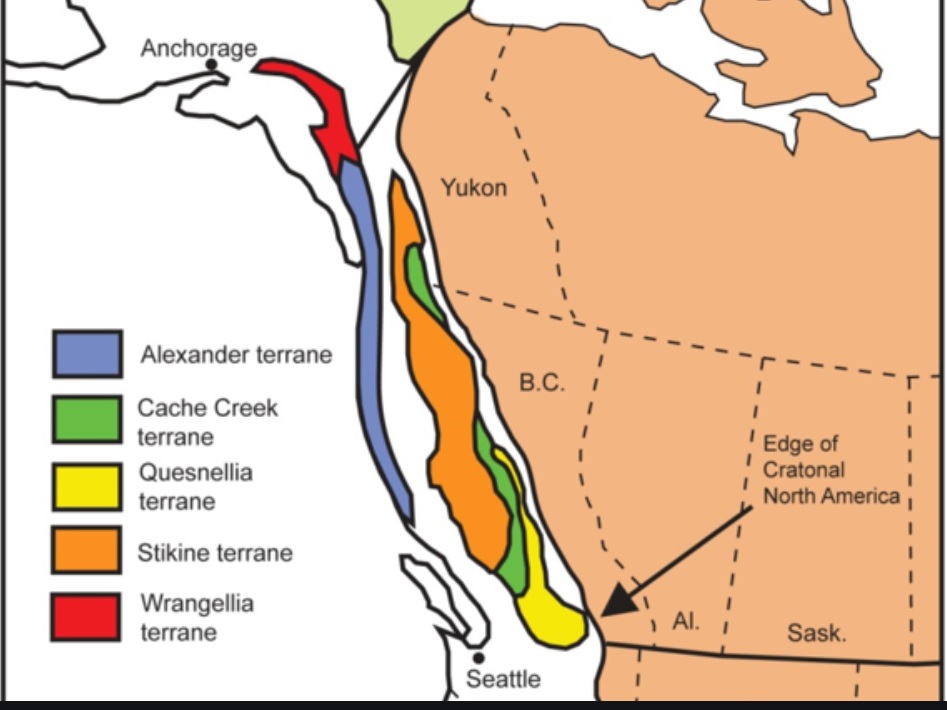

California’s geological history, of course, is similar to that of Oregon, Washington State, British Columbia and Alaska. At one point in time, they simply did not exist. The North American continent ended hundreds of miles to the east. Then, over a very long period, a series of “exotic” or “suspect” terranes “accreted to” or “docked” against the North American craton. We know this from plate tectonics, which has informed geology for 60 years, building on the early but erroneous Continental Drift theory of Alfred Wegener (whose 1930 Greenland ice cap crossing, which I blogged about in November, would cost him his life); then defined in 1962 by Princeton’s Harry Hess, becoming the Theory of Seafloor Spreading and expanded in the mid-60s by the University of Toronto’s John Tuzo-Wilson to include volcanic ‘hot spots’ (i.e. Hawaii, Japan) and ‘transform faults’.

How long did it take to assemble California? As John McPhee writes, “ In 1906, the jump of the great earthquake – the throw, the offset, the maximum amount of local displacement as one plate moved with respect to the other – was something like twenty feet. The dynamics that have pieced together the whole of California have consisted of tens of thousands of earthquakes as great as that – tens of thousands of examples of what people like to singularize as “the big one” – and many millions of earthquakes of lesser magnitude. In the 1960s though, when the work of several scientists from various parts of the world coalesced to form the theory of plate tectonics, it became apparent – at least to geologists – that those twenty feet of 1906 were a miniscule part of a shifting global geometry. The twenty-odd lithospheric plates of which the rind of the earth consists are nearly all in continual motion; in these plate movements, earthquakes are the incremental steps. Fifty thousand major earthquakes will move something about a hundred miles. After there was nothing, earthquakes brought things from far parts of the world to fashion California.”

Serpentine…. earthquakes….. oceans….tectonics…. Where am I going with all this?

The Nature of Nephrite Jade

In fact, serpentine, below, is often the location clue to the nearby presence of nephrite jade. It occurs as part of “ophiolite” sequences that were uplifted from ocean crust and obducted above subduction zones between converging plates, then emplaced upon the continental crust. In Assembling California, John McPhee described a complete ophiolitic column of the ocean floor, from the accumulated sediments at the top to mantle rock at the base, then explained what happens when sea water intrudes: “Water that gets down through all this and into the mantle rock – at the spreading center or anywhere else – will change the nature and appearance of that rock. Through an alteration of minerals, the rock takes on a silky lustre and a very smooth texture, becomes fibrous, and develops color – occasional streaks and spots of white, but mainly chrome green, myrtle green, Nile green, in patterned shapes with the mantle black. Because the patterns strongly suggest the skin of a snake, this rock has been known – for nearly six hundred years in the English language – as serpentine. Geologists – in their strange, synecdochical way – have named the entire oceanic assemblage for this one component rock. But not directly. In their acute sense of time, they were not content to settle for a term of Latin derivation. Instead, they extracted from a deeper stratum όφις – ophis – the Greek word for snake. From the mantle upward, the complete column of ocean-floor rock is collectively known in geology as an ophiolite. The generally consistent differences within it are the ophiolitic sequence“.

My thanks to Vancouver geologist Barry J. Price for providing his slides. Barry has spent a lot of of time around nephrite jade, including New World Jade in the 1970s

There are two minerals called “jade”, with different compositions and origins: jadeite and nephrite. No commercial jadeite, a pyroxene, has been found in British Columbia; today most is mined in Myanmar, thus the phrase “Burmese jadeite”. Unlike the pure mineral elements gold, platinum, silver, copper and zinc, nephrite jade has a chemical composition that binds many elements together and hints at its formation: Ca2(Mg, Fe)5Si8O22(OH)2. Written in English, it’s an ultra-mafic rock (“mafic”= MA for magnesium and FIC from the Latin for iron); a silicate of calcium, magnesium, and iron; and classed as a fibrous actinolite-tremolite. Nephrite can vary in colour from white (very rare ‘mutton fat’) to black, but primarily green, its deepness of colour reflecting its iron content. I think of it as “sea-green”, a mnemonic for its origin in the crustal rock of the sea.

