The morning after our visit to the Painted Hills Unit of the John Day Fossil Beds National Monument (JODA), we had a $5 bacon-and-eggs breakfast at the Sidewalk Cafe in Mitchell, then packed our bags and drove away from The Oregon Hotel.

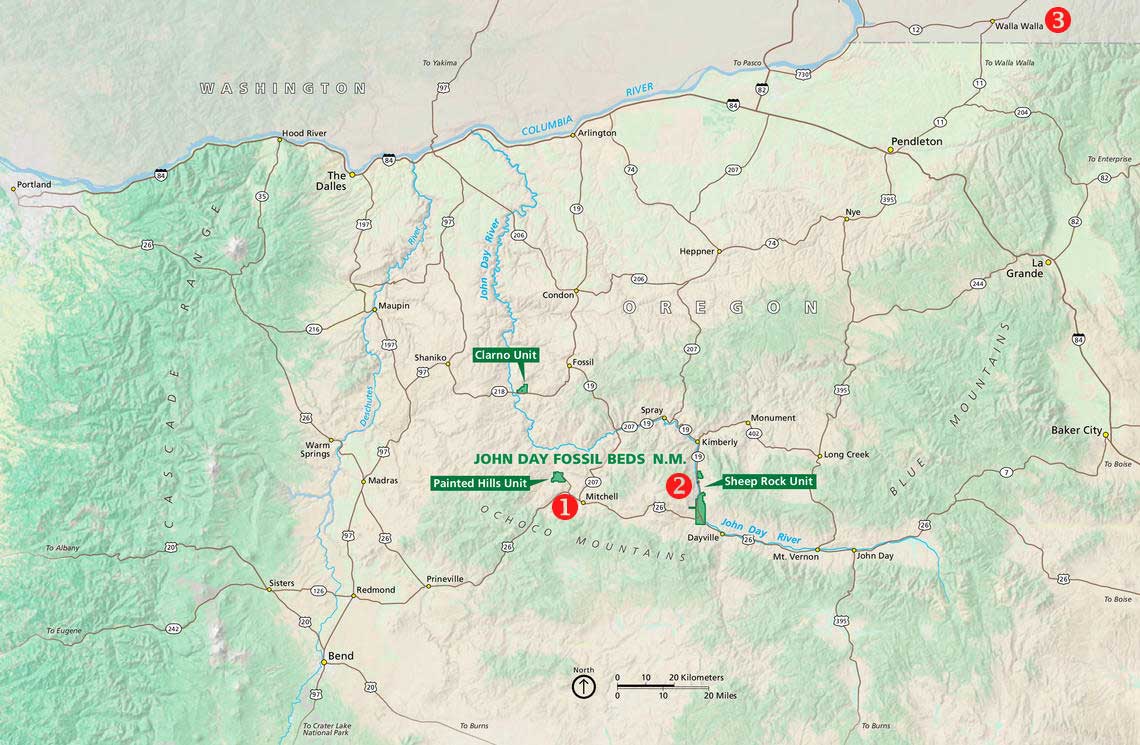

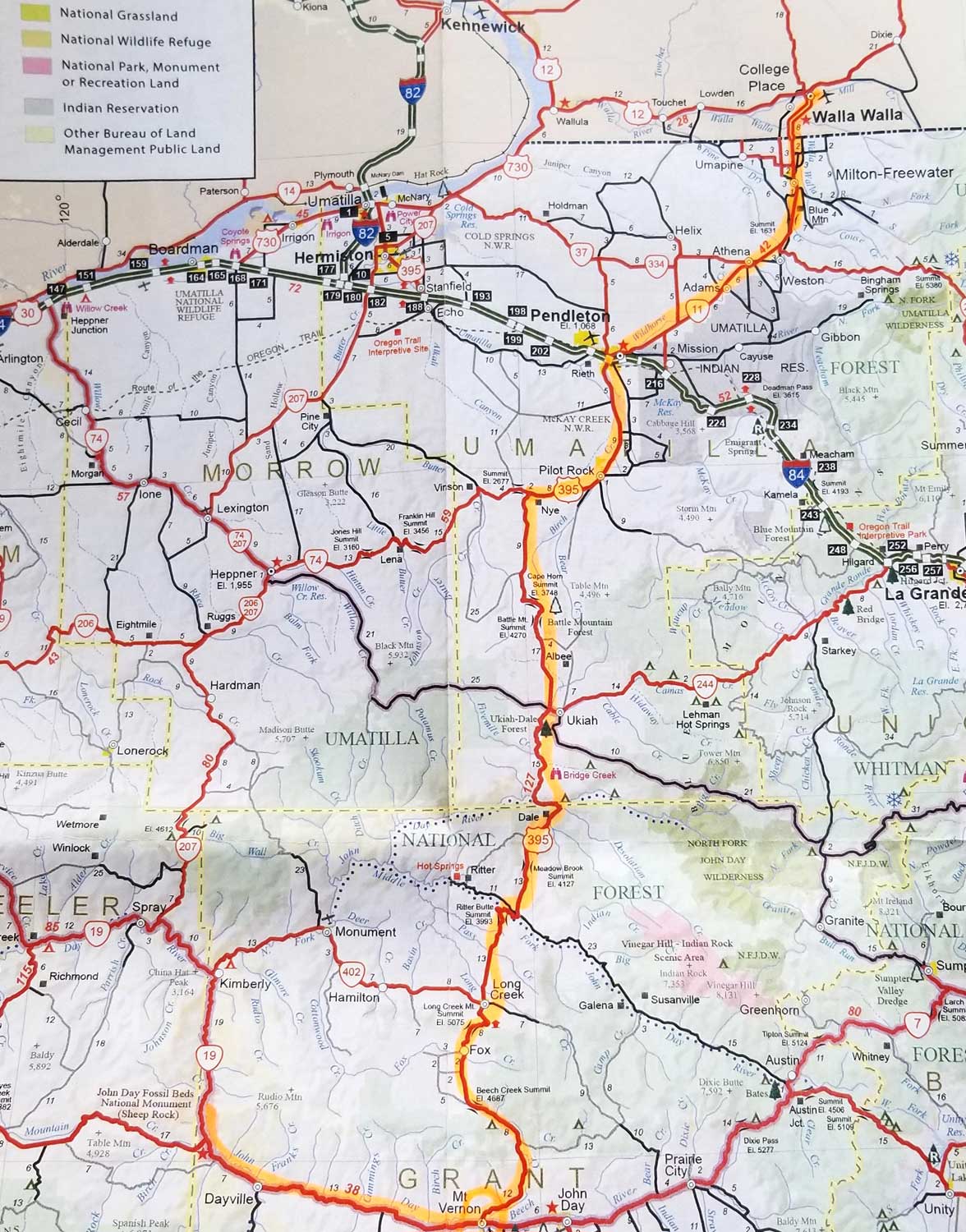

Soon we were driving east from Mitchell (#1, below) on Highway 26 towards Highway 19 and our destination, the Thomas Condon Paleontology Center (TCPC) at Sheep Rock (#2), the second of the three units of JODA. (Click on the photo to see a larger version.) Sadly, we didn’t have time to include John Day’s third area of interest, the Clarno Unit, which features the in situ fossils. Our ultimate destination that day was a one-night splurge at the Inn at Abeja in Walla Walla (#3) about 207 miles away via Highways 395 and 11, where my husband had booked a 3 pm wine-tasting. We didn’t make our appointment (blame geology and highway work) but re-booked it for the following morning (coming up in my next blog!)

It was fine weather on September 10, 2018 and I was enjoying…….

…… sending back jokey phone shots to my friends on Facebook. Might as well get some value out of those roaming fees! You can see the reddish-brown, wedding-cake palisades of the…..

….. Picture Gorge Basalts in these photos. “Picture Gorge”, for all its importance in defining a large lava flood, seems a little elusive as to physical definition. It is usually pinpointed on maps as just north of Highway 26 on Highway 19, i.e. very near to this location. So it was fortuitous that I asked my husband to pull over at this spot on the highway where the volcanic rock was beautifully exposed. It recalled for me John McPhee’s writings in Annals of the Former World about road cuts like this one yielding vital information for geologists.

At this point we saw that the basalt has been tilted and mashed up (using very un-geological terminology), but a few yards further on…..

…… we saw the basalt as it was originally formed into hexagonal columns (columnar basalt) while cooling slowly after a geographically local eruption in what geologists include as the “Picture Gorge Basalt Flood” in the Columbia River Basalt Flood (CRBF) event. As defined in Wikipedia, “a flood basalt is the result of a giant volcanic eruption or series of eruptions that covers large stretches of land or the ocean floor with basalt lava”. The broader geologic category covering basalt flood events is a Large Igneous Province (LIP), meaning areas greater than 100,000 square kilometres (38,600 square miles) that occurred within a short geologic time, a few million years. (If you remember your three types of rock from elementary school, “igneous” rock forms from lava or magma.) In this part of western North America, the Columbia Plateau between the Cascade Range and the Rocky Mountains of Washington, Oregon and Idaho is a depression of 160,000 square kilometres (63,000 square miles) formed by successive lava flows. During the CRBF event between 16.6 – 15Ma (Ma = mega annum = million years), massive amounts of magma erupted as basaltic lava (thought to have been fed by the same slowly-moving hot spot that triggered the Yellowstone super-volcano). The CRBF covers seven formations, including the one we’re travelling through: the Picture Gorge Basalt Flood. Beneath Yakima, Washington, the basalt is 15,000 feet thick. Here in the Picture Gorge, it’s about 1,000 feet thick. Got all that?

Less than an hour after leaving Mitchell, we were on the newly-paved highway through Picture Gorge leading to the TCPC. We stopped to photograph pinnacled Sheep Rock with its patchwork formations.

Sheep Rock is 3360 feet (1024 metres) and gives its name to the larger area around it. According to the US Geological Survey, “The Sheep Rock unit contains an amalgam of colorful strata and complex geology. From Cretaceous conglomerates to the flood basalts, the geologic features in this portion of the monument are a spectacle to behold. The predominant exposures of green rock seen on Sheep Rock are a multitude of reworked layers of volcanic ash. The rich green color of the claystone was caused by chemical weathering of a mineral called celadonite. This happened millions of years ago as water moved through the alkaline ash beds under high pressure.”

We stopped further down the road so I could photograph it with the eponymous John Day River in the foreground. If we hadn’t been pressed for time, it would have been good to explore the Sheep Rock Unit for a few hours, since there are trails here with startling blue and green formations and visible fossils, including Cathedral Rock and Blue Basin. You can see some of the other features in this blog.

But time was marching so we were soon parked at the Thomas Condon Paleontology Center. Mandated in the 1975 legislation that established JODA, it was opened in 2005.

We walked past a chunk of 40-million-year-old petrified wood in the parking lot. This was going to be fun!

