At this point in a Toronto winter, with loads of snow remaining on the ground and most days still well below freezing, it is such a joy to watch the bird life in my garden. There isn’t the chirpy avian soundtrack of spring, not yet, but the flash of cardinals zooming at full speed right into their nest in the big cedar hedge, the busy foraging of juncos, the darting to and fro of chickadees – it’s all a pleasure. Over the years, I’ve observed the birds here in my garden through my large kitchen windows; at the cottage on Lake Muskoka; in various public gardens; and in the nearby cemetery where I photograph trees and shrubs. In doing so, I’ve compiled a visual record of how gardens can attract birds without using bird feeders. Here are some ideas.

Conifers for Shelter and Food

Birds need places to nest and take shelter in winter, if they’re not migrating. My garden has two eastern hemlocks (Tsuga canadensis) at the back of the garden that I planted in the 1990s. They’re not beautiful, they developed multiple trunks and lost limbs and look a little ragged, but the birds do love them, like the male cardinal below.

Between my next-door neighbour’s property and mine is a large white cedar or arborvitae (Thuja occidentalis) hedge. This might be the very best garden habitat for birds. We keep it sheared so its growth is dense, helping to protect its inhabitants from the weather and predatory raptors. I’m always amazed that the birds know exactly where their home is inside this long leafy condominium, and fly at very fast speed right at it, disappearing into the lacy branches. (That purple birdhouse is more for looks – the birds haven’t taken up residence

In autumn, I see birds eating the arborvitae seeds, too, like the house sparrow below.

At our cottage in Muskoka just a few hours north of Toronto, chickadees, below, pine siskins and loads of other birds forage in the white pine trees (Pinus strobus).

Song sparrows with their wacky, beautiful melodies use the pine trees too….

…. as does the occasional ruffed grouse.

Fruit

There is nothing that attracts more birds to a garden than the fleshy fruit of trees and shrubs. Of course, that can be a negative if you’re trying to harvest your own grapes or cherries and need to net the fruit to deter birds as it ripens. But in my garden I have a few excellent woody plants whose fruit is dedicated to the birds. The first is crabapple – in my case, a weeping Malus ‘Red Jade’ over my pond (that sadly has likely lived its last summer, with increasingly intractable viral blight). Its small fruit and proximity to the water has always made it an extra-special treat, for robins….

…. and northern cardinals.

I have a pair of large, native serviceberry shrubs (Amelancher canadensis) that are a cloud of white blossoms in early spring followed by summer fruit that ripens from red to blue. It’s quite delicious, but I rarely get to pick a handful before the fruit has been eaten by robins….

…… or sparrows….

….. or cardinals, like this one tucking into a fruit on my deck railing.

My Washington hawthorn (Crataegus phaenopyrum) is a favourite tree. Though its late spring flowering is not exactly an olfactory treat, its mottled autumn colour and abundant clusters of red fruit (haws) make up for it. The fruit seems to need some cold weather to reduce the astringency, but I love watching the robins on it….

….. and the cedar waxwings, below. However, it’s usually my garden’s intrepid squirrels that finally strip the tree clean.

Staghorn sumac (Rhus typhina) is one of the most abundant native shrubs in the northeast, but it can be problematic in a garden. In short, it suckers far and wide. Though I grow a select cultivar called Tiger Eyes (‘Bailtiger’) featuring chartreuse foliage followed by lovely, apricot fall colour, it has the same tendency to pop up in surprising places quite removed from the main plant. That’s it below with another bird-dining favourite, white flowered, alternate-leaved dogwood (Cornus alternatifolia) behind it. It is my favourite shrub of all; I cannot recommend it highly enough where it is native, i.e. throughout much of eastern North America. Interestingly, my neighbour’s pale-pink beauty bush (Kolkwitzia amabilis) on the far right, an Asian native, has seeds that feed many birds in winter

Cornus alternifolia produces clusters of dark-blue fruit that are consumed quickly in early summer.

As for the Tiger Eyes sumac, lots of birds enjoy rooting for the seeds in the fuzzy red fruits, including blue jays….

…. and the cardinal family that lives in the hedge adjacent to it.

I made a little video of the male cardinal foraging on my sumac. (It’s not easy to hold my little, old Canon SX50 zoom camera steady from my kitchen window, which is 40-50 feet away from the sumac, so I’m always happy when I can capture a scene like this).