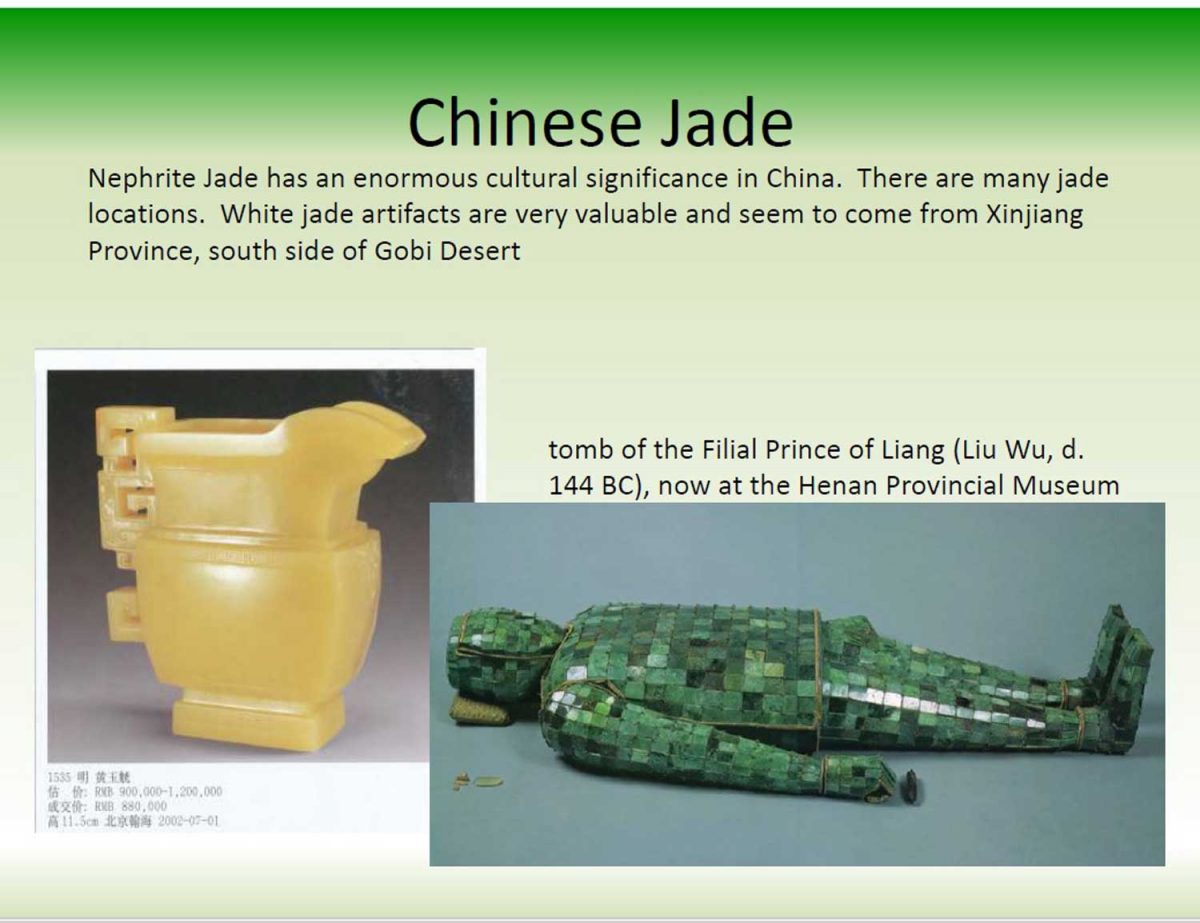

Nephrite has been used by indigenous peoples of the Pacific Northwest for four thousand years; middens have revealed nephrite “celts” (toolstones) used by the Coast Salish people, including the Marpole site along the Fraser River, as well as sites in Lillooet and Lytton. On the south island of New Zealand, nephrite occurs as opiophites at contact points between deep mantle serpentine and igneous rock, especially in the Dun-Mountain Ophiolite Belt. The Maori people value nephrite or kawakawa as”pounamu” which are treasured family heirlooms passed down through generations as adzes, knives, chisels, fishing hooks, weapons and jewelry. Nephrite is treasured by the Chinese, who have used it for carving for millennia and call it yù.

According to ‘Chinese Jade Through the Ages’ by Stanley Nott (1937), “it was believed to have qualities of the solar light, and so to have relationship with the powers of heaven”, and thus, appropriate to the “son of Heaven, the Emperor”. At one time, the Chinese supply of nephrite came from the “jade mountains” of Eastern Turkestan, now the Xinjiang Uyghur Autonomous Region. But increasingly, the Chinese have looked to British Columbia for supply of nephrite jade.

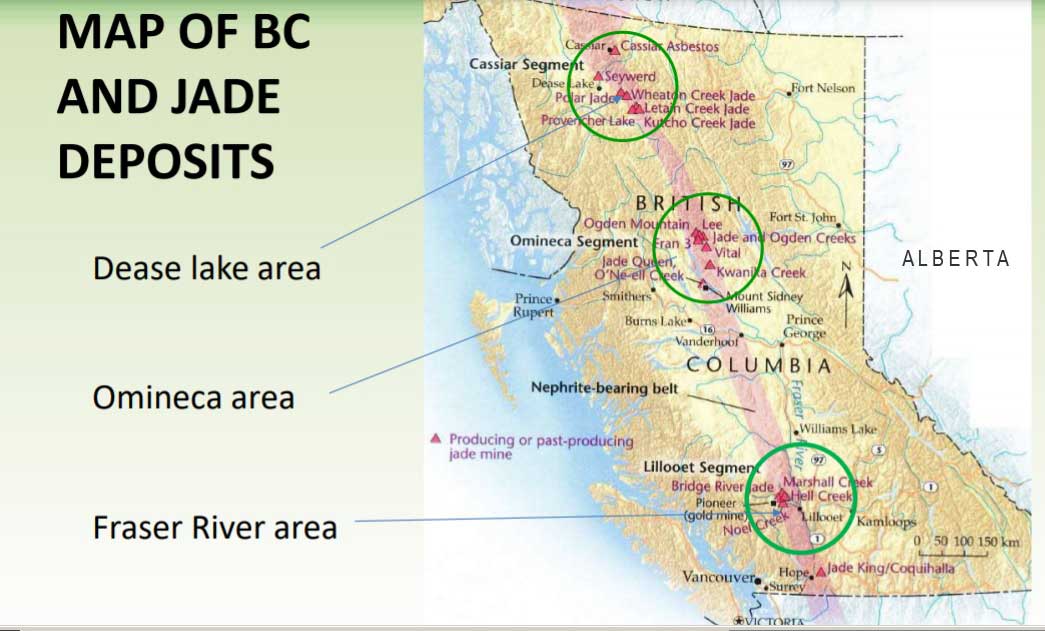

B.C. nephrite jade occurs in three regions in a belt that extends the length of the province comprising what geologists call the Cache Creek Terrane, part of the Canadian Cordilleran “accretionary orogen”. The CCT is what geologists call a “suspect terrane” because its constituents, i.e. rocks, fossils, etc. do not fit with its current location. When it accreted to or docked on the North American continent, ophiolitic serpentine from the ocean crust was emplaced on land.

The CCT (now grouped in the Intermontane Superterrane) is one of a number of exotic or suspect terranes that ultimately made up what we know as British Columbia, accreting from the west through the eons, either from ocean crust or island arcs.