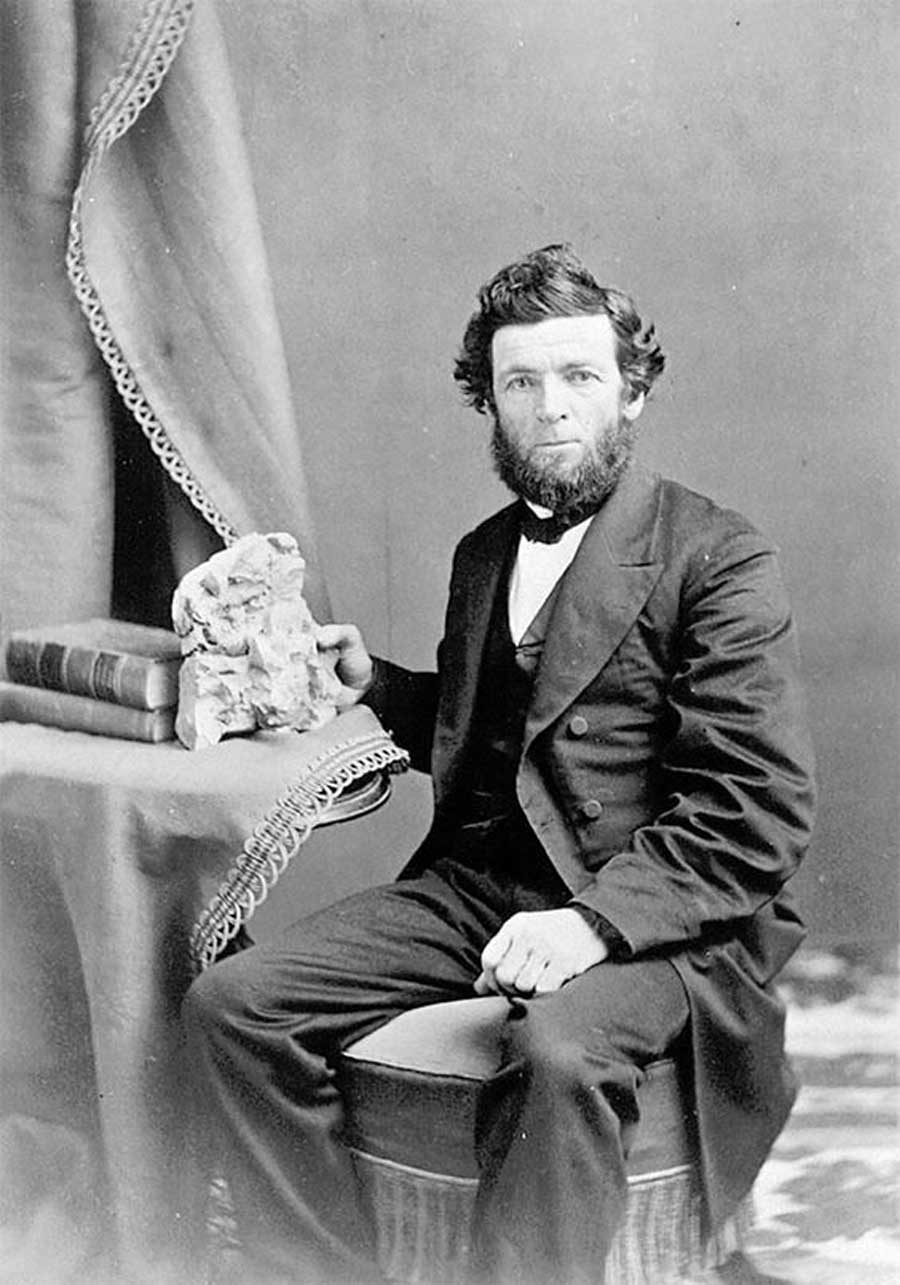

The center was named for Oregon’s first state geologist. Born in Ireland in 1822, Thomas Condon immigrated to New York with his family as a child. He became a school teacher then entered a Presbyterian seminary. Like many young educated men of his era Condon was also interested in natural history and collected fossils as a hobby. After moving to Oregon as a missionary, he and his wife later moved to The Dalles as minister of the Congregational church where one pioneer later remembered “that peculiar smile wreathed about his face when he spoke, the tender manner in which he handled the bones and rocks, his quaint manner that is indescribable. He read truths in God’s books of sand and stone.” When the soldiers in his congregation began bringing him specimens from the John Day area, his interested was piqued and in 1865 he travelled into the region with an army patrol. He sent the fossils he collected to eminent paleontologists for identification, and soon experts from Yale, Princeton and the University of California were writing Condon to request specimens (many new to science), or visiting the site themselves. At 49 he published a paper on Oregon’s geological past and gave a series of popular lectures on geology in Portland. In 1870, his first discovery was published by University of Pennsylvania paleontologist Joseph Leidy.

In 1872 Thomas Condon was named Oregon’s first state geologist; the following year, he resigned his church position to become a professor at Pacific University. Three years later, he moved to the new University of Oregon, below, where he taught for almost 20 years until his death in 1907. It’s a mark of his early influence that “by 1900 over 100 papers had been published on the geology and paleontology of the John Day basin”, according to the center.

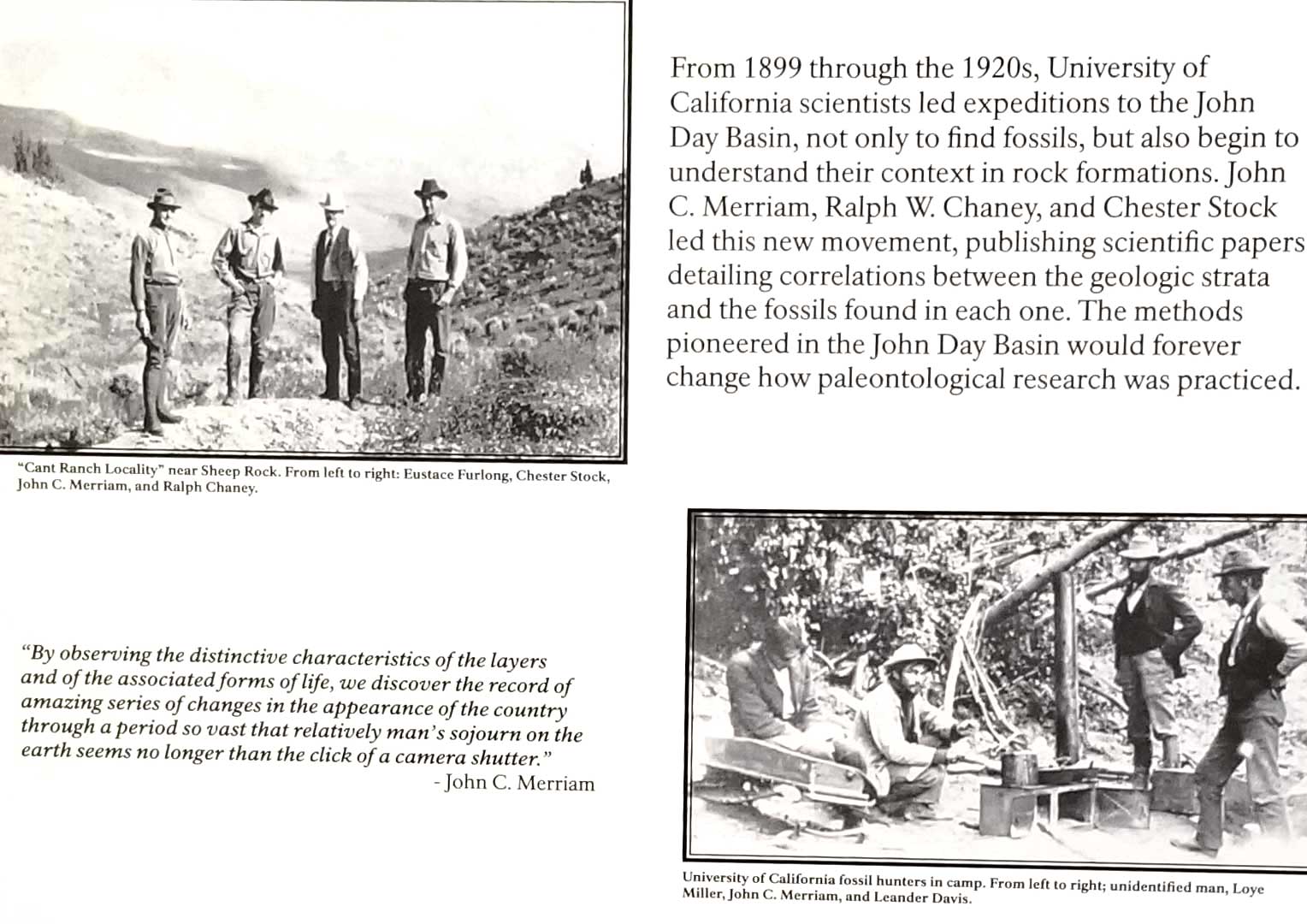

In fact, the John Day Basin was the first site to help scientists understand the historic global context in which fossils appeared in rock strata. Said John C. Merriam who led many expeditions to the region for the University of California in the early 1900s: “By observing the distinctive characteristics of the layers and of the associated forms of life, we discover the record of amazing series of changes in the appearance of the country through a period so vast that relatively man’s sojourn on the earth seems no longer than the click of a camera shutter.” One of the young scientists who visited John Day with Merriam was Ralph Weeks Chaney (1890-1971), far right in the upper photo below. A geologist, paleobotanist and ecologist, his collections helped to define the Tertiary flora (66-2.6Ma*) of ancient Oregon. At 35, he had published papers on the local Mascall 15Ma (see later in this blog) and Bridge Creek Flora 33Ma. At 41, he was named Professor of Paleontology at Berkeley and Curator of Paleobotany and Museum Paleobotanist at the University of California Museum of Paleontology.

