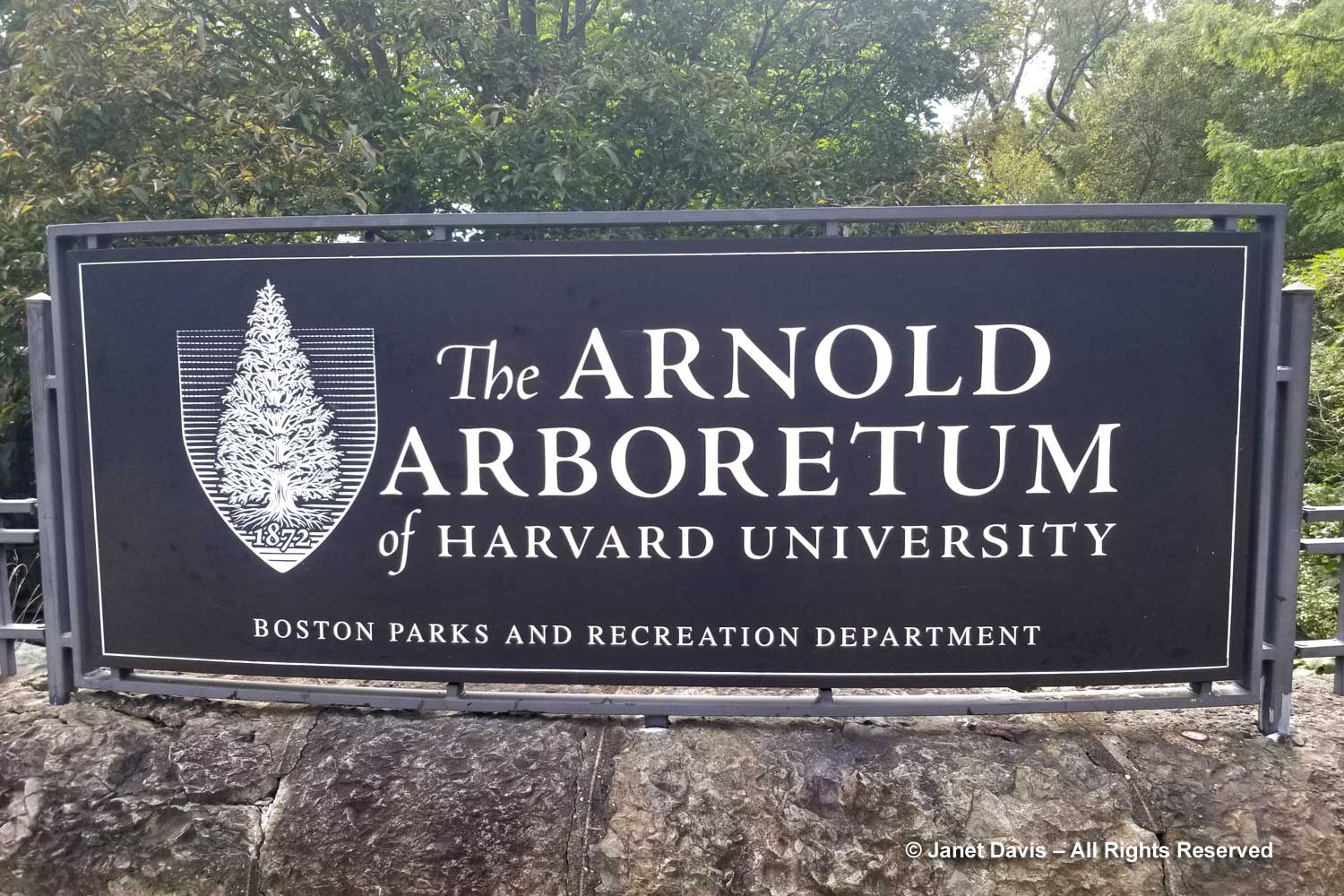

At 281 acres (113 hectares), Boston’s Arnold Arboretum is not the kind of place you waltz through in a few hours. (And this is not the kind of blog you waltz through quickly – unless you’re a plant geek like me. Fair warning.)

So when we arrived on Sunday, October 8th after driving from New Hampshire, braving Boston’s famous traffic and entering the garden via the Walter Street gate and Peters Hill, we knew we wouldn’t be seeing much of it that day. Fortunately, we would return on Monday morning and enter from the main Arborway Gate – and I’ve put both entrances on the garden map below.

Unlike the rest of the arboretum, Peters Hill – which is a “drumlin” in geological terms, a hill comprised of glacial till deposited as the glaciers retreated around 12,000 years ago and the third highest hill in Boston – also features a meadow, which in October was mostly native asters and non-native Queen Anne’s lace.