At the cottage on Lake Muskoka, the sumacs are all wild and their suckering doesn’t bother me, except when they try to creep into my meadows. They are not only a favourite browse for white-tailed deer but a valuable autumn-winter food for birds, including black-capped chickadees, below.

This autumn, I was surprised to see a pair of northern flickers on my old fence where the native Virginia creeper (Parthenocissus quinquefolia) grows in a tangle. Likely on their migration route, they took turns keeping watch while their mate nibbled on the fruit. Though it won’t win any awards, I was delighted with this photo showing the male’s yellow tail feathers.

There are other good native shrubs and trees to attract birds, including Northern spicebush (Lindera benzoin), below, nannyberry (Viburnum lentago), American mountain ash (Sorbus americana), elderberry (Sambucus pubens, S. canadensis), hackberry (Celtis occidentalis), black cherry (Prunus serotina), winterberry (Ilex verticillata) and various other dogwoods (Cornus racemosa, C. sericea).

And though it cannot be recommended, don’t be surprised to see birds eating mulberries (Morus alba) in older neighbourhoods where these European trees were planted long ago. It’s estimated that more than 60 bird species eat the fruit of mulberry trees– much to the chagrin of those who have to clean the purple stains off their outdoor furniture!

Flower Seeds and Weeds

Without a doubt, in my experience the best garden plant for providing nutritious seeds for birds is purple coneflower (Echinacea purpurea). I caught these goldfinches foraging in the Piet Oudolf-designed entry border at the Toronto Botanical Garden one autumn.

When I posted the video below on Facebook back in 2015, it was eventually shared almost 2 thousand times. My message? Don’t deadhead your echinaceas!

Here is a flock of goldfinches on my own pollinator garden echinaceas in October 2021.

Goldfinches also love coreopsis seeds, like those of C. lanceolata.