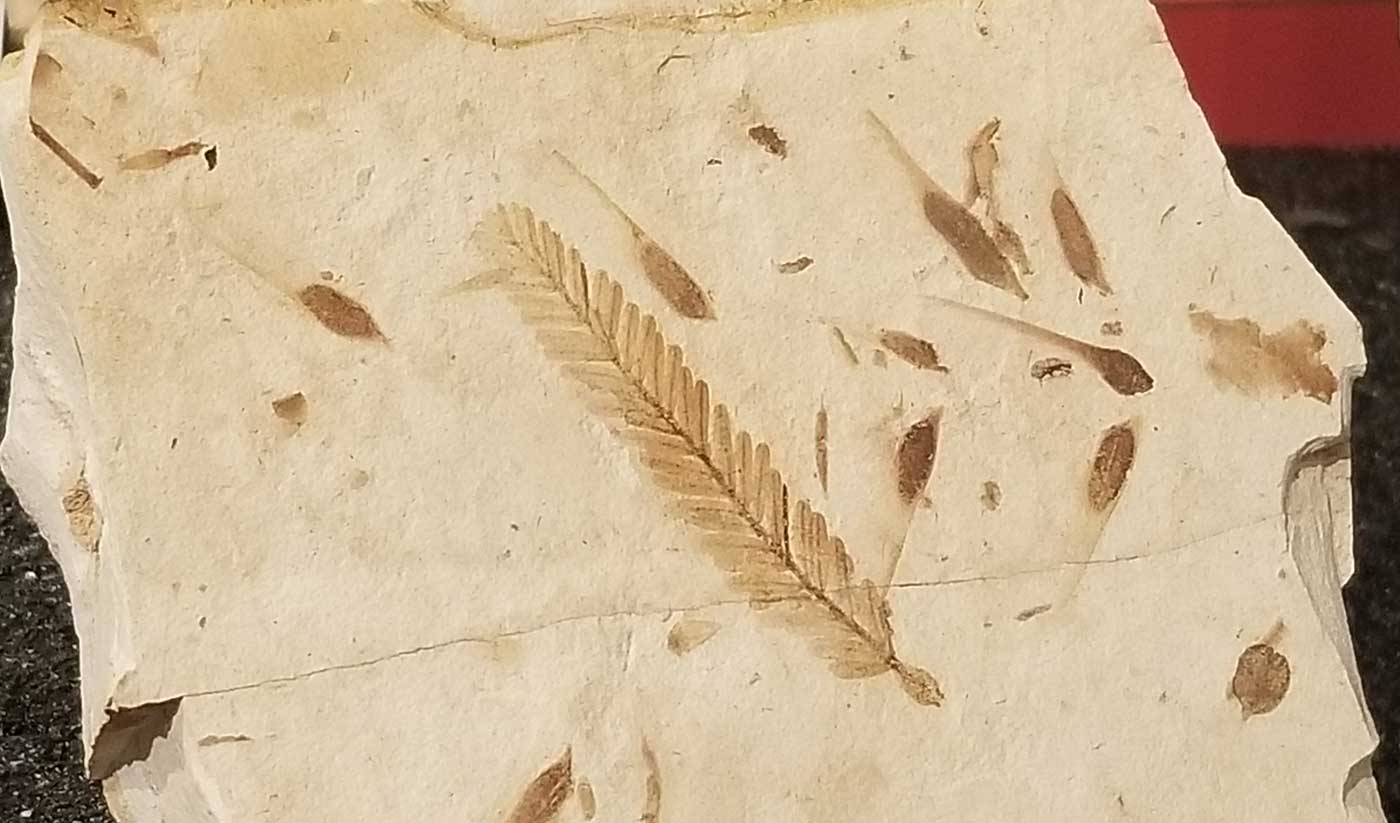

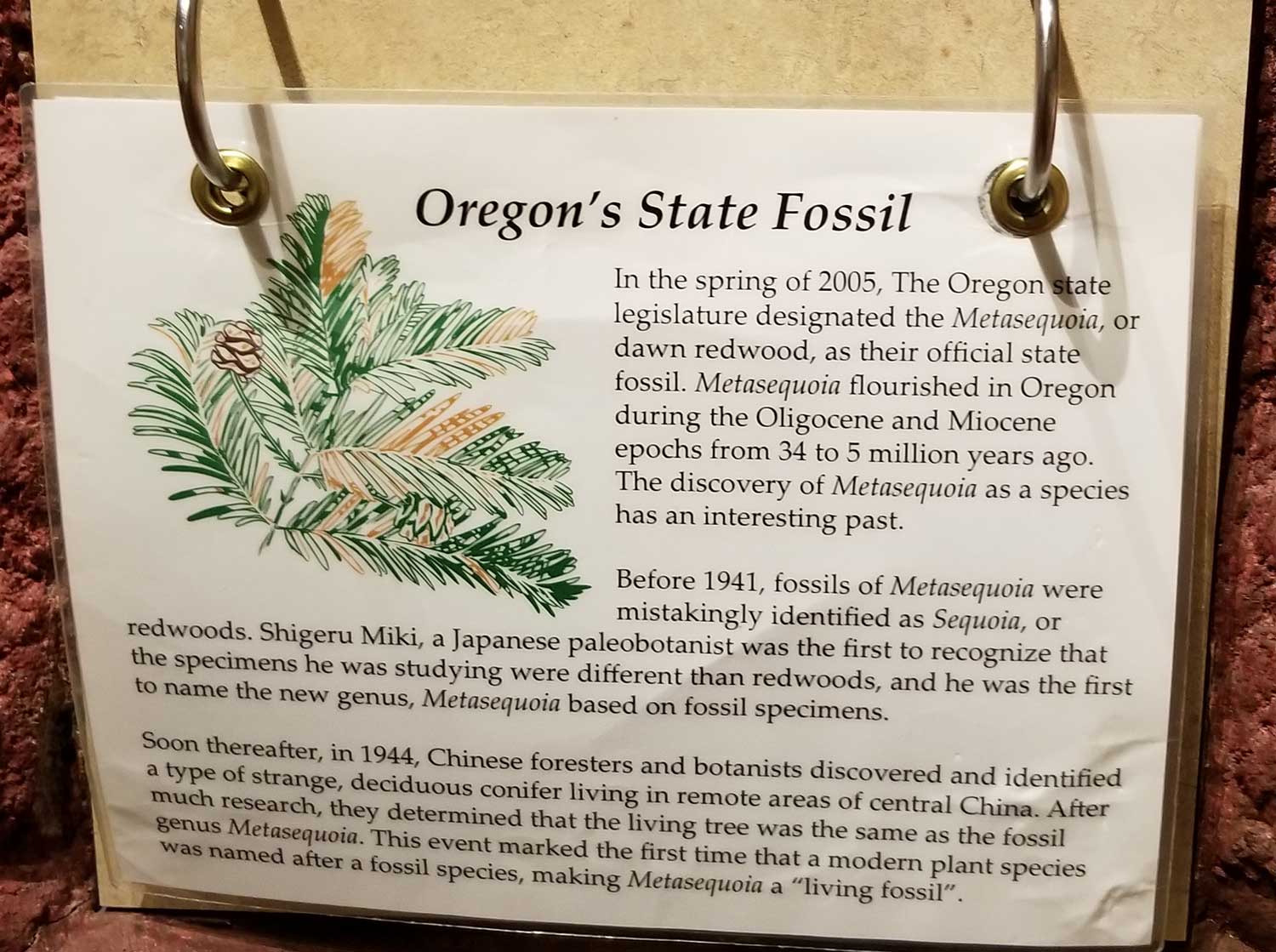

I would not connect the photo above with the photo below until a year later, i.e. right now, as I did my research on the region. When Chaney worked on the fossils of the Bridge Creek flora in the 1920s, specimens like the one below were initially identified as fossil Sequoia. But in 1941, a Japanese paleobotanist named Shigeru Miki found fossils of a conifer believed to be extinct in clay beds at Hondo on Kyushu. Because it looked like a sequoia in many respects but was not, he named the fossil Metasequoia. Then in 1944, a young Chinese forester named Zhang Wang went to a town called Mou-tao-chi in a valley in Hupei Province and collected branches and cones of a conifer that was thought to be a common Chinese species, the water-pine (Glyptostrobus pensilis). It was later determined to be an undiscovered species that matched the fossils found in Japan five years earlier: the dawn redwood. In 1947, collections of seed were financed by Dr. E.D. Merrill of Harvard’s Arnold Arboretum, who sent them to botanical gardens throughout the world. Ralph Chaney, through his own communications with the Chinese geologist Hsen Hsu Hu, learned about the new species at the same time, and suspected it might be the same “sequoia” fossil he had studied in the John Day Region. Accompanied by Dr. Milton Silverman, science writer for the San Francisco Chronicle, he travelled to Hupei in 1948; together they made an arduous 10-day trip into the region (one of Chaney’s 9 collecting trips in Asia), later leaving China with seeds and four small seedlings of dawn redwood. (If you’re not bored to death yet, there are layers of intrigue and professional misunderstanding in the Metasequoia saga, as described in this 2016 story in Landscape Architecture Magazine.)

Ralph Paley wrote his own story about the trip (which would overturn significant parts of North American taxonomy as nine fossil Sequoia taxa were renamed Metasequoia), which is included in a 1998 edition of Harvard’s Arnoldia. At the end is an epilogue on his return to the U.S. with the samples he had collected. “Chaney himself brought back seeds and four seedlings from China. Concerned that his prizes might be taken from him by customs in Hawaii, he tucked the seeds and twigs into an inner pocket and requested intercession for the seedlings from a former student at the Department of Agriculture in Washington. Word did not reach the inspector at Plant and Economic quarantine in Honolulu, however, and he demanded that the four seedlings be handed over for incineration. Chaney’s protestations that the trees were priceless, more than a million years old, were of no avail. According to Milton Silverman, the ensuing argment grew louder and louder until Chaney, close to hysteria, was shouting defiantly and citing, ‘millions of years, tens of millions of years, a hundred million years’. Suddenly the agitated inspector asked a question: ‘Are they more than a hundred and fifty years old?’ And so, officially declared antiques, the seedlings continued their journey to California”. Ralph Chaney would grow dawn redwood in his “Tertiary garden” in Berkeley, in a collection marking 100 million years of geologic time. I made the photo below in the Sarah Duke Garden at Duke University in North Carolina.

Oregon was so proud of the renaming that it declared dawn redwood its state fossil.

