This is a blog I’ve been meaning to write since 2018. What happened? Well, sometimes the sheer complexity of a topic with which I’m not very familiar triggers that “I’ll just get back to it later” response. And, of course, because I want to research everything to death I don’t find the time to get back to it. But I decided it was time to a) do the blog (with just a few photos….) and b) suffer the consequences of the many things I’ll likely get wrong. And a note of sincere thanks to the folks at the National Park Service who patiently answered my questions.