But I was aiming at Peters Hill because it has the arboretum’s collection of crabapples, hawthorns and mountain ash trees, among other species – and I knew they would be in fruit now. It was an opportunity to find one of my favourite crabapples, Sargent’s crabapple, or Malus sargentii, a beautiful, dwarf species covered in May with white blossoms and buzzing bees. It was named by the Arnold’s resident taxonomist and dendrologist, German-born Alfred Rehder (1863-1949), in honour of…..

….the Arnold Arboretum’s first director Charles Sprague Sargent (1841-1927), who collected seed of the small tree in a salt marsh in Japan in 1892. He also collected seed of a cherry on that trip which, though other botanists had previously classified it as different species, would also be named for him, Prunus sargentii, Japanese hill cherry or Sargent’s cherry. Charles Sargent had graduated from Harvard College in Biology in 1862, served with the Union Army during the Civil War, then returned to his wealthy family’s 130-acre Brookline estate to manage its landscape. When Harvard decided to establish an arboretum in 1872, he was appointed its director, a position he held for 55 years until his death. The photo below was made in 1901 when he was 60. In reading the memorial written by Arnold taxonomist Alfred Rehder in 1927, one gains a sense of the immense size of Charles Sargent’s accomplishments, at the Arnold, in the native sylva of North America, and throughout the world in the plants he himself collected and those collected under his supervision.

Perhaps the Arnold’s most renowned personality is Ernest Henry “Chinese” Wilson (1876-1930). Born in Chipping Camden, Gloucestershire, he was travelling to San Francisco from New York by train in spring 1899 on his first Chinese plant collecting trip for James Veitch & Sons nursery in England when he visited the Arnold Arboretum for five days with a letter of introduction to Charles Sargent, in order to learn their techniques for preserving shipped plants and seeds. On his second trip for Veitch’s in 1903, he collected the regal lily (L. regale). But he had so impressed Charles Sargent that he was offered a job in 1906 doing plant exploration for the Arnold, with journeys to China made in 1907, 1908 and 1910; one to Japan in 1911-16 for cultivated cherries and azaleas; Korea and Formosa in 1917-18; and New Zealand, India, Central and South America in 1922-24 to establish connections with botanical gardens and explore southern gymnosperms. He was Assistant Director of the Arnold from 1919-27, and following Charles Sargent’s death in 1927, Wilson assumed the role of Keeper of the Arboretum. A skilled story-teller, he also wrote hundreds of articles and several books. He died in 1930 at the age of 54 along with his wife in a tragic car accident in Massachusetts while returning from a visit to their daughter in upstate New York.