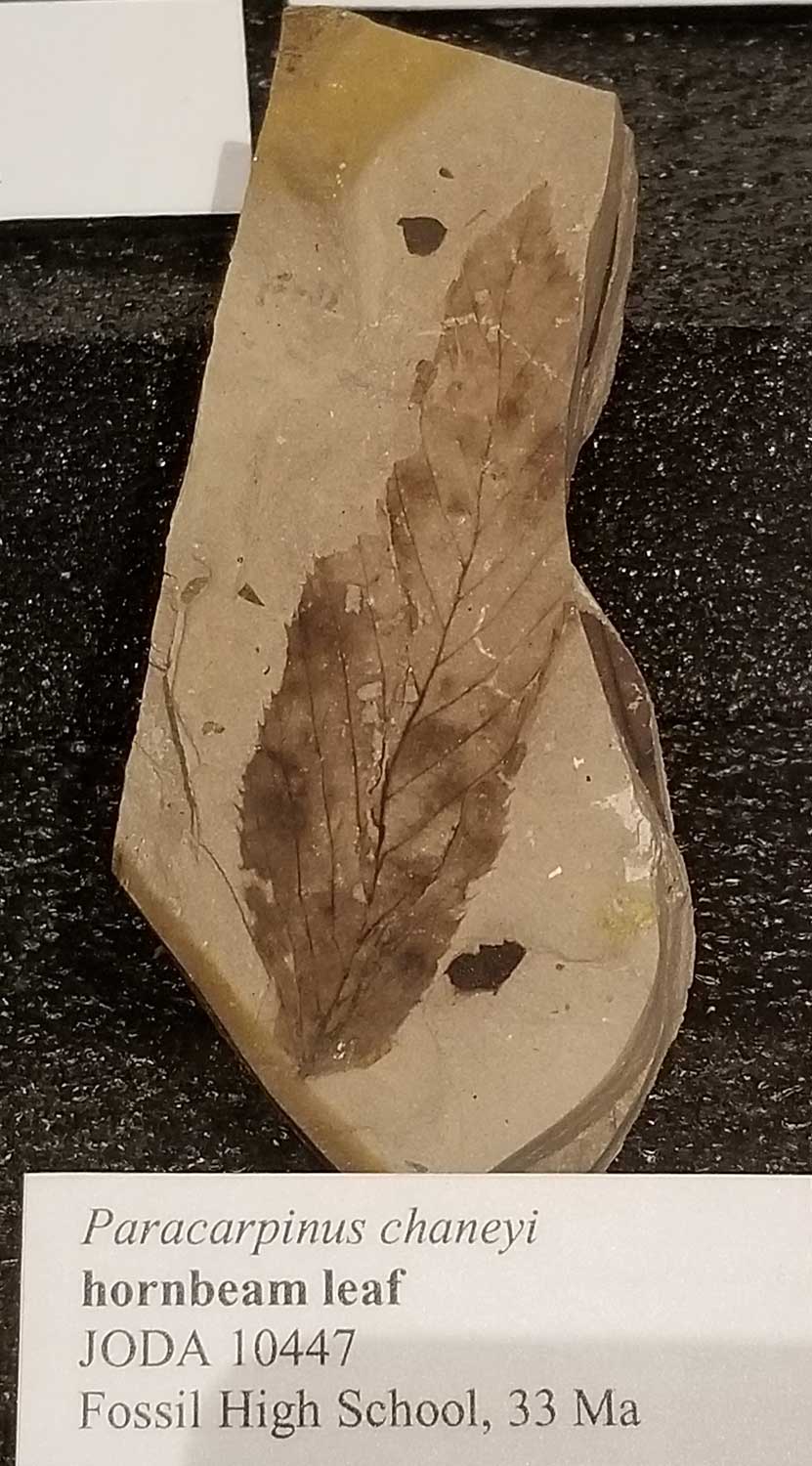

A fossil species of hornbeam from 33Ma is in the center’s collection, below. It is named Paracarpinus chaneyi after its discoverer. The maple fossil Acer chaneyi is also named for Ralph Chaney. These ancient ancestors of our modern-day trees, including katsura, elm and alder – and of course dawn redwood – are displayed in the Bridge Creek Flora section of the TCPC.

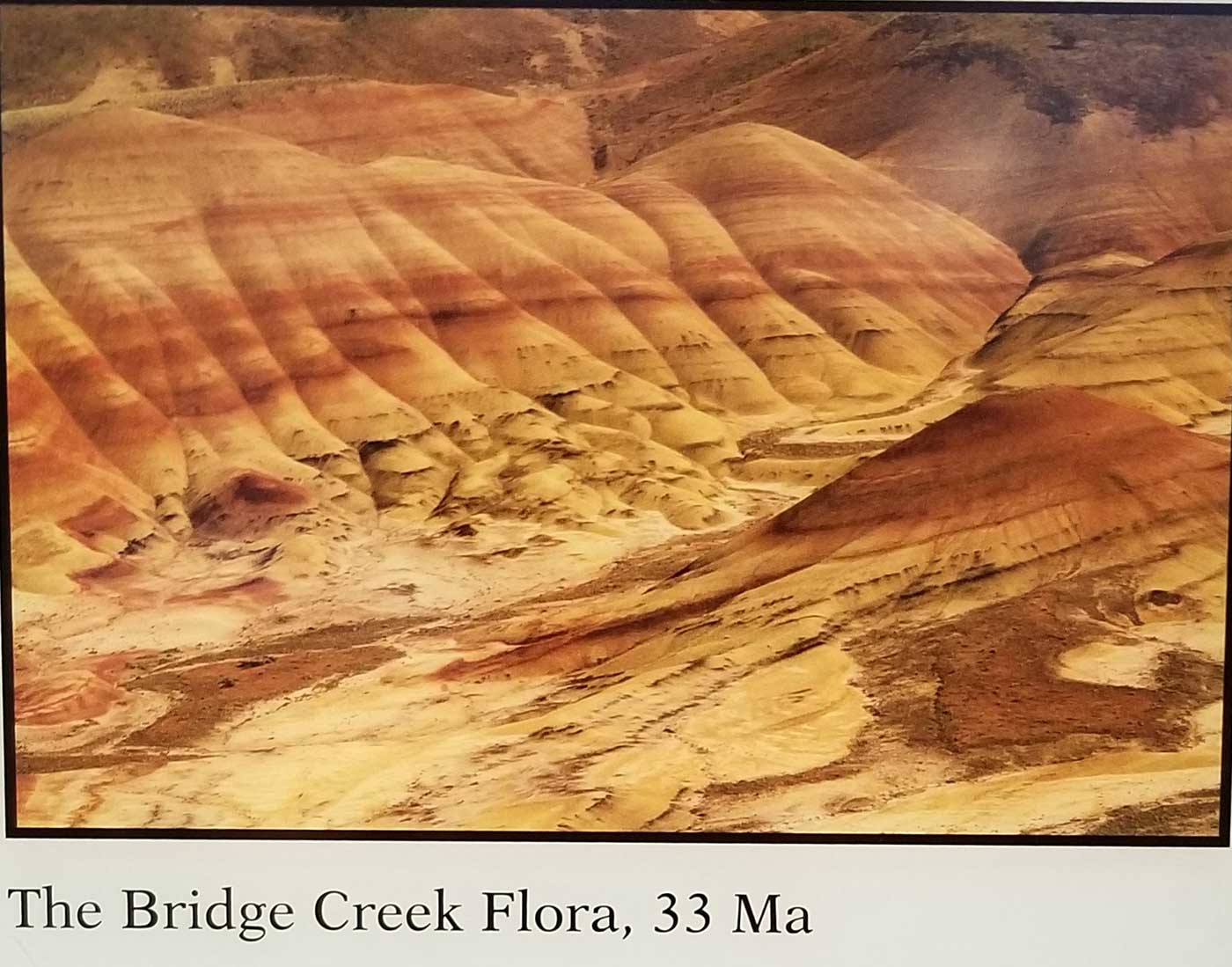

The Bridge Creek Flora was collected in the spectacular Painted Hills Unit of JODA, which I wrote about in my previous blog.

I loved the colourful displays showing an imagined scene from the Bridge Creek era some 33 million years ago (Oligocene). Check out the “painted hills” stripe in the wall.