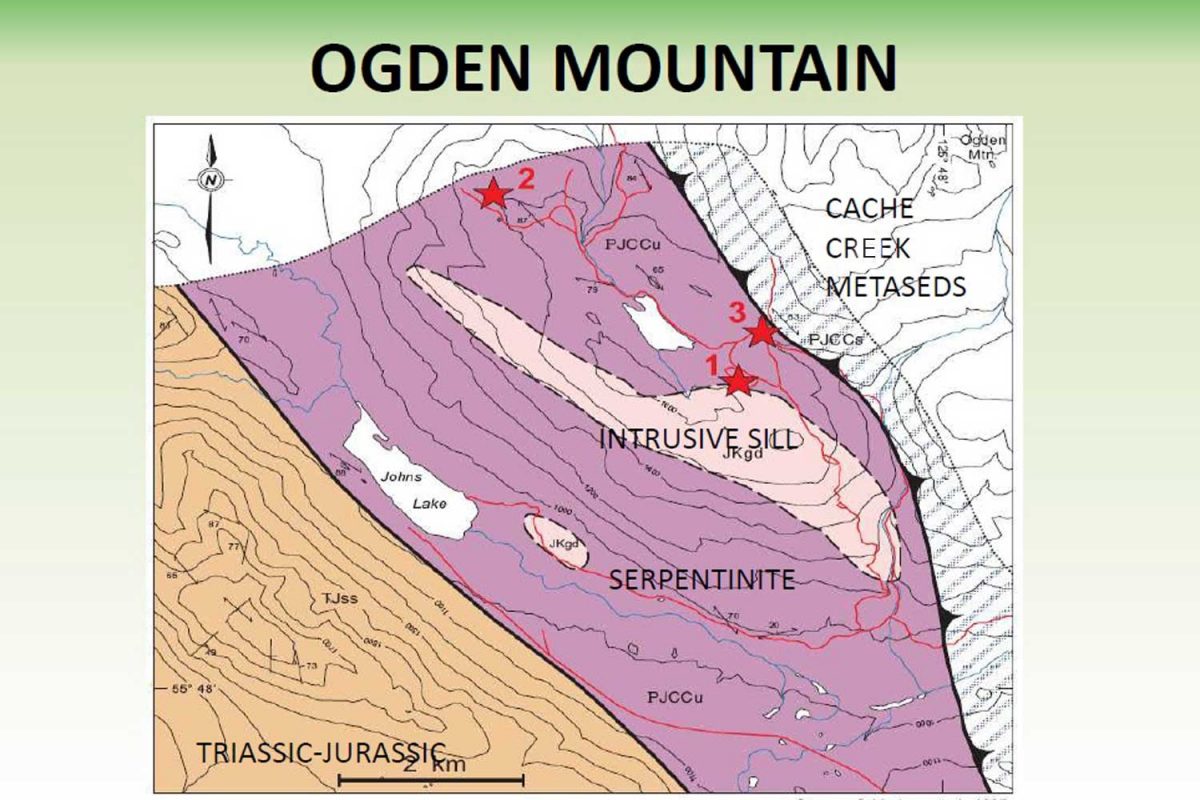

As for New World Jade’s property on Ogden Mountain in the Omineca Segment of the Cache Creek Terrane, as geologist Barry Price wrote in a 1988 report: “Nephrite bands and lenses occur at the contact of sheared serpentine of Permian or Jurassic age and metasedimentary rocks of Upper Paleozoic age (Cache Creek Group).”