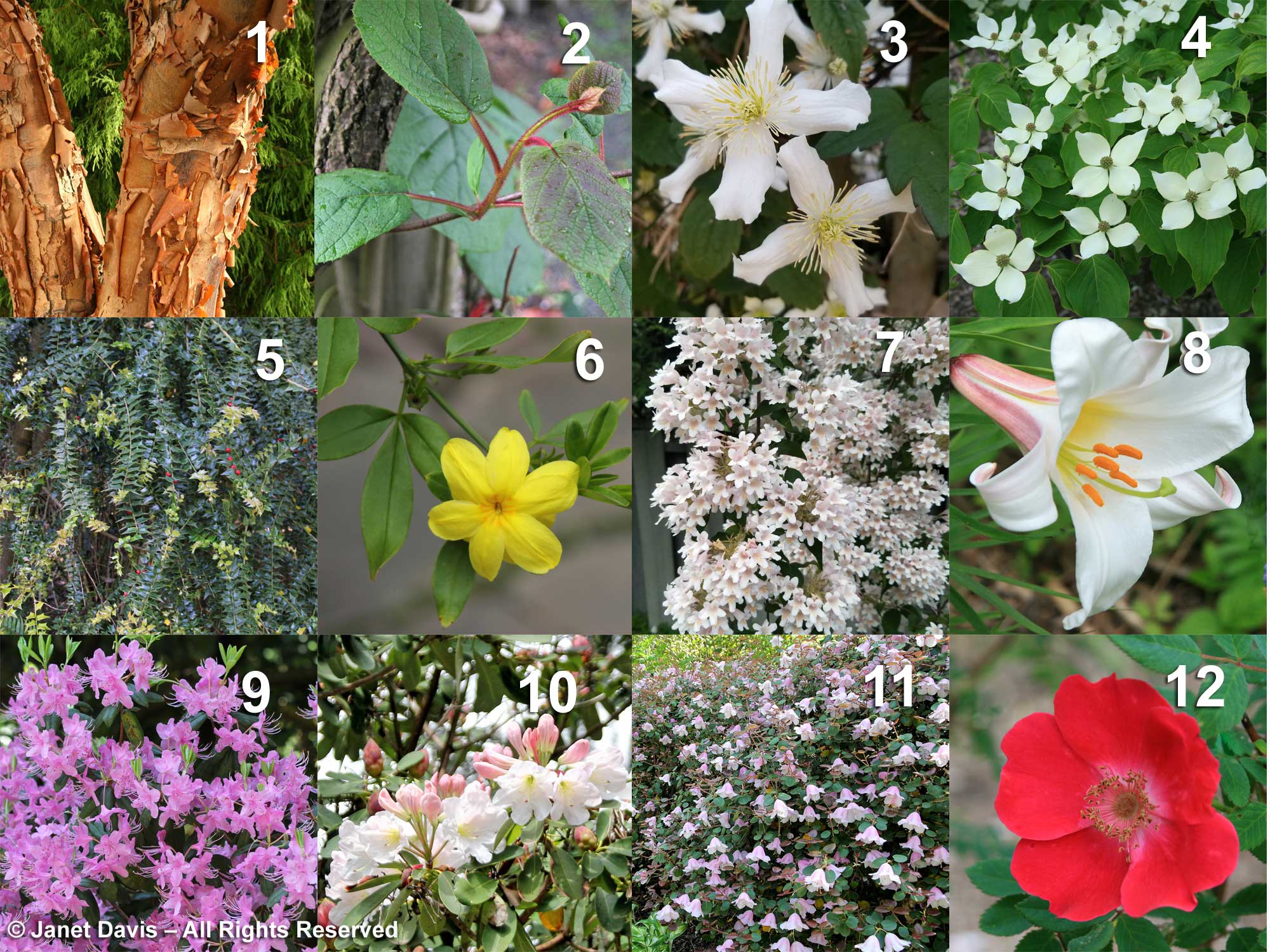

Below are just a dozen of the 2,000 species Wilson is credited with introducing to the western world. Others include Stewartia sinensis and Malus hupehensis.

I wanted to have a look at the fruit of the crabapple species on Peters Hill, although summer’s abundant rain had resulted in considerable apple blight on the leaves. Below is Malus ‘Golden Hornet’….

….. and Malus ‘David’….

…. and the tiny yellow fruit of Malus x robusta var. xanthocarpa (Malus baccata x M. prunifolia).

Charles Sargent was especially interested in hawthorns, and the hawthorn collection also resides on Peters Hill, including cockspur thorn (Crataegus crus-galli) with its vicious thorns.

Sorbus commixta is sometimes called the Japanese rowan; its orange fruit is as attractive as its spring flowers.

One of my favourite small Sorbus species is Korean mountain ash, S. alnifolia. It was covered with tiny, salmon-pink fruit.