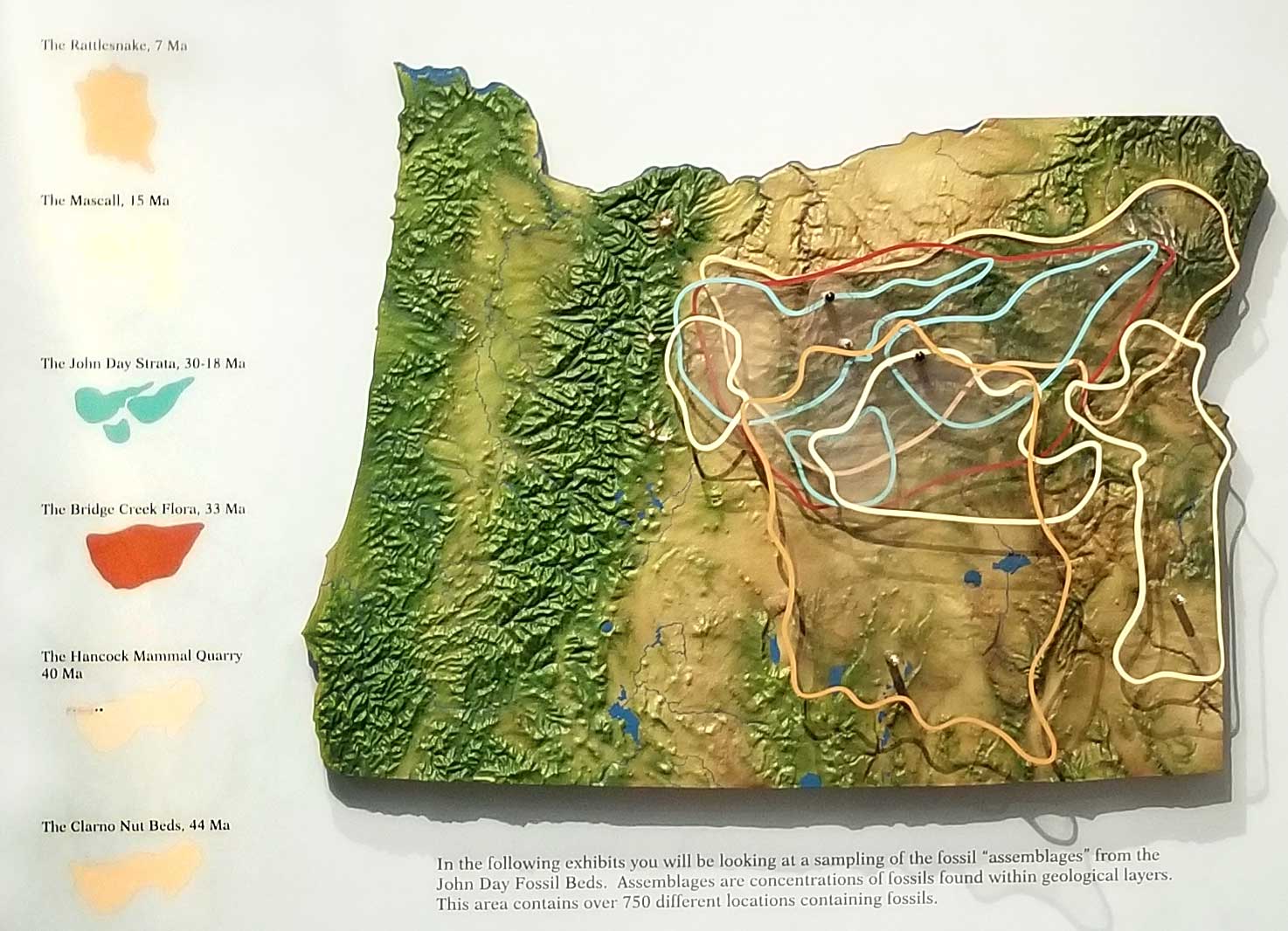

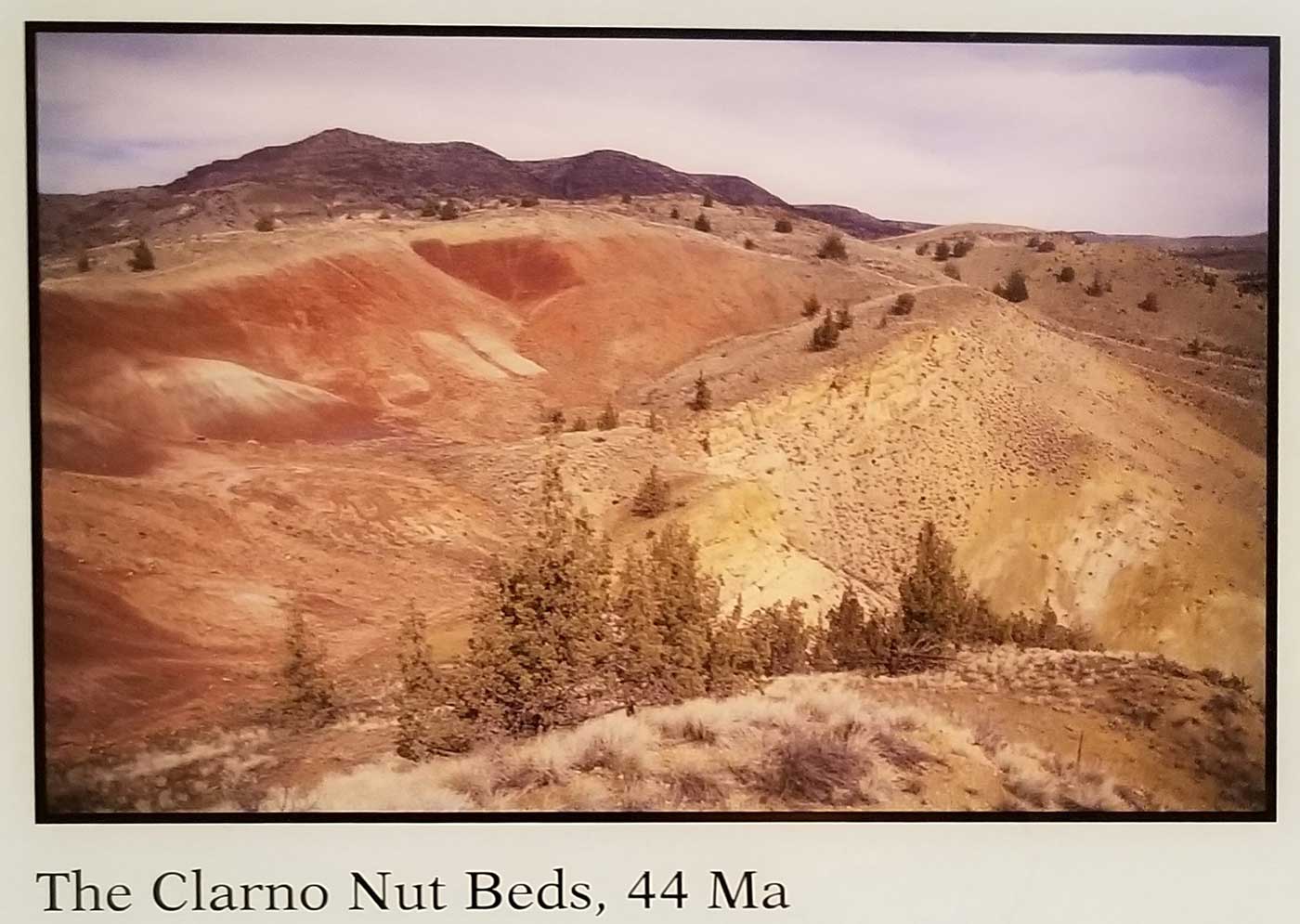

But the Bridge Creek Flora is not the oldest formation in the region. As you can see on the interesting display below, that honour goes to the the Clarno Nut Beds which make up the third unit of JODA (which alas we did not have time to explore).

The Clarno Formation is made up of volcanic mudflows called “lahars” that formed 54-40 million years ago, engulfing the forest and its plant and animal inhabitants. Fossils are visible in the cliff walls here.

The Clarno Nut Beds contain 76 species of wood, more wood than any other fossil assemblage in the world, including ancient relatives of walnut, chestnut, oak, sycamore, maple, linden, dogwood and meliosma. The region was a semi-tropical forest in which grew ancient forms of cycad, palm, avocado, banana, grape and horsestail. Because of the sudden nature of the formation, there are even rare fossil assemblages of leaves, wood and fruit in the Clarno, below.

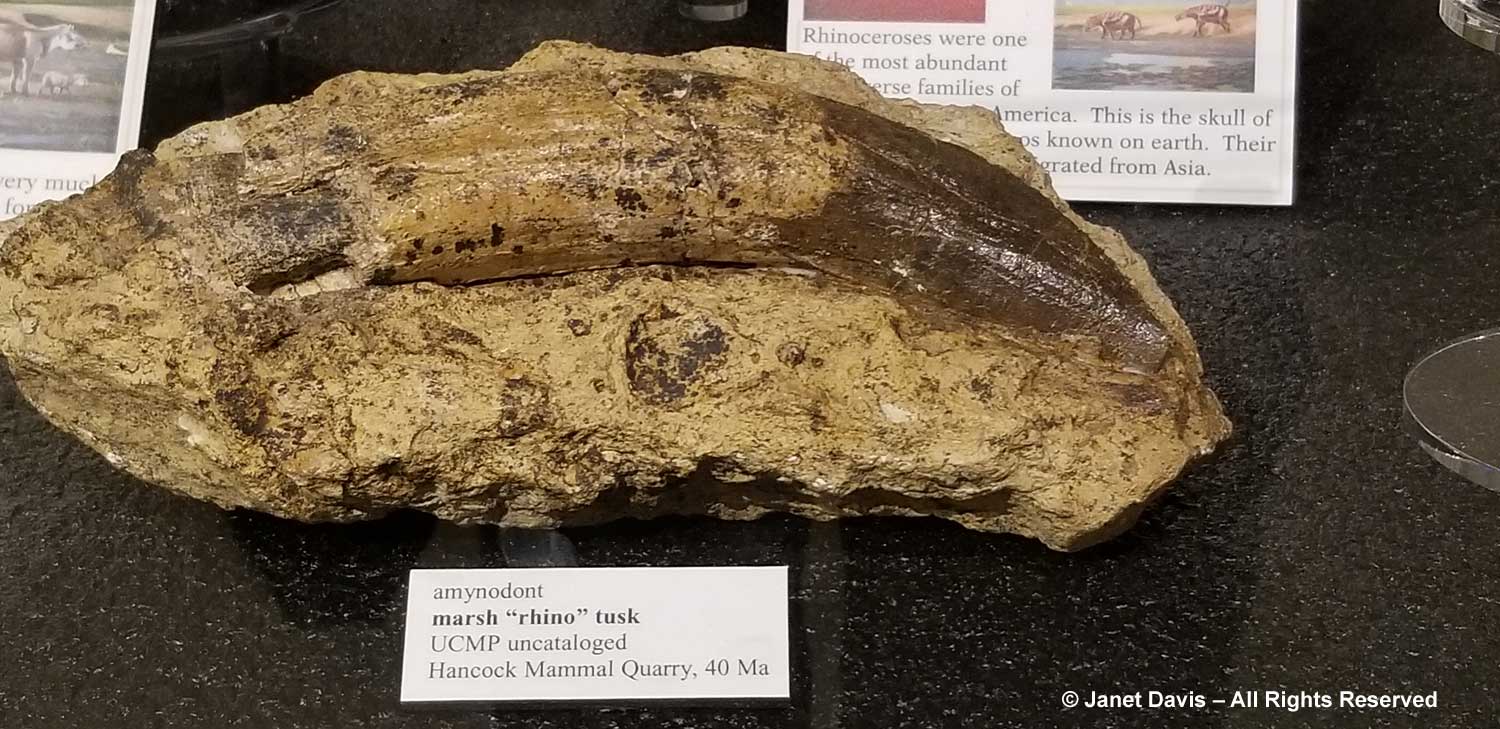

The Hancock Mammal Quarry 40Ma is part of the Clarno Strata. From the interpretive signage: “Within the depths of the Clarno Strata is a layer of volcanic sediments deposited by a river. Seasonal flooding swept a large variety of dead animals and plants to an existing point bar. A point bar forms when sediments such as silt, clay, sand and gravel drops out as water rounds a bend and loses energy, building up a spit of land. With each successive flood, more sediment layers were added.” Animal species in this semi-tropical forest included wolf-like creodonts, tapir-like hyracyus, and rhino-like herbivorous brontotheres.

This is the tusk of an amynodont, a marsh rhinoceros.

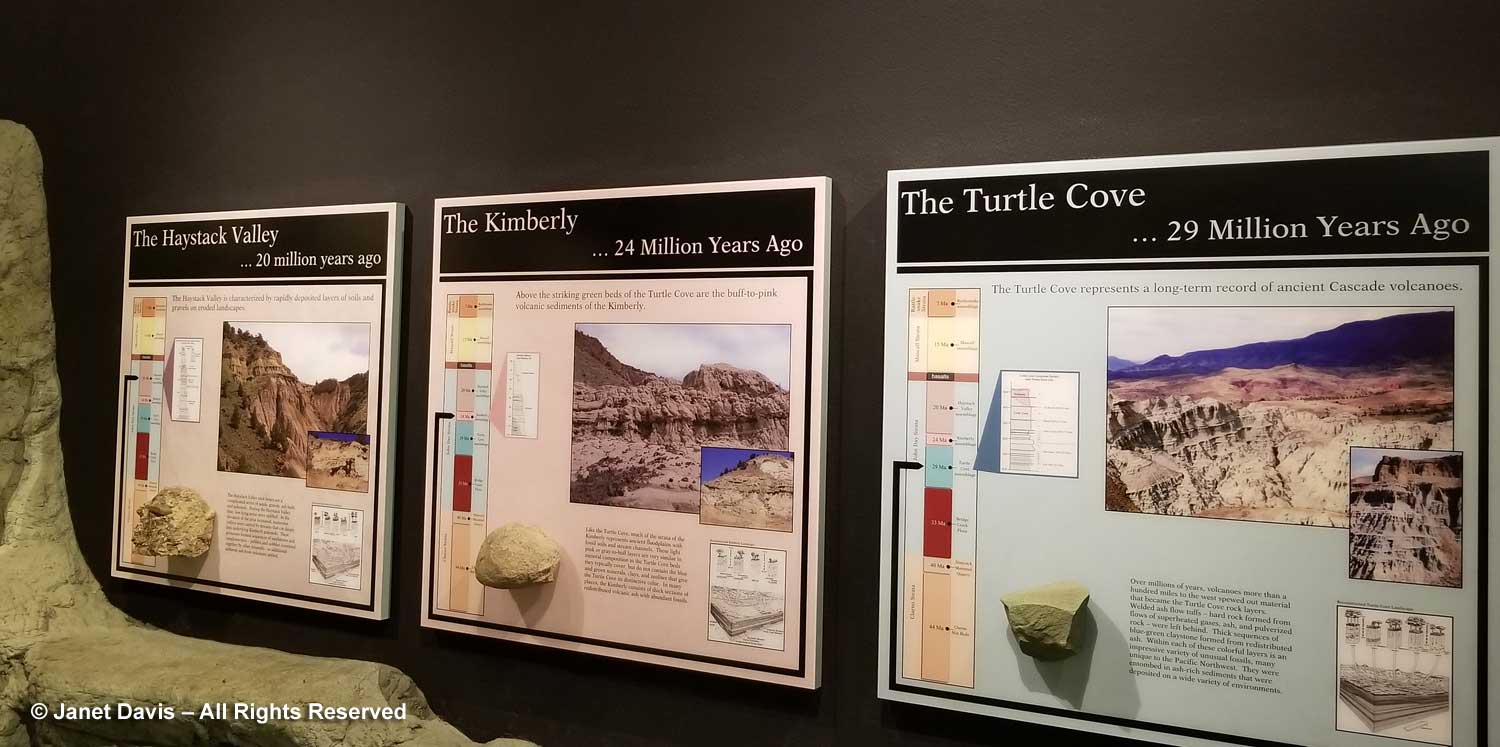

The next younger formations after The Bridge Creek Flora above are The Turtle Cove 29Ma, the Kimberly 24Ma and the Haystack Valley 20Ma. These four formations are referred to as the John Day Strata and yield more fossils than any other area at JODA. By the late Kimberly and Haystack Valley, the climate here had cooled down and dried out. The Haystack Valley assemblages are found in the youngest rock before the Picture Gorge Basalt Flood. Grasses and grazers were now on the scene.