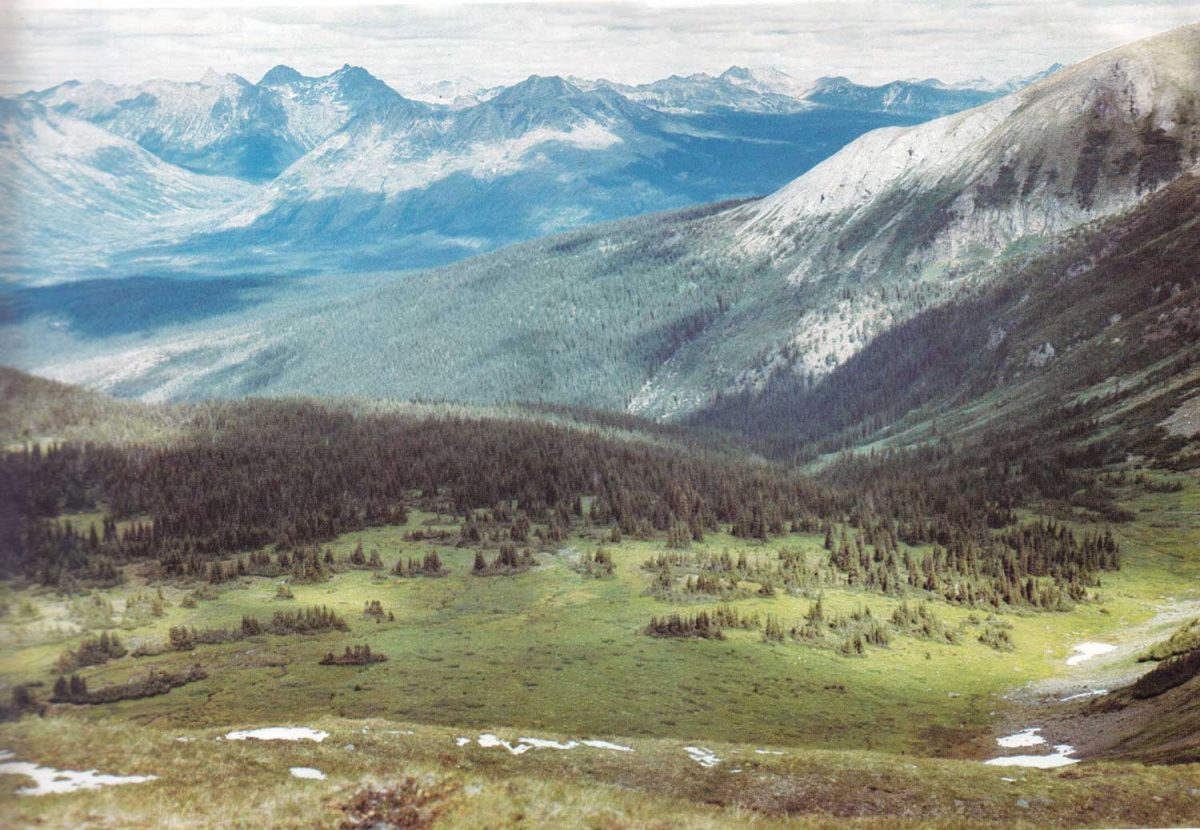

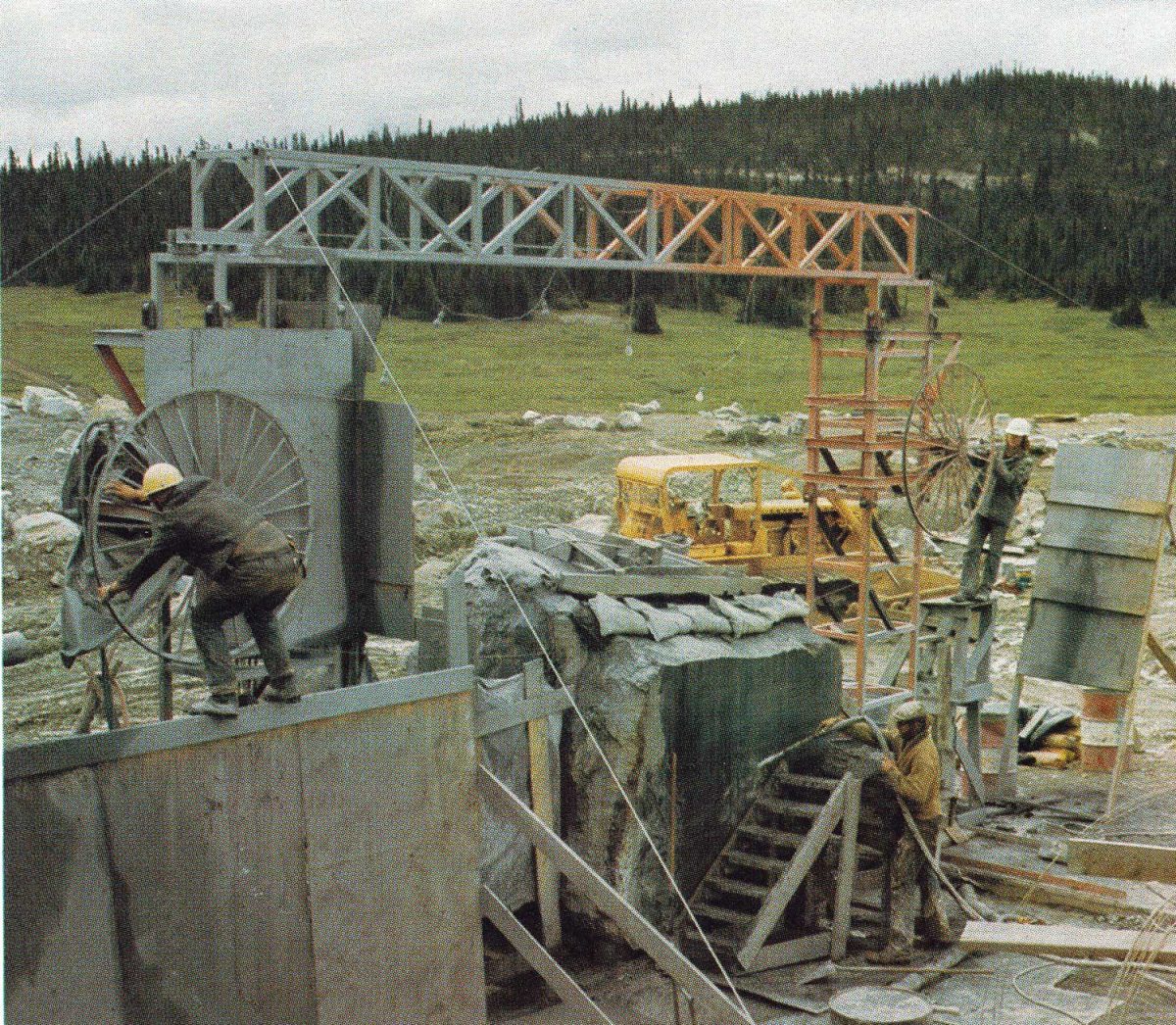

The property was in the Omineca Valley, below, where gold miners had tried their luck a century earlier in B.C.’s own version of the Gold Rush. Although nephrite jade mining, being small-scale and relatively rare, is not as damaging as large open-pit mines, it does require removal of the “overburden” (trees, surface soil) to access the seams.

New World Jade

My new job was not my first experience with British Columbia minerals. I’d worked one summer in high school in the occupational therapy department of a provincial home for people with developmental disorders. There I learned to run the grinding and polishing wheels, teaching people to work with semi-precious stones like agate, jasper, quartz and my favourite, pink rhodonite, below, to make cabochons that could be drilled and set into pendants or made into earrings. But it would be almost a decade before I was introduced to B. C. jade, at a time when the province was alive with “jade fever”.

Our company got its start in 1963 when a California high school principal named Larry Owen moved his family to Canada and bought a tiny village called Manson Creek (population 18) in the Omineca region 300 miles northwest of Prince George. Back in 1870, it had been a supply center for the Omineca Gold Rush. He planned to do some fishing, hunting and a little prospecting. He met a young man, a professional prospector named Stan Porayko who would later become his son-in-law; together they rambled around the countryside staking claims. In 1967, they found nephrite jade boulders in Ogden Creek. Two years later on July 9, 1969, at the 5000 foot level of 6000-foot Mount Ogden, while staking claims in a creekbed, they wandered down the slope and found the mother-lode. Said Larry Owen in a newspaper story in the Prince George Citizen, “We walked up to it, lit a cigarette, and sat down to relax. I took the drill off my backpack and both Stan and I sort of stared at this rock. We edged closer. It wasn’t granite. It wasn’t serpentine rock outcropping and it wasn’t like anything else we had seen before.” The photo below shows blocks of nephrite from the in-situ location being sawn in 1973.