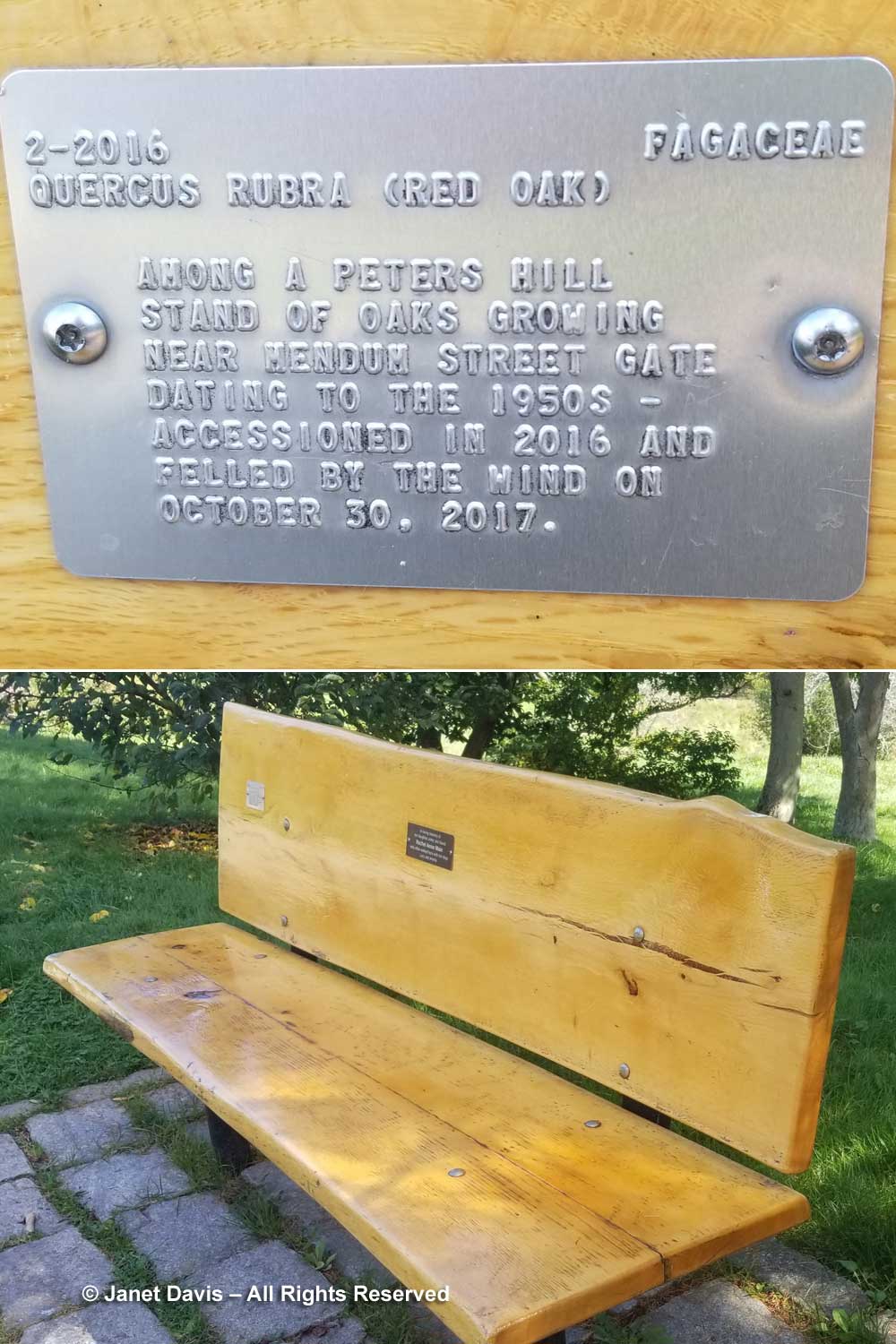

Tired from our long driving day and walk, we sat on a bench on Peters Hill. I loved that the Arnold turns fallen trees into these handsome benches – this one was a red oak (Quercus rubra) that blew down in a windstorm on October 30, 2017 that left 1.5 million people without power.

As we circled Peters Hill to head out and drive to our hotel in nearby Dedham, we came upon a hive of activity marking the Arnold’s “Second Sunday” event, one of three offered in late summer/early autumn 2023. According to the website, these days “reflect an institutional value to expand our welcome and outreach to all surrounding neighborhoods, especially those that have received less attention in the past. The events offer visitors opportunities to learn more about Peters Hill as well as venture into other areas of our landscape that lie off the beaten path”. Arnold intern Zach Shein, below, was manning one of the booths and showing off some of the arboretum’s “spooky plants” in time for Halloween.

Here were a few of his samples, clockwise from upper left: poison ivy (Rhus radicans); trifoliate orange (Citrus trifoliata); castor bean (Ricinus communis); and autumn monkshood (Aconitum carmichaelii Arendsii Group).

Nearby, Arnold evolutionary biologist Anna Feller was explaining her research on the reproductive strategies of Phlox paniculata to interested visitors. Then it was time to find our hotel for the night in nearby Dedbury.

*****

The next morning, refreshed, we returned to the Arnold’s main gate for a longer visit. Since it was Indigenous Peoples Day, the Hunnewell Visitor Center (1892) was closed. But we wanted to be outside anyway here at North America’s first public arboretum. A National Historic Landmark, the Arnold Arboretum is owned by the City of Boston and managed by Harvard University under a 1,000-year lease signed in 1882. It is a major part of the Emerald Necklace, a 7-mile network of parks and green spaces laid out by landscape architect Frederick Law Olmsted for the Boston Parks Department between 1878 and 1896. As a city park, it is free to all.

In an arboretum, one expects to find native plants like tuliptree, but I was interested in the tree below, Liriodendron x sinoamericanum, a hybrid of the American and Chinese species.

I stood under the pagoda or giant dogwood (Cornus controversa) from Asia to admire the beautiful symmetry of its foliage. This species and my favourite native shrub, Cornus alternifolia (I grow five in my garden), are the only dogwoods with alternate leaves.

Black tupelo (Nyssa sylvatica) is one of the last deciduous trees to turn colour, usually bright gold-to-red, before losing its leaves.

I’ve photographed a lot of lindens, but this was my first Amur linden (Tilia amurensis).

Trifoliate orange (Citrus trifoliata) is a hardy member of the citrus family, Rutaceae. Although very seedy, the fruits are edible, but bitter (good for marmalade, I hear) – and the wicked thorns are an effective deterrent to herbivory.