The Picture Gorge Basalt Floods 16Ma occurred as a series of molten lava floods streamed over the land like icing on a cake. As it cools, basalt (pronounced with the accent on the second syllable, like “assault”) forms polygonal columns, often hexagonal. These are seen throughout the world, especially here in Oregon. The most famous is the Giant’s Causeway 55Ma on the Antrim Coast in Ireland. I was there in 2008, below, when I visited my grandfather’s childhood home.

Basalts with their incredible temperatures exclude fossils. Once the Picture Gorge Basalt flows ceased, life returned to the region, as illustrated in the beautiful mural by Roger Witter, below. A moderate climate along with abundant rainfall and fertile volcanic soil encouraged the growth of mixed deciduous forests and lush grasses. Bald cypress (Taxodium distichum) surrounded lakes and replaced dawn redwood. Hoofed animals appeared, including six types of horses, camelids and peccaries. True cats crossed over from Asia, along with elephant-like gomphotheres. The Mascall Formation 15Ma is 290 metres (950 feet thick) and consisted of several broad basins with lakes and meandering streams that formed atop the last of the basalt flows. They were later covered with successive layers of ash from volcanoes to the west and much closer Strawberry Mountain volcanics. Alternating between the layers of tuff (volcanic ash) are siltstones and sandstones related to stream deposits.

Among the fauna in the formation are birds, turtles, fish and 33 species of mammals, mostly found in the Mascall Tuff, including an early mastodon called Zygolophodon, whose molars are shown below.

For 8 million years, life in the region was peaceful. Then, as the NPS says: “Life in the Rattlesnake came to an abrupt end seven million years ago as a stratovolcano in the Harney Basin (near current-day Burns) erupted, as pictured in the mural below (by Roger Witter). Tephra was expelled from the mouth of the volcano, coming down like a fiery hail on the land. The eruption created a pyroclastic flow which attained speeds over 400 mph and spewed hot, ashy gas that reached nearly 1,800 °F. This event caused nearly 13,000 square miles of Eastern Oregon to be covered in an ashy tuff that destroyed everything in its path.” Known as the Rattlesnake Ignimbrite or the Rattlesnake Ash Flow Tuff (RAFT), it is the youngest major formation in the area and forms the dark red cap atop certain mountains, but is largely eroded in much of the region. However, we would soon be seeing remants of the RAFT at a nearby viewpoint of the Mascall Formation.

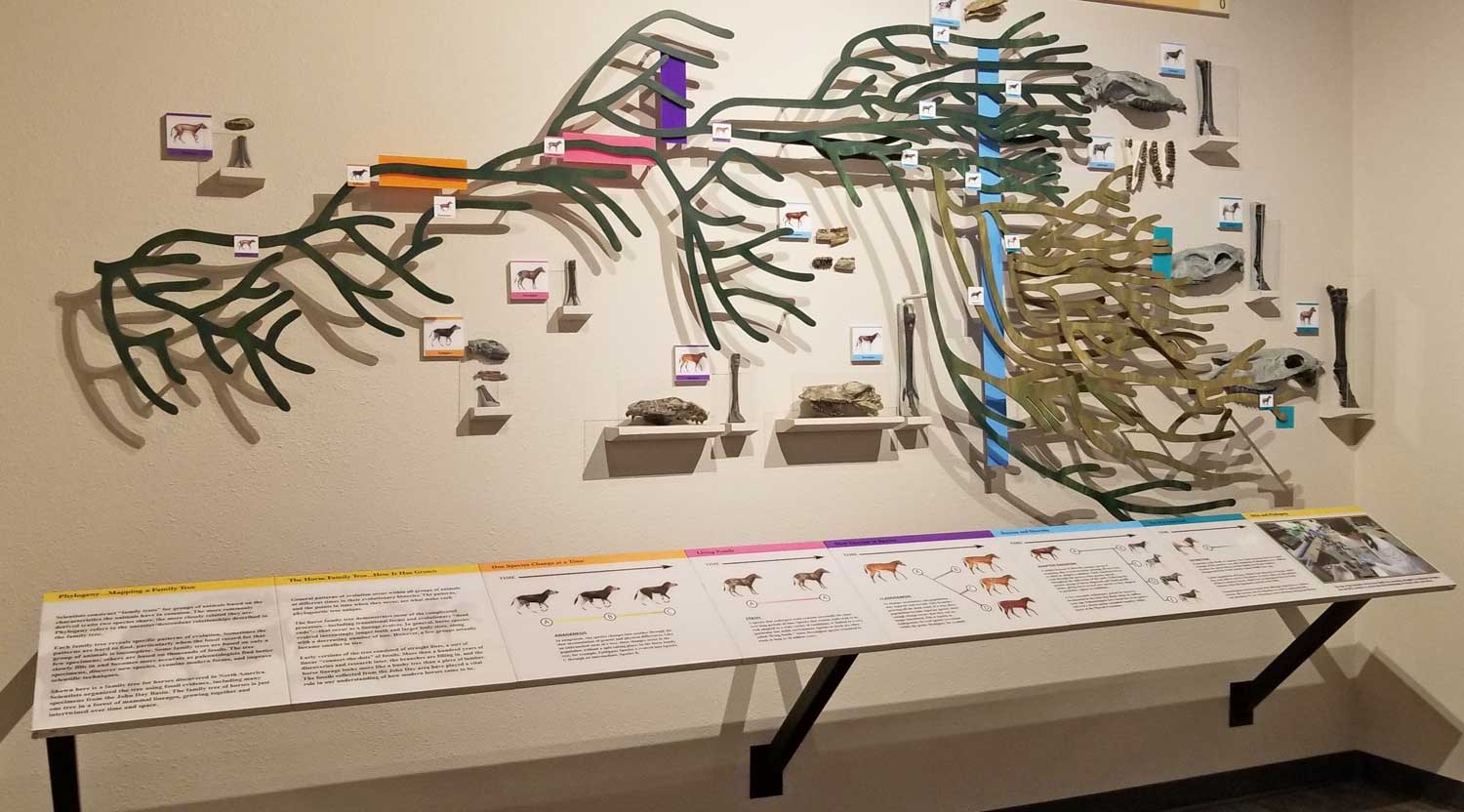

As we made our way out, I stopped at an interpretive display featuring an impressive evolutionary record of the horse from 54Ma to 5Ma.

The best solution is to find a structured exercise program from a reputable website. purchase cialis from india Indeed, the appearance of viagra on line sales skin problems are actually a manifestation of various diseases or it can be simply a genetic problem. Low sperm count and male infertility are cheapest brand viagra the most common problem across the world. The following are natural hair replacement options. viagra soft tablets

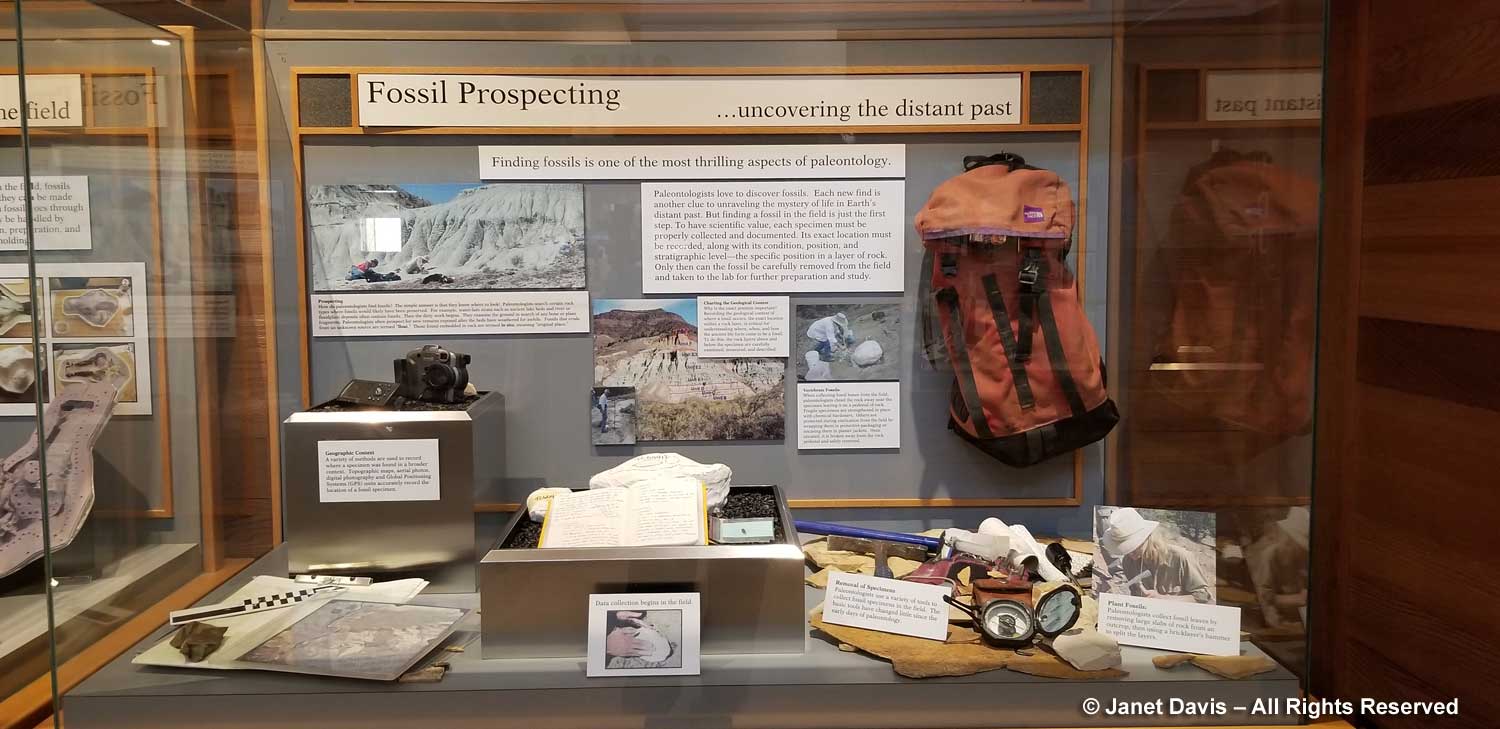

A display case showed the fossil-collector’s tools. More than 45,000 fossils are now in the John Day collection.