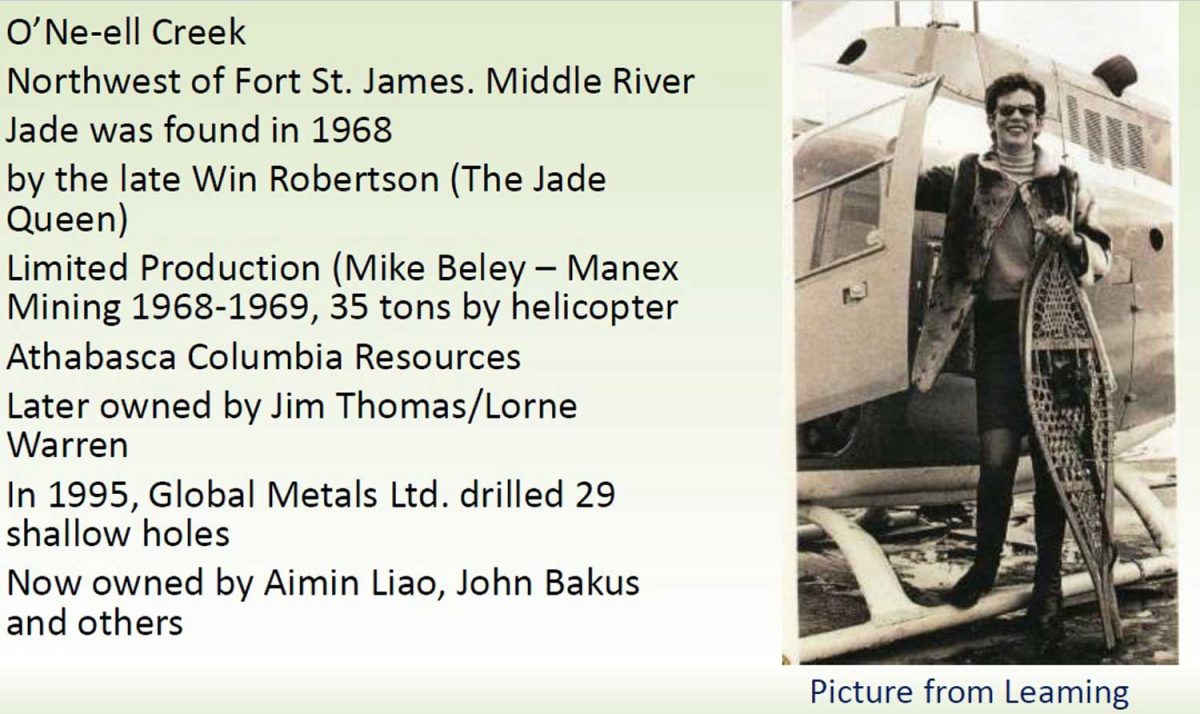

The initial ‘placer’ boulders from the creek yielded the first production from 1967-69. Once the ‘in-situ’ jade was discovered, it became necessary to secure outside investment to meet the costs of further exploration, production, transportation, storage, promotion and sales. In came two young Calgary businessmen, Gary Gallelli and David Saxby, and thus was born New World Jade Ltd., the company name alluding to the Chinese ‘Old World’ with its connection to jade. In fact, Dave Saxby was part of the Canadian Solo Trade Exhibit in Beijing in August 1972, one of the first cultural exchanges between China and North America. As word got out about the jade, the newspaper headlines became ever more colourful.

Mining happened in a short summer season, with rain, mud, mosquitoes and the remote location adding to the logistical issues.

After wire-saw cutting, helicopters were used to lift the sawn jade to the road….

….. where they could be trucked to the warehouse/office in Vancouver where I worked. Here they would be sawn with the whirring diamond saw blades and inventoried according to quality, i.e. colour and lack of inclusions and fractures. (As I recall, the lovely man on the forklift was named Eric.)

Inventory valuation was an interesting notion, since to the best of my recollection, the jade sold for between $50/lb for gem-grade to a fraction of that for ‘building grade’ jade for floor tiles, etc. Our customers were amateur rockhounds, jade carvers and of course China and Taiwan. But until large blocks and boulders were rendered into smaller pieces, there was no way of estimating the value of inventory – which is the essential problem with nephrite mining itself. It’s not like gold, with a known production value, it’s a crap shoot. Below you see Eric with the Ogden Mountain jade property founder Larry Owen, who bounded into the Vancouver office now and then wearing his bomber jacket and a big smile.

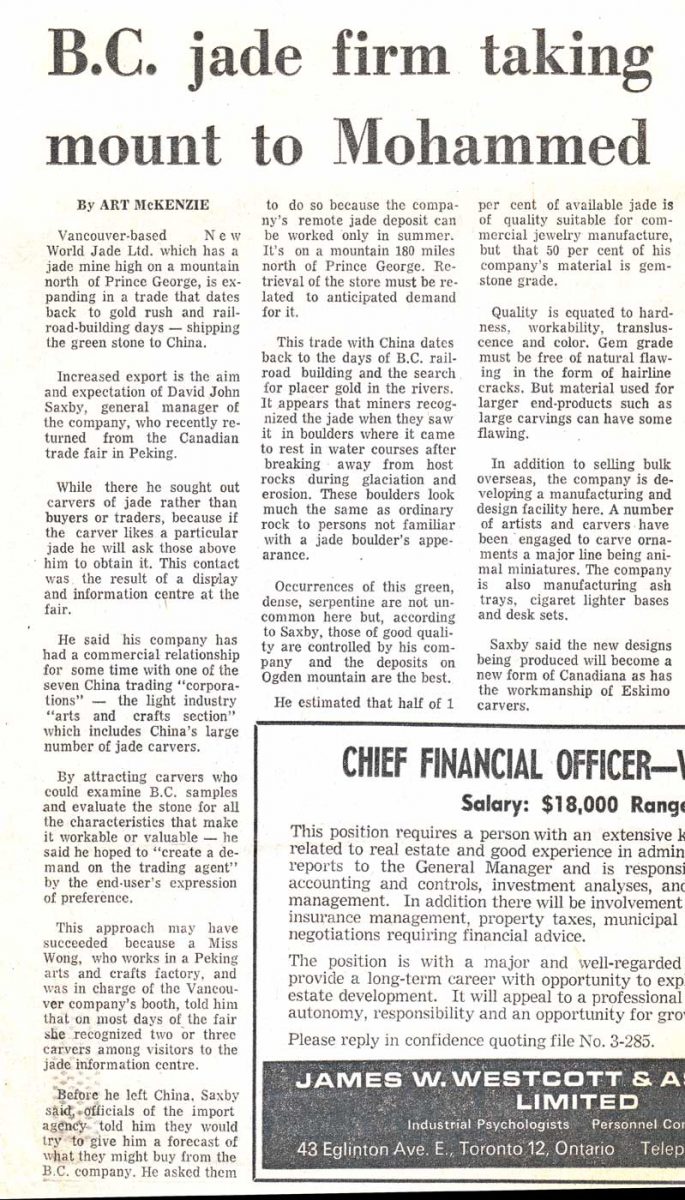

A neighbouring jade property that was struggling, Northern Jadex, was acquired by New World Jade, but it didn’t buy up all its competitors. The most interesting (and photogenic) was the woman the press would dub ‘the jade queen’, Win Robertson. A former television personality and occasional fashion model, she was also an avid rockhound with a keen understanding of where to look for jade (serpentine belts), developed through her friendship with geologists. In 1968, she and her son found piles of jade boulders in O’Ne-ell Creek on Mount Sidney Williams near Smithers. Overnight, she became famous, with Good Housekeeping magazine and the London Illustrated Times arriving for photo shoots. But like Larry Owen and Stan Porayko, she needed working capital, so she turned to a subsidiary of Vancouver’s Sandwell Company, Athabasca Columbia Resources, for financing. They became 51% owners of her jade mine. That transaction would become pivotal in how my own life turned out.