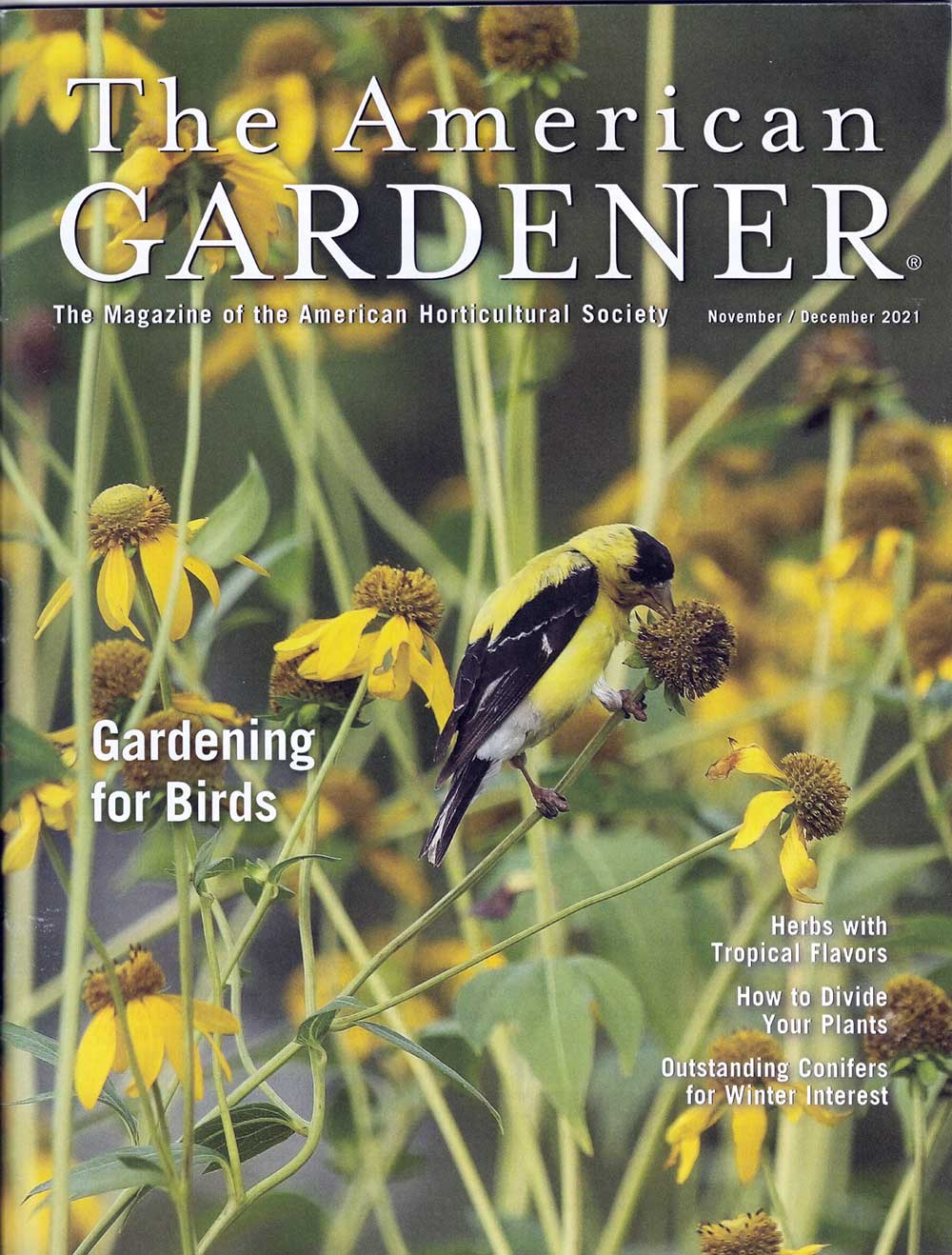

Rudbeckias also offer seed for birds. These goldfinches are on cutleaf coneflower (Rudbeckia laciniata).

In fact, my photo of a goldfinch on that native perennial was featured on a recent cover of The American Gardener magazine.

Canada or creeping thistle (Cirsium arvense), below, may be a pesky, invasive European weed, but there’s no doubt that goldfinches enjoy it – and help to spread it far and wide!

My meadows on Lake Muskoka attract many different birds to feed on flower and grass seeds in late summer and autumn. Wild beebalm (Monarda fistulosa), my most abundant perennial, attracts goldfinches, below, and chipping sparrows frequent the paths to eat fallen seeds, including those of my big prairie grasses: big bluestem, switch grass and Indian grass.

Ornamental grasses offer seeds for birds, provided they have a place to perch. The sparrow below stood on leadplant (Amorpha canescens) while eating seeds of switch grass (Panicum virgatum).

At the Montreal Botanical Garden, I enjoyed watching house sparrows foraging on the dark seeds of the ornamental millet Pennisetum glaucum ‘Purple Baron’.

Other good choices for seed include oaks for acorns and beech and hickory trees for nuts.

Needless to say, many trees also offer a variety of insects for birds, especially important for springtime feeding of nestlings. Oaks are recommended as a top genus by entomologist/ecologist Douglas Tallamy because of the huge number of insects that feed on them, up to three hundred.

Nectar for Hummingbirds

I’ve already written a blog on good plants for hummingbirds but I made this little video to add some nectar sweetness to this post. It features the ruby-throated hummingbird, which is the only native Canadian hummingbird east of the Rocky Mountains.

Water

Everything needs to drink, and birds are no exception. So while I don’t have a bird feeder, I do offer water in the form of my old pond. When I dug it in 1987 I had dreams of aquatic plants with gorgeous flowers, and I did grow waterlilies and floating plants for a while. But marauding raccoons were a constant irritant and eventually it was too difficult to lift out heavy pots to store for winter, since the pond is just a few feet deep. So today it’s a giant birdbath and water fountain (must fix the pump!) surrounded by too many weeds and prone to algae in summer, but it is so popular with the birds I cannot imagine my garden without it. Here it is with a pair of juvenile robins drinking and bathing.

Cardinals love the pond, too. This is a male and female pair in spring.

And here are cardinals bathing – such fun to watch (from a distance).

I have seen some sweet birdbaths in gardens, like the one below, but a pond fulfils that objective very nicely.