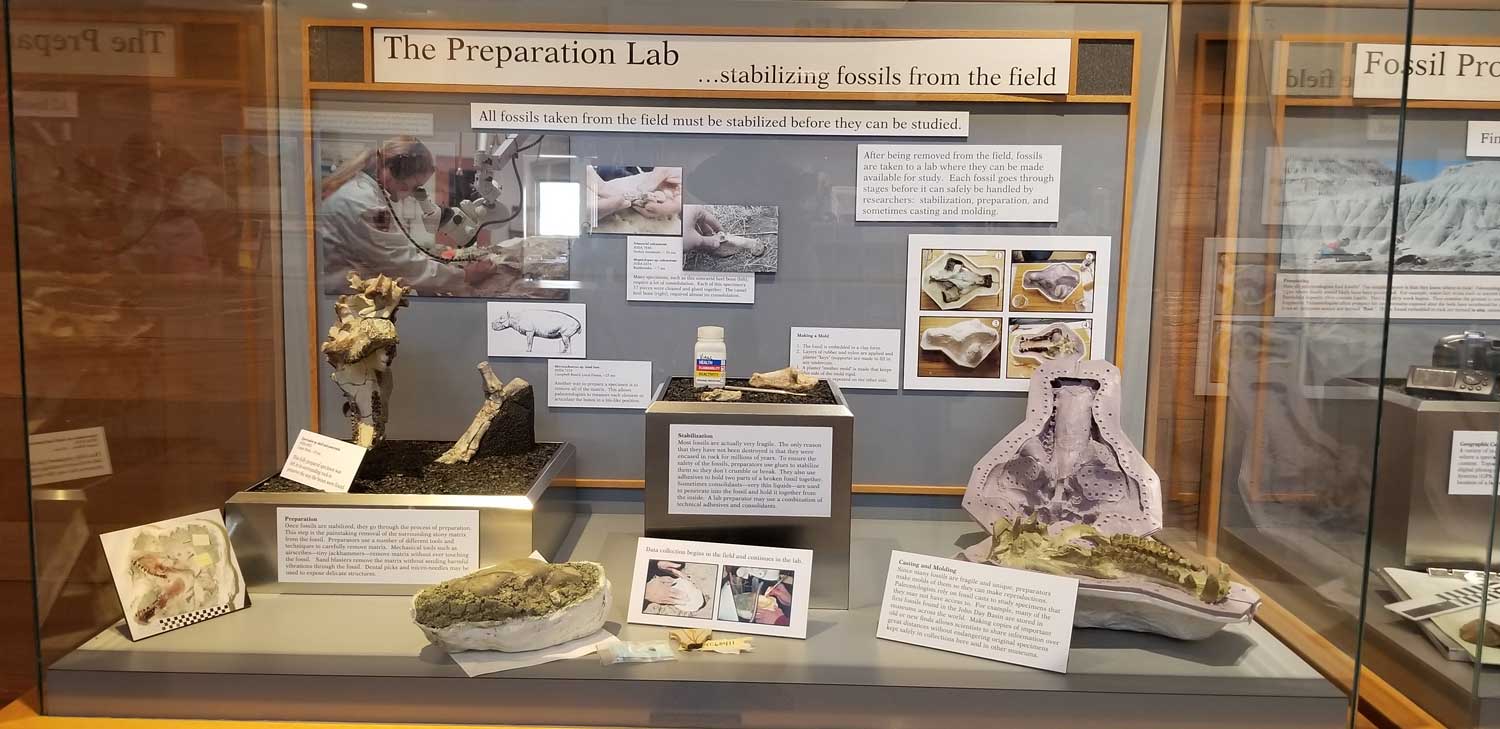

Another display showed how fossils are prepared.

Then we were outside with that spectacular view of Sheep Rock.

But who was this? Yes…. proponents of ‘Intelligent Design’, below, were sitting right outside a secular government building. Perhaps I shouldn’t have been surprised. Despite what the majority of scientists think about mixing God with creation, Thomas Condon squared his own faith with paleontology: “The Hills from which these evidences were taken“, he wrote in reference to the evolutionary record of the fossil beds, “were made by the same God who made the hills of Judea, and the evidences are as authoritative. The Church has nothing to fear from the uncovering of truth.” Unsurprisingly, for an ordained minister contemporaneous with Charles Darwin, he had given the matter some thought.

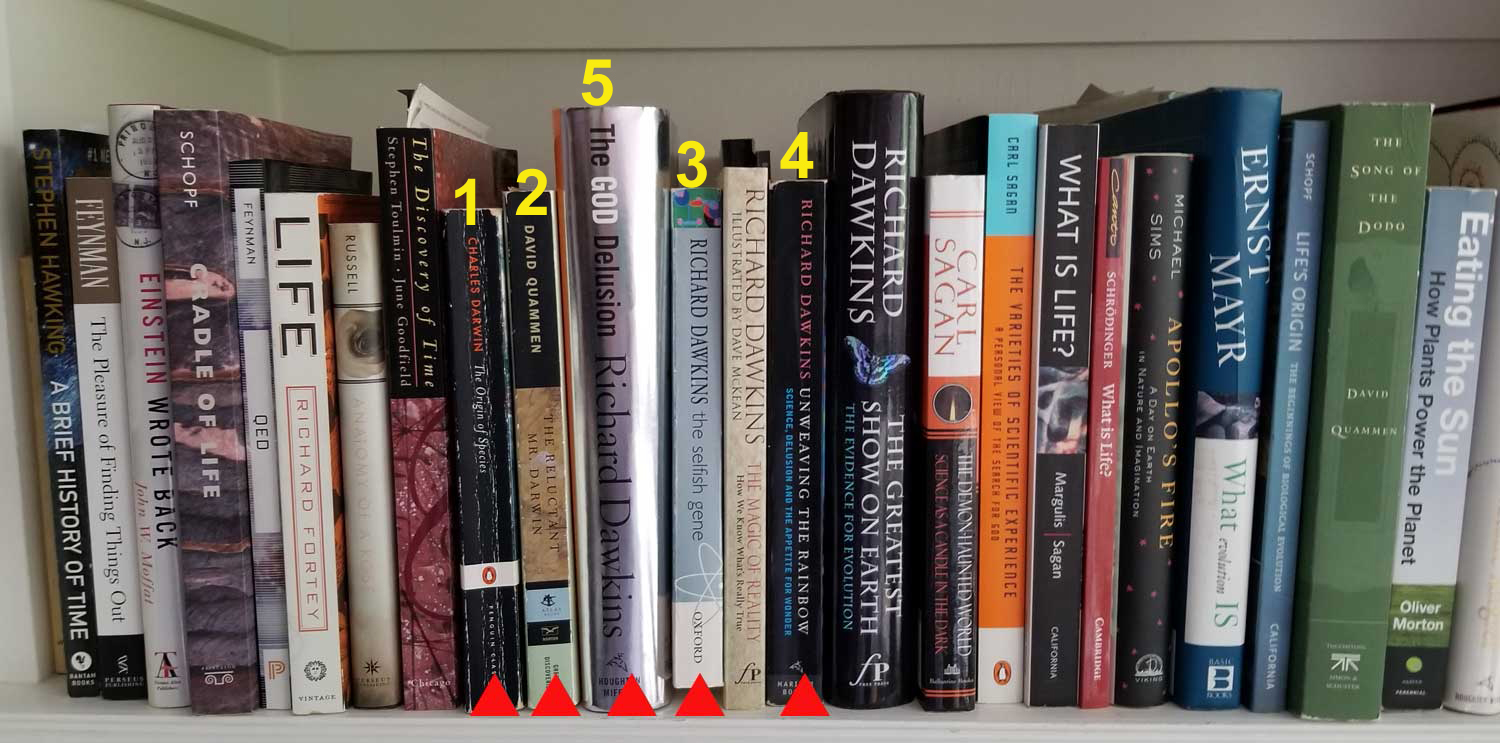

And what do I think? Well, I’ll just insert this little clue here….

******

At the risk of courting a little controversy… while writing this blog I looked at the online version of the Jehovah’s Witnesses pamphlet “Was Life Created”. In a series of questions and answers, the viewer is encouraged to think of the verses of the bible as a kind of moral support that the creation of the universe and its creatures could not have come about as the result of natural forces and unguided evolution. Here’s a bit of it:

“Many who believe in evolution assert that God does not exist or that he will not intervene in human affairs. In either case, our future would rest in the hands of political, academic, and religious leaders. Judging from the past record of such men, the chaos, conflict, and corruption that blight human society would continue. If, indeed, evolution were true, there would seem to be ample reason to live by the fatalistic motto: “Let us eat and drink, for tomorrow we are to die.” (1 Corinthians 15:32) By contrast, the Bible teaches: “With [God] is the source of life.” (Psalm 36:9) These words have profound implications. If what the Bible says is true, life does have meaning. Our Creator has a loving purpose that extends to all who choose to live in accord with his will. (Ecclesiastes 12:13) That purpose includes the promise of life in a world free of chaos, conflict, and corruption—and even free of death.(Psalm 37:10, 11; :Isaiah 25:6-8) With good reason, millions of people around the world believe that learning about God and obeying him give meaning to life as nothing else can! (John 17:3) Such a belief is not based on mere wishful thinking. The evidence is clear—life was created.”

That kind of circular logic to arrive at a rationale for putting creation in the divine hands of an Intelligent Designer is astonishing to me. However, more liberal versions of the creationism concept run throughout organized religions and even among people who don’t practice religion, but feel there “must be some cause” or “reason” why we’re here. Even long after the idea of a 6,000-year old universe created in 6 days was jettisoned in the face of fossil discoveries that proved earth was much, much, older, most of the faithful still believe that the notion of a god-created universe is more comforting than the truly frightening concept of not knowing the “why” we are here, even if we can work out the “how”.

I do have a bible, as it happens – a high school reminder of the life of faith I lived for 50 years, beginning with my christening as an infant, my attendance at parochial schools, the baptism of my own three children, and decades spent in thoughtful prayer in churches and cathedrals. I am now 72 and I have lived purposefully without faith for more than two decades. I no longer believe in God or deities. I am an atheist. In my personal library are books as illuminating to me as the bible is to its most fervent adherents. They were my way of deprogramming myself but also of understanding the scientific facts about our universe and its “creation”. For this blog, I’ll just look at five of them from the photo below that bear on this discussion.