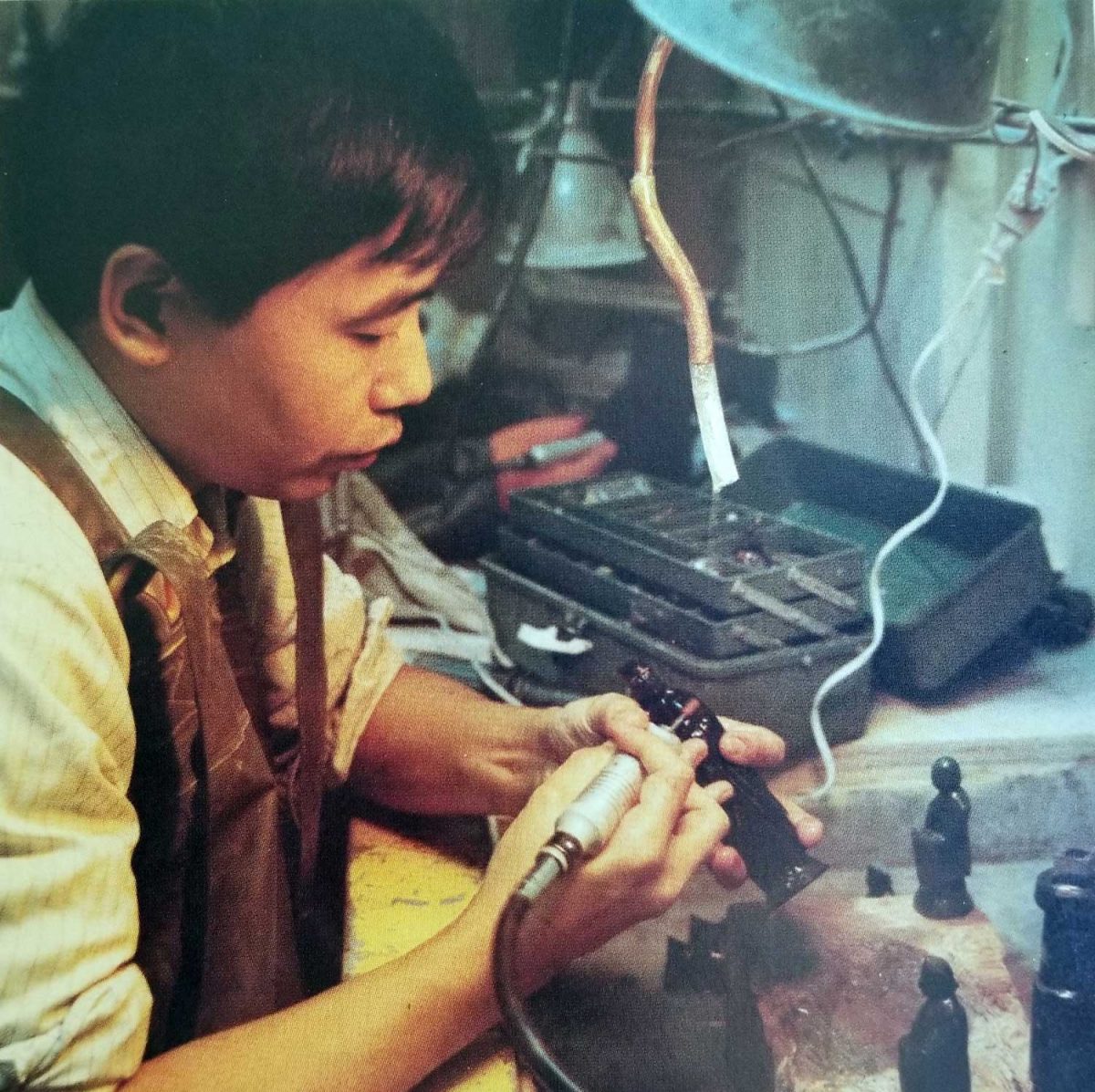

There was a second component to the New World Jade operation, the carving studio called New World Jade Products. Raw material was obviously not an issue and there were lots of young artists ready to learn how to carve jade. The carving studio launched in 1972 with Quebec-born sculptor Robert Dubé. As well, there was an opportunity to create small jade pieces and jewelry items on a mass manufacture basis, thanks to the talent of stone-cutter Al Hampson, who created special saws and equipment to work the jade.

David Wong, below, had emigrated from China in 1971, met Robert Dubé, and launched his jade-carving career with New World Jade in 1972, becoming one of the firm’s most prolific sculptors. He is carving a one-of-a-kind black and green jade chess set.

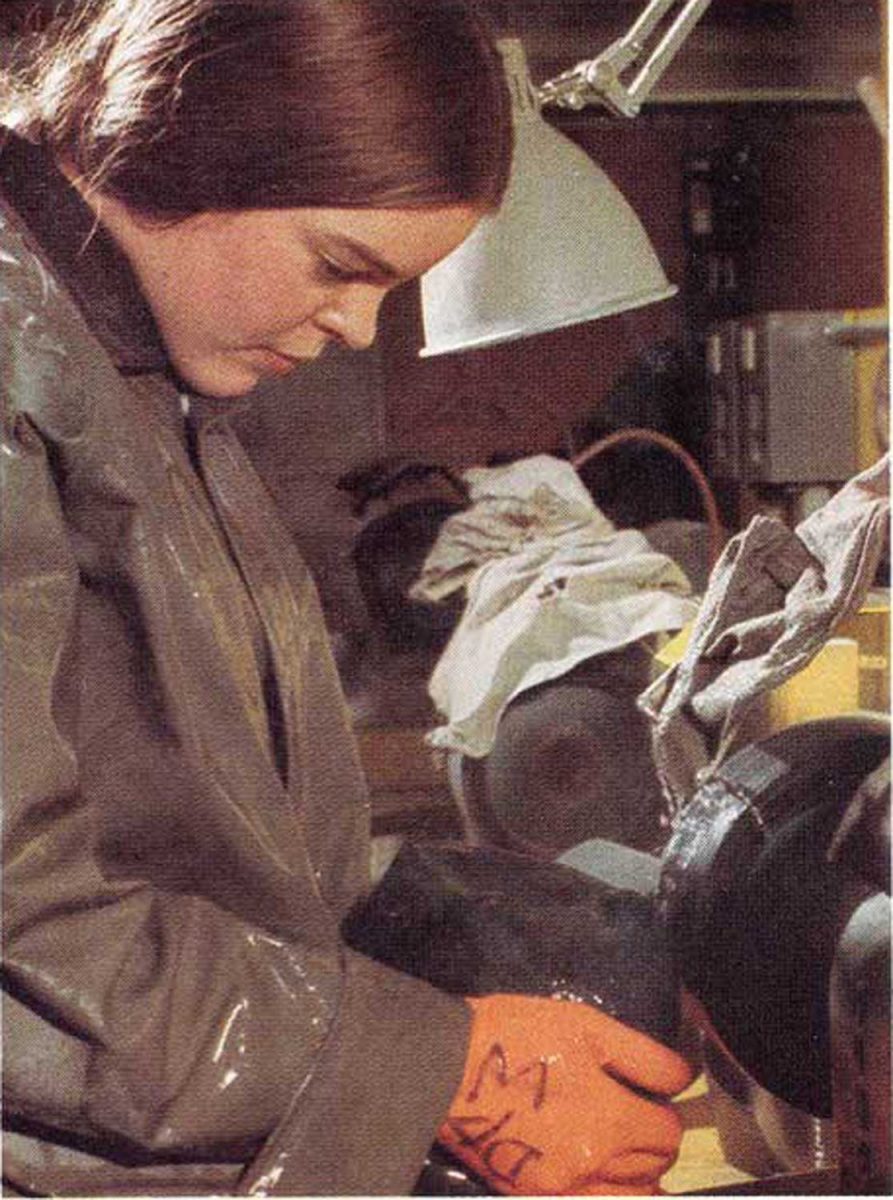

Deborah Wilson, below, began carving at New World Jade Products in 1973 along with several other graduates of the Vancouver School of Art. Today, almost 50 years later, she is a successful jade carver and teacher with her own Okanagan studio where she gives workshops to sculptors from every corner of the world.