Dead trees and Snags

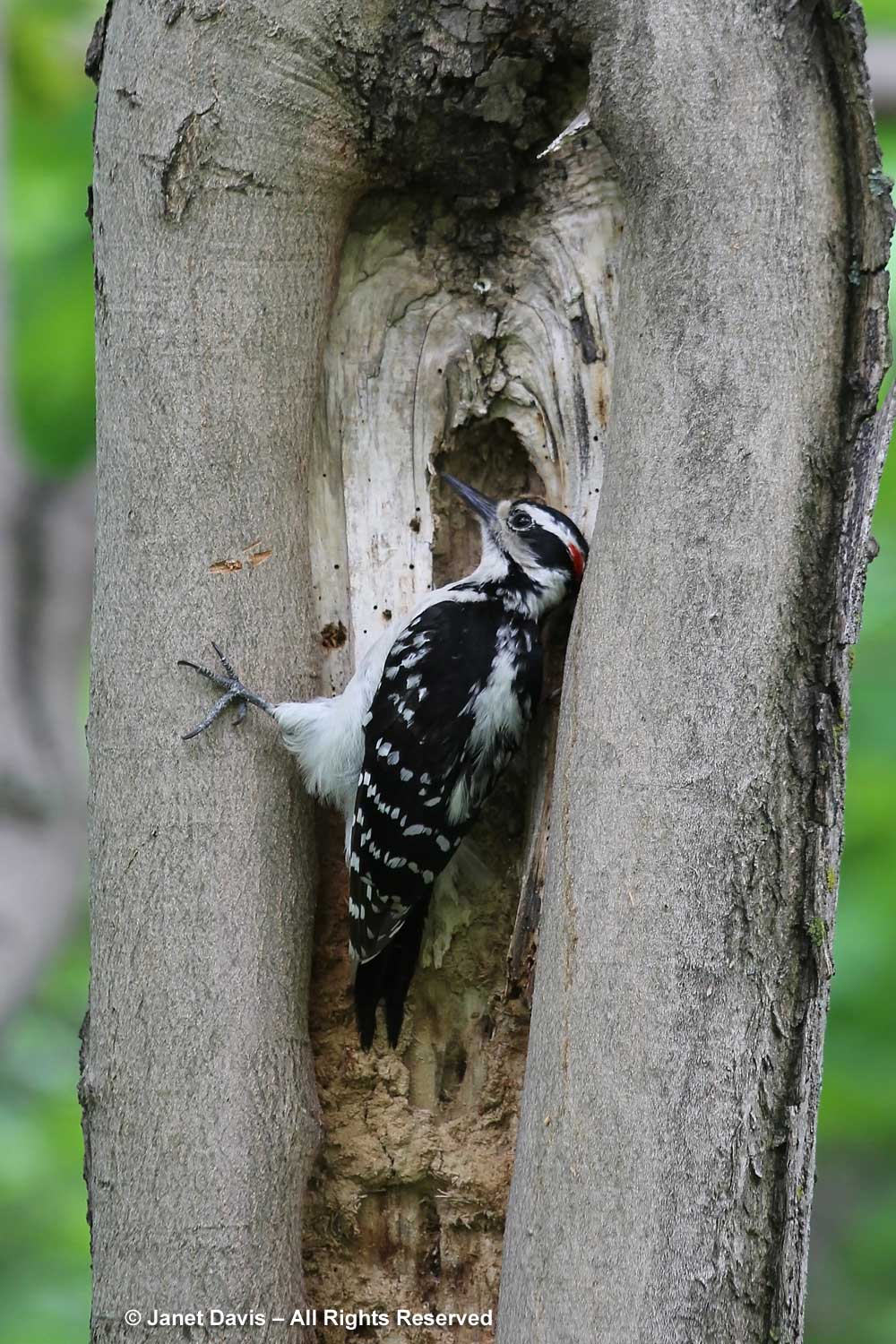

If you enjoy watching woodpeckers, you’ll know that they often frequent trees that are diseased or damaged, like the red maple below being visited by the hairy woodpecker.

Some are even dead – like my poor ash tree (Fraxinus pensylvanica), a victim of emerald ash borer a few years ago. But I left the base of the trunk in place, mainly because it would have cost a fortune (more) to cut it to ground level, grind the roots and repair the fence. It has become a stop on the foraging route of the woodpecker in the video, below.

******

Without foliage on the trees, winter is a good time to observe birds in the garden. On days when the local Cooper’s hawk, below, is searching for a tasty feathered meal, I am usually alerted by the persistent warning squawks of blue jays. It was a thrill to see this raptor perched in my crabapple tree.

This week, I watched chickadees, cardinals and dark-eyed juncos, below, eating the seeds of my next-door neighbour’s beauty bush (Kolkwitzia amabilis). A big, beautiful, old-fashioned Asian shrub, it also attracts lots of pollinators in June.

But spring will be here before we know it, and the robins will be searching for worms among my flowering bulbs….

… and in the lawn.

And Madame Cardinalis cardinalis will find a flowery forsythia in which to dry off and groom her feathers after a spring dip in my pond, while being serenaded by Monsieur Cardinalis cardinalis high up in my black walnut tree. I cannot wait!