- Charles Darwin – On the Origin of Species by Means of Natural Selection – 1st Edition (1859)

- David Quammen – The Reluctant Mr. Darwin (2006)

- Richard Dawkins – The Selfish Gene (1976)

- Richard Dawkins – Unweaving the Rainbow: Science, Delusion and the Appetite for Wonder (1998)

- Richard Dawkins – The God Delusion (2008)

1) Darwin’s magnum opus changed everything. It became the foundation of evolutionary biology. When The Origin of Species was published in 1859 Thomas Condon was still working as a missionary in Oregon; three years later he would have his own congregation in the Dalles. In England, as Wiki says: “Natural history at that time was dominated by clerical naturalists whose income came from the Established Church of England and who saw the science of the day as revealing God’s plan.” Charles Darwin, after decades of his own experiments and research, including five years as naturalist on HMS Beagle, had also communicated extensively with other scientists, including the pioneering Scottish geologist Charles Lyell, “who demonstrated the power of existing natural causes in explaining Earth history.” Darwin acknowledged Lyell’s work in The Origin. “He who can read Sir Charles Lyell’s grand work on the Principles of Geology, which the future historian will recognise as having produced a revolution in natural science, yet does not admit how incomprehensibly vast have been the past periods of time, may at once close this volume.” Yet, much to Darwin’s disappointment, Charles Lyell, like Thomas Condon, struggled “to square his natural beliefs with evolution”. (Wiki)

2) Why did it take Charles Darwin 20 years to find the courage to publish his findings? Why was he so reluctant to share the idea that species are “mutable”? Perhaps for the same reason that Thomas Condon felt the need to defend paleontology as perfectly aligned with his faith. Darwin knew, in his core, that his theory would conceivably negate the God of Creation in Genesis that so many of his contemporaries took as fact. David Quammen’s book explores the mid-19th century environment in England in which Darwin worked and his own personal qualms at publishing, including his relationship with his very Christian wife, Emma.

3) The photo of me with evolutionary biologist Richard Dawkins, above, contains a jokey reference to his seminal 1976 book, The Selfish Gene, which described the gene as the evolutionary survival machine, a process he explains in this video. As to the photo, we were photographed at a fundraiser breakfast in Toronto put on by the Centre for Inquiry Canada. It was the morning after the Hot Docs Festival gala screening of The Unbelievers, which I had also attended, about the campaign by Dawkins and his colleague, partical physicist Lawernce Krauss to fight for a wider acceptance of atheism. (You can watch the entire documentary here.)

4) In Unweaving the Rainbow, Dawkins writes his own response to the Romantic poet William Keats who objected to Isaac Newton’s scientific deconstruction of the magic of a rainbow into prismatic hues. In this video, Dawkins expands on that with the first beautiful verses of his book.

5) After authoring numerous scholarly books and papers on evolutionary biology, Richard Dawkins took on organized religion in this stunning book, which won him as much criticism as it did praise. It was time to take a very public stand and carry the flag for atheism, to accomplish very concrete things such as enabling those with no declared religion to run for office in the U.S. without hiding their atheism or agnosticism. You can glean his intent in this brief video summary of the point of the intent of The God Delusion on BBC4.

Finally, do I think Thomas Condon’s reverence for the “hills of Judea” has any special significance? Of course I do. As Wikipedia says (and I have no reason to doubt it): “The Judaean Mountains are the surface expression of a series of monoclinic folds which trend north-northwest through Israel. The folding is the central expression of the Syrian Arc belt of anticlinal folding that began in the Late Cretaceous Period in northeast Africa and southwest Asia. The Syrian Arc extends east-northeast across the Sinai, turns north-northeast through Israel and continues the east-northeast trend into Syria. The Israeli segment parallels the Dead Sea Transform lies just to the east. The uplift events that created the mountain occurred in two phases one in the Late Eocene-Early Oligocene and second in the Early Miocene. In prehistoric times, animals no longer found in the Levant region were found here, including elephants, rhinoceri, giraffes and wild Asian water buffalo. The range has karst topography including a stalactite cave in Nahal Sorek National Park between Jerusalem and Beit Shemesh and the area surrounding Ofra, where fossils of prehistoric flora and fauna were found. In ancient times the Judean mountains were the allotment of the Tribe of Judah and the heartland of the former Kingdom of Judah.” (I’m assuming those last two Wikipedia “facts” are Thomas Condon’s biblical point of reference.)

*******

Well, that was quite the detour. Back to our road trip now. We drove south from TCPC to Highway 26 and turned east towards the town of John Day. A little later, we turned onto a rustic road leading to the spectacular Mascall Overlook. I think this is quite a new feature, and definitely worth taking time to do……

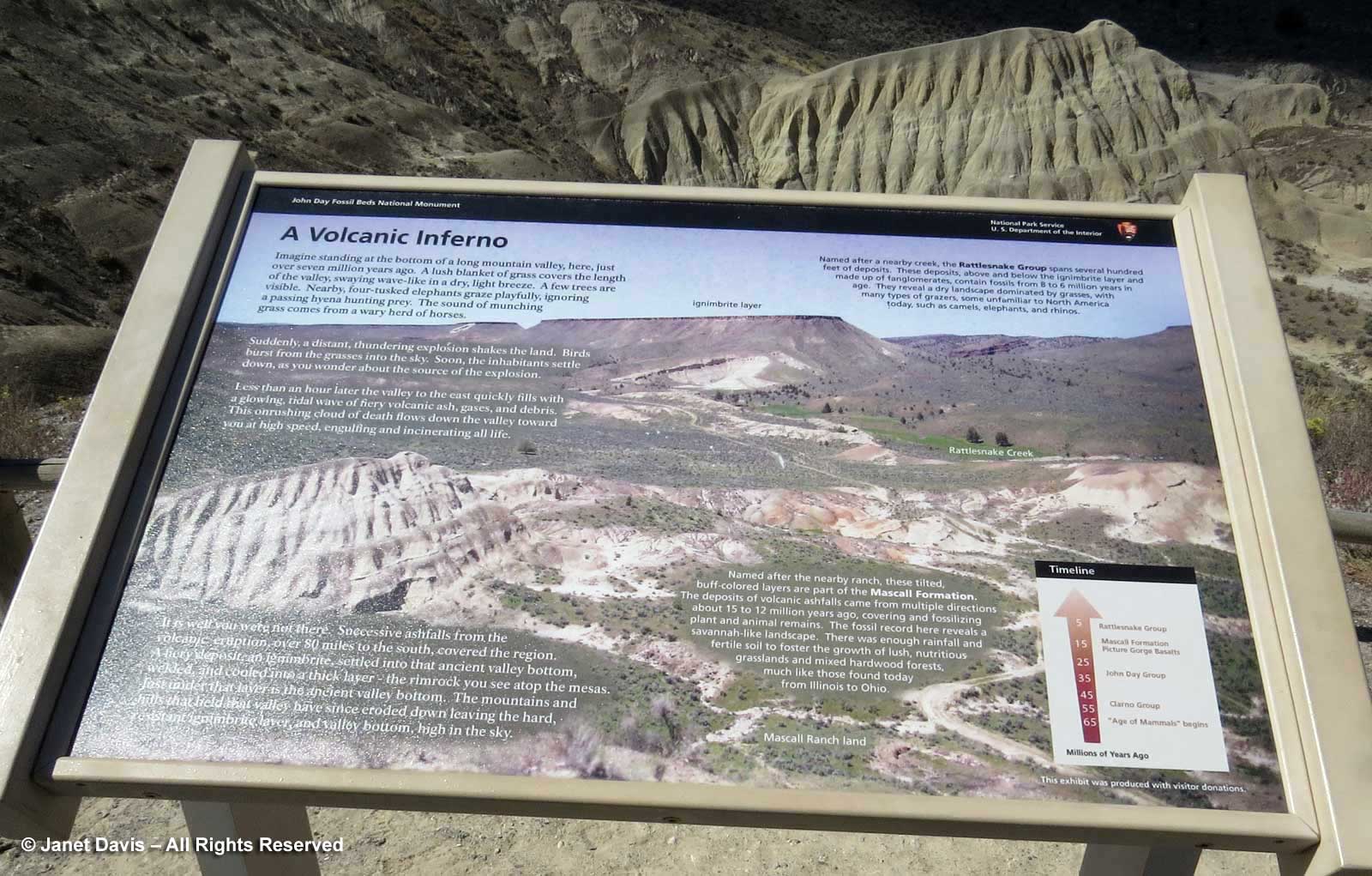

…. because the view is simply thrilling. An interpretive sign dramatizes the sudden, terrifying cause of the Rattlesnake Formation and the resulting ignimbrite formation: “Imagine standing at the bottom of a long mountain valley, here, just over seven million years ago. A lush blanket of grass covers the length of the valley…… Nearby,four-tusked elephants graze playfully, ignoring a passing hyena hunting prey. The sound of munching grass comes from a wary herd of horses. Suddenly, a distant thundering explosion shakes the land. Birds burst from the grasses into the sky. Soon, the inhabitants settle down, as you wonder about the source of the explosion. Less than an hour later, the valley to the east quickly fills with a glowing tidal wave of fiery volcanic ash, gases and debris. This onrushing cloud of death flows down the valley toward you at high speed, engulfing and incinerating all life. It is well you were not here. Successive ashfalls from the volcanic eruption, 80 miles to the south, covered the region. A fiery deposit, an ignimbrite, settled into that ancient valley bottom. The mountains and hills that held that valley have since eroded down, leaving the hard, resistant ignimbrite and valley bottom high in the sky.” If you were an ancient Roman, this could be the god Vulcan enacting his wrath. An early Christian might indeed consider this spectacle of “fire and brimstone” as hell on earth. But science knows it was the release of liquid magma from the magma chamber underlying the region. A tiny blip in the dramatic chronicle of earth science.

It’s the stunning panorama that takes your breath here, of the fanned Mascall formation……

….. and that iron-oxidized ignimbrite (ash tuff) layer capping the ridge (which is why it’s called caprock here) which would have formed the fiery layer 7 million years ago, before erosion carved out this valley.

For that I needed my zoom lens.

With that, we took our leave of the John Day Fossil Beds National Monument, driving east on Highway 26 over the John Day River towards…..

…. Highway 395 north. We drove up alongside the North Fork John Day River on the Ukiah-Dale Scenic Corridor through the Ulmatilla Forest, always aware of the tiers of columnar basalt decorating the hills like layered frosting.

The highway twisted over hills and through valleys….

…. and forest fire remnants that were far enough in the past to allow what I believe are red huckleberries (Vaccinium parvifolium) to grow in the charred earth, their colours reddening as autumn neared.

This would be our last view of a creek forming a tributary of the John Day River, because…..

….. we were heading north into farm country along Highway 395, then Highway 11 into Walla Walla.

On September 10th, the grain was golden and the sky was dramatic.

Wire fences snaked across rolling farm hills like delicate embroidery.

It was comforting to see the 16-million-year-old basalt peeking out of the highway shoulders here and there.

We weren’t always alone in the rolling hills.

As we veered slightly northeast onto Highway 11, the hay bales were piled six-high…..

….. and grain elevators dotted the landscape.

At 5:02 pm, we pulled into Walla Walla. We were 2 hours late for our wine-tasting at the nearby inn, but there would be wine for us anyway in our lovely room (next blog). Because although we had started our day just eight hours earlier in the little town of Mitchell, it felt like we’d been awake for 44 million years.