Another VSA grad, Alex Schick, carved beautiful pieces. Today, he works in bronze casts and you can see him with an artist friend in this lovely video.

My administrative role with New World Jade expanded to accompanying the carvings to various art shows, including Dallas, Texas in a guarded-room containing $6 million in art from various places. I have old clippings showing me with a black jade buffalo by George Rammel….

…. and a bird in flight by Chuck Wiggins.

In December 1974, I was photographed with Gary Gallelli ‘playing chess’ with David Wong’s chess set, valued at $25,000. I didn’t know the first thing about chess, and certainly Gary didn’t have to worry about me dropping a piece (!) because as we’ve seen, nephrite is tough as steel.

The art studio was located on Cordova Street in Gastown, and in 1973 or early ’74, our office moved from West 1st Avenue to the newly-renovated historic Garage at 12 Water Street in Gastown. Our neighbour to one side was the radio personality Jack Webster; to the other side were music agents Bruce Allen and Sam Feldman (Bachman-Turner Overdrive, Bryan Adams, Sarah McLachlan, Joni Mitchell, Diana Krall). From time to time, late on a Friday afternoon, the office cupboard would open and a bottle would emerge. On those occasions, I remember Webster and his good friend, columnist Allan Fotheringham, coming in to join us for drinks while holding forth with rollicking stories. Another friend came by on the odd Friday night, a Toronto-born man who had been in the same Harvard MBA class as Dave Saxby and Gary Gallelli. His name was David Ingram, and we became good friends. From time to time, he brought with him a childhood friend from Toronto who happened to be working as a financial consultant for Sandwell Co. and had been assigned the task of finding a buyer for the jade mining company they now fully owned, Jade Queen Mines, Win Robertson having sold her interest back to the company.

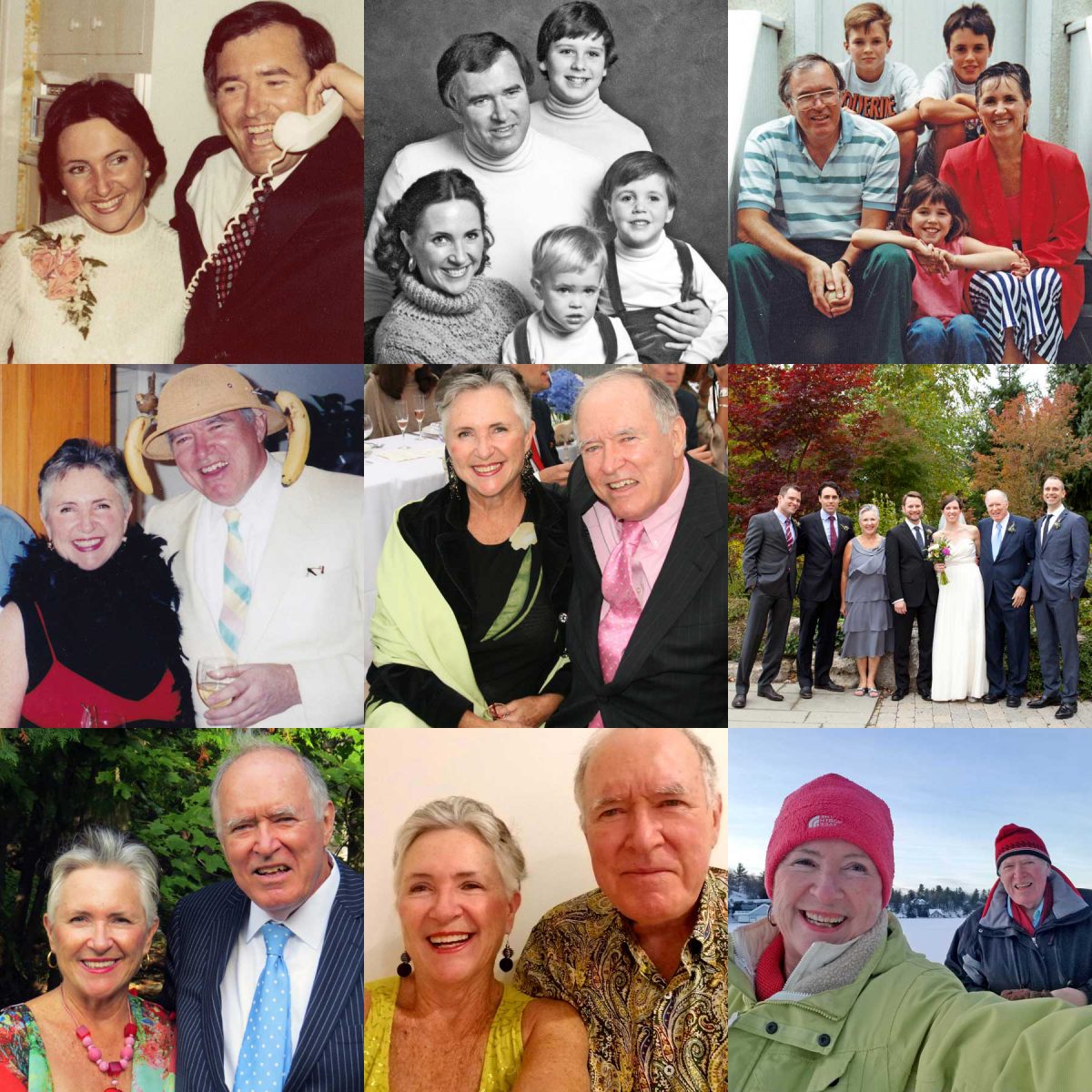

To make a long story short, the financial consultant was Doug Davis and in time, we moved beyond being ‘friends at the jade office’ to him actually asking me out on a date. Eighteen months later, we got married, our wedding attendant his 7-year old son who became the beloved big brother to his three siblings. The date was April 16, 1977, exactly 44 years ago today. And no, New World Jade did not buy Jade Queen Mines. In fact, we always joked that we were the assets that escaped, since the mining company was sold to Japanese interests and the carving company went into receivership.

Today, our living room shelf holds two beautiful carvings by David Wong – the whale a gift to me on leaving the company, the bird a wedding gift to both us – as well as a sea lion by Stan Schmidt rescued from the junk pile at the studio. Nearby are soapstone carvings that, unlike jade, are so fragile that movers managed to break one.

In my kitchen window, I have a ceramic planter of grape ivy that I planted in 1994 and have not divided or done a thing to since other than thinning its incredible growth. But it might be the only plant pot in Canada with a nephrite jade dust glaze!