We came to the Leventritt Shrub & Vine Garden and spent time strolling through this 3-acre collection.

Flowering dogwood (Cornus florida) leaves were changing colour and the fruit had already been sampled by birds.

I liked the deep-wine fall colour of this smooth arrowwood viburnum (Viburnum recognitum), a native northeast shrub previously unknown to me. But the great surprise came when I looked at the plant label, for it had been sourced in 1968 from the Dominion Arboretum in Ottawa, specifically from L.C. Sherk. Larry became a friend of mine decades later when he was chief horticulturist for an Ontario nursery chain.

The goldenrain tree (Koelreuteria paniculata) gets its common name for its yellow flowers, but in late summer it develops interesting capsule fruit, below, which are rose-colored before turning brown. This tree is ‘Rose Lantern’.

I had never seen Isodon henryi before, but was interested to read that its unique properties makes it a “frost flower” on certain wintry days.

Walking under the vines arrayed neatly on the rows of steel trellises in the garden, I looked up to see the backlit leaves and prickly stems of Smilax sieboldii from Asia, and thought how apropos is the common name of members of this genus: greenbriar”.

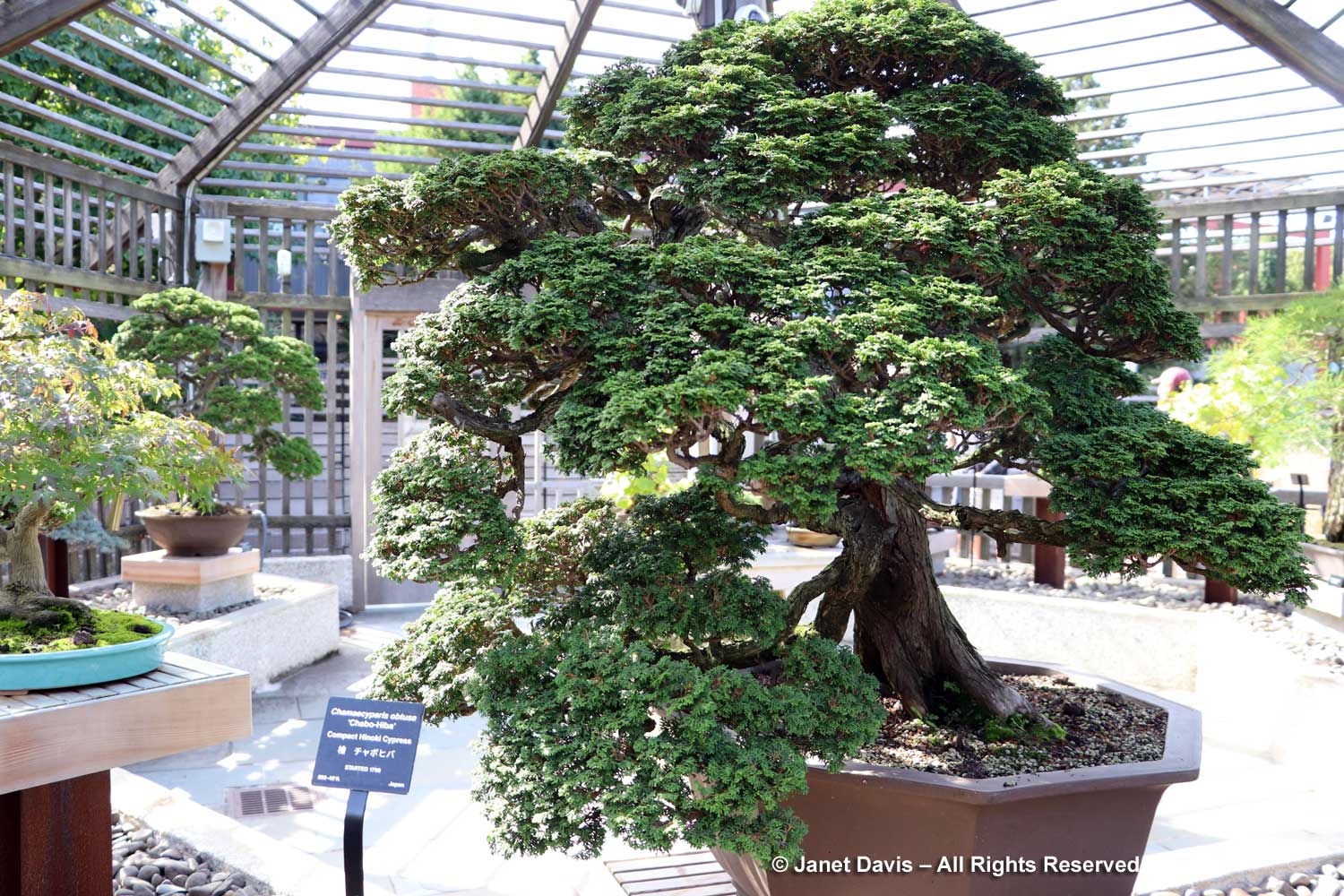

Next up was the Arnold’s Bonsai & Penjing exhibit. It is amazing to think that this Hinoki cypress (Chamaecyparis obtusa ‘Chabo-Hiba’), acquired in 1937 by the Arnold as part of former American Ambassador to Japan Larz Anderson’s Collection of Japanese Dwarfed Trees, actually germinated in 1799.

Smooth cranberry bush viburnum (V. opulus var. calvescens), a European species, bore clusters of red fruit very similar to native N. American highbush cranberry.

…. while the large Asian shrub sapphire-berry (Symplocos paniculata) was attracting lots of admirers with its brilliant blue fruit.

Not to be outdone, Japanese beautyberry (Callicarpa japonica ‘Leucocarpa’) bore its white autumn fruit like a pearl cluster necklace.

Sometimes, as a plant photographer, I forget to see the forest for the trees, so I took a moment here to gaze across the Bussey Hill landscape with its remarkable collection of towering trees and fruiting shrubs. Throughout the arboretum, visitors were enjoying the warm fall weather and I saw many families engaging their kids in the natural world. What a gift is the Arnold Arboretum to the people of Boston.

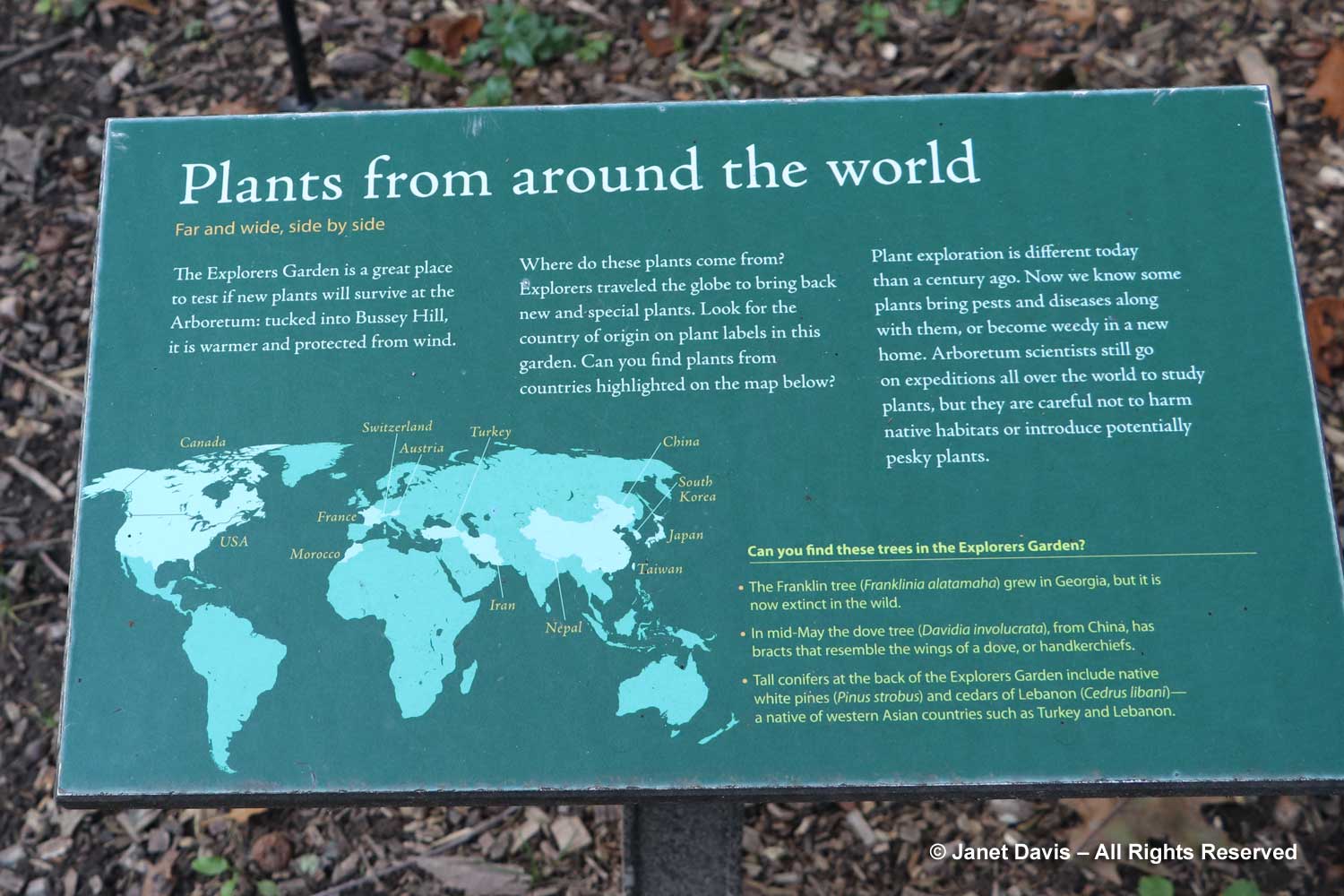

Then we headed up to the Explorers Garden….

…. and took the Chinese path to climb the hill. (This signage reminded me of the wonderful David Lam Asian Garden at the University of British Columbia Botanical Garden, where various path signs are named after explorers like von Siebold, Fortune, Forrest, Henry, Kingdon Ward and yes, the Wilson Glade. This is my blog on that fabulous garden.)

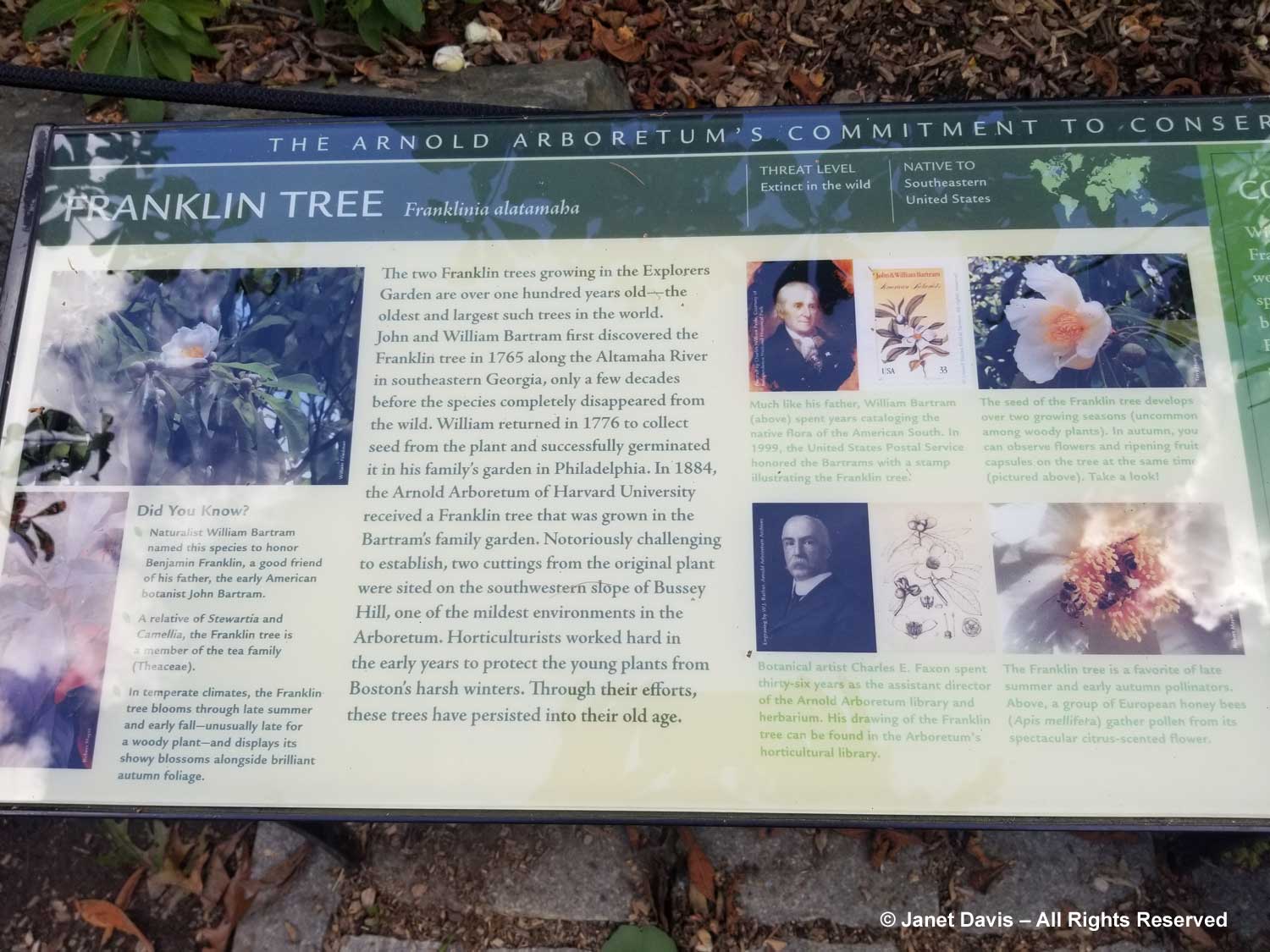

In the Explorers Garden we found the two oldest Franklin trees (Franklinia alatamaha) in the world, still bearing a few beautiful, perfumed, white blossoms, below. Naturalist William Bartram (1729-1823) named this tree, which he grew from seed he collected in 1776 from a small, relict population growing along the banks of the Altamaha River in coastal Georgia. He named it to honor Benjamin Franklin, a good friend of his father, the American botanist and early plant explorer John Bartram (1699-1777), with whom William had first seen the tree 11 years earlier. (Franklin, of course, helped draft the Declaration of Independence and the American Constitution and is featured on the American $100 bill.) The specific epithet refers to an alternative historic name of the river. There are no longer Franklin trees growing in the wild; it is believed that the trees the Bartrams found were glacial survivors on their way to extinction.

The interpretive sign includes information on the species. A relative of Stewartia and Camellia, the Franklin tree is a member of the tea family, Theaceae. In temperate regions, it blooms in September and October, unusually late for a woody plant, and displays its fragrant flowers alongside showy autumn foliage. The two Franklin trees growing in the Arnold Arboretum’s garden are the oldest and largest such trees in the world. They came from 1905 cuttings of a tree grown in Bartram’s Philadelphia garden that had sent to the Arnold in 1884.

They sprawl like giant shrubs, rooting themselves wherever their branches make contact with the ground. Now widely available in commerce, Franklin tree is difficult to establish, preferring sandy, acidic soil that remains consistently moist. Today, the species itself is kept alive through cultivation in gardens.

Moving on, we came to Chinese fringetree (Chionanthus retusus) with handsome blue fruit.

Seven-son-flower (Heptacodium miconioides), so named for the seven small, white flowers in each cluster, was now showing off its bright red calyces or sepals. This autumn show and the bee-friendly September flowers are highlights of this large, sprawling shrub. According to Gary Koller, writing for the Arnold, Henry ‘Chinese’ Wilson “collected the plant at Hsing-shan in western Hupeh (Hubei) province, China (Collection Number 2232). He made two collections of it, one in July and the other in October 1907, from cliffs at nine hundred meters (about three thousand feet) above sea level, where it was rare. In examining the herbarium specimens, Rehder (the Arnold’s taxonomist) found ‘that only a single ripe fruit was available for examination,’ which probably explains why no living plants resulted from that expedition. Rehder named the plant Heptacodium miconioides.” It would not be until the 1980 Sino-American Botanical Expedition, in which the Arnold’s Steven Spongberg participated, when seed obtained from a shrub growing in the Hangzhou Botanical Garden was brought back to the U.S. that seven-son-flower would be grown in North America.

Another species growing in the Explorers Garden from seed collected by the Sino-American Botanical Expedition is a mountain-ash-like tree called Yu’s whitebeam, Alniaria yuana (formerly Sorbus), with plump, shiny fruit.

As we headed back towards our car, we passed the Euonymus collection, all in fruit, including the pink capsules of flat-stalked spindle (E. planipes), with the orange fruit still to be revealed. It was labelled E. sachalinense, but I believe that name has been changed, according to sources online.

I was also pleased to see the fruiting habit of a plant I know from the collection at my local Mount Pleasant Cemetery, Oriental photinia (P. villosa var. villosa). I even included it in a blog called June Whites. But you can see that the leaves on this species, as well as most of the Malus, Crataegus and other members of the Rosaceae family, were afflicted with disease, likely fire blight, after a very wet spring/summer in 2023.

I heard the clip-clop of a horse and looking at the road was greeted with the smile of a passing Boston Park Ranger. Mounted rangers patrol the arboretum and other parks in the Green Necklace.

We took a different road towards the exit than the one on which we’d entered three-and-a-half hours earlier; that brought us close to one of the Arnold’s three ponds. Originally maintained as decorative features, recent restoration has resulted in a naturalistic habitat for aquatic wildlife and plants, including the bald cypress at left. It felt like the perfect ecological bookend to the historic Hunnewell Building where we’d begun our visit, on this fine October day.

*****

If you’re planning a garden trip to New England, I highly recommend Jana Milbocker’s excellent ‘The Garden Tourist’s New England‘, featuring 140 private and public gardens and nurseries. It’s available on her website Enchanted Gardens.