Forty-four years is a long time to be married, and we’ve been lucky to have a good life and a wonderful family. I made the montage below with photos from 1977-2021. Once in a while, we even talk about the “jade days”, especially when I root in my jewelry box.

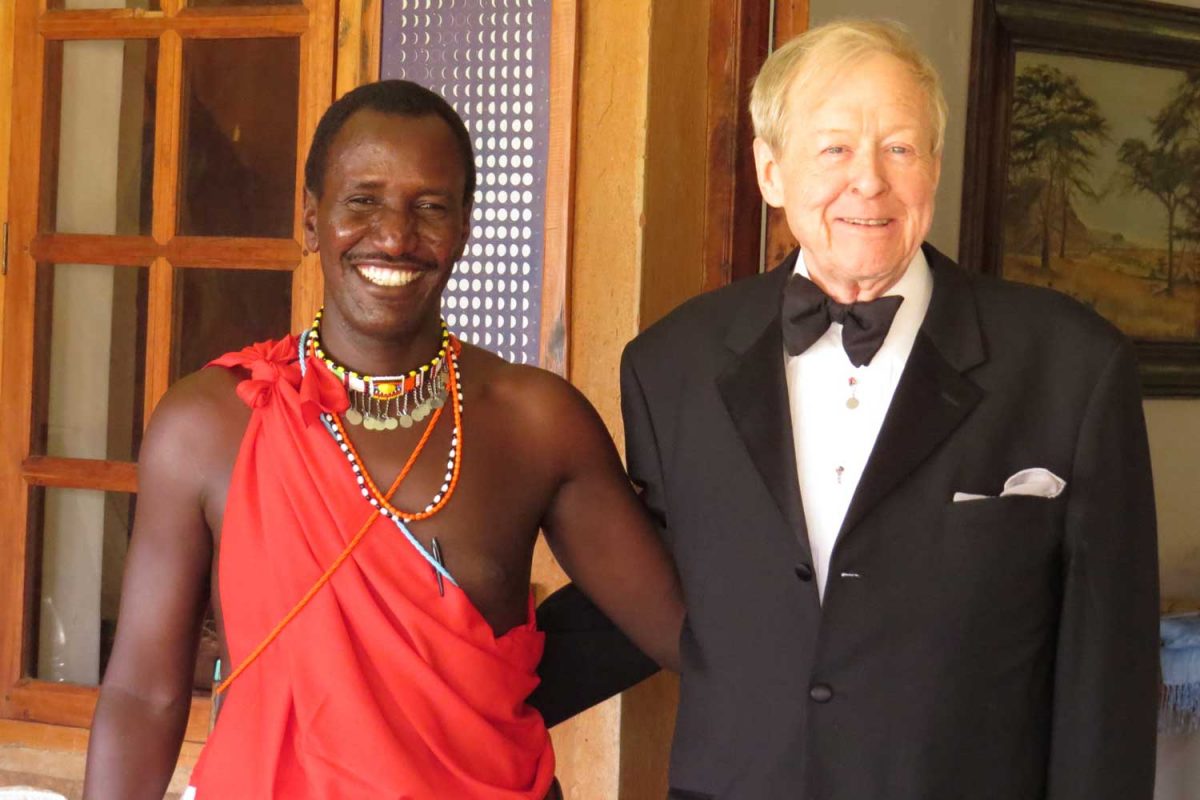

David Ingram remained a dear and very special friend to both of us for four decades, entertaining us when we travelled “home” to Vancouver and visiting us at our cottage and home in Toronto. His enthusiasm for people, places and business opportunities never flagged, but he was always so busily preoccupied that he sometimes tended to miss little details. When we were together last in 2016 in Kenya for the wedding of the son of a mutual friend, he forgot to pack the cufflinks and studs for his dress shirt. I suggested he ask Karmushu, the Maasai manager of the lodge if he could improvise. When his shirt was adorned with Maasai jewelry and we were about to leave for the ceremony, David asked me to take their picture together. Sadly, it was the photo the family would use on his funeral program nine months later.

I dedicate this blog to David Ingram, and to the late Larry Owen, Stan Porayko and David Saxby, as well as Gary Gallelli, the late Win Robertson, Barry Price, the late Stan Leaming and all the artists who worked their magic with British Columbia nephrite jade.

Wow! Janet! I am an avid home gardener in BC and stumbled upon your name while looking up Piet O. and the Toronto Botanical garden. I have subscribed to your blog now for only a few weeks and am amazed by how much you know and all that you have accomplished. I am not geologically minded, but enjoyed learning something new today. Thank you for your hard work!

Jody

Thanks so much, Jody! Be sure to read my blogs on VanDusen Botanical Garden

https://www.thepaintboxgarden.com/spring-at-vandusen-botanical-garden-part-1/

and the David Lam Asian Garden at UBC Botanical Garden:

https://www.thepaintboxgarden.com/may-in-the-david-c-lam-asian-garden-at-ubc/

Your blog today is fascinating. I have travelled to a few of these geological destinations, but have never reached your level of understanding or taken such amazing photographs. I will be rereading the blog and hoping to absorb and retain some of the details. Thank you for this informative post. Jane

Thank you, Jane. I have also done much research after returning home. When we’re on vacation, we’re completely preoccupied with the mechanics of travelling. When I return home, I often discover exactly where I’ve been.

Oh Janet. What a lovely, mystical journey from deep time to “today”, recorded with what I sense is a deep reverence for the “grandfather” rocks (in the language of indigenous people), that includes the stable and the itinerant. The weaving in and out of culture is so faithful to the fickle foundation created by the Earth’s 4.5 billion year journey. One can only dare to imagine what the next 4.5 billion years will hole. Thank you. Andy Fyon

Andy, thank you so much. It’s the greatest compliment, coming from you. The “itinerant”…. no one used that descriptor, but it’s perfect for those wandering arcs and crusts.

Never mind rags to riches–your very interesting blog post takes us from rocks to romance by way of reminiscence. Happy Anniversary, Janet and Doug!

Aldona, the late Jack Websterrrrrrrr (you had to hear him saying his name) would be happy with all your alliterrrrrration! Thank you. x

DS!

Loved this!

Great story and lots of rock learning!

Xo

DS!

I hope you don’t mind me showing 7-year-old you! You were such a cute wedding attendant.

xoxo

Hi Janet – Fabulous story about the history of BC jade mining – I have added the post to the VanDusen guide website at https://www.ericanotebook.com/store/p293/Jade_%28Nephrite%29.html And thanks for all the amazing pollinator information, which I have linked to when appropriate.

Thank you so much, Marilyn. I know it’s become a bit of a reality television topic now, but I did feel it was worth connecting to a blog on my ‘current’ love of geology. How I wish I could be at VanDusen again soon.

So great to have a window into your jaded history Mom! I liked learning about the characters of that time and place – Eric the forklift man, David Wong the master sculptor, and Deborah Wilson who’s still at it today. And I love the old photos of you.

Aw, thank you my sweet son. Yes, all the people from our distant past. It is so good to have photographs, these pictorial journal entries in our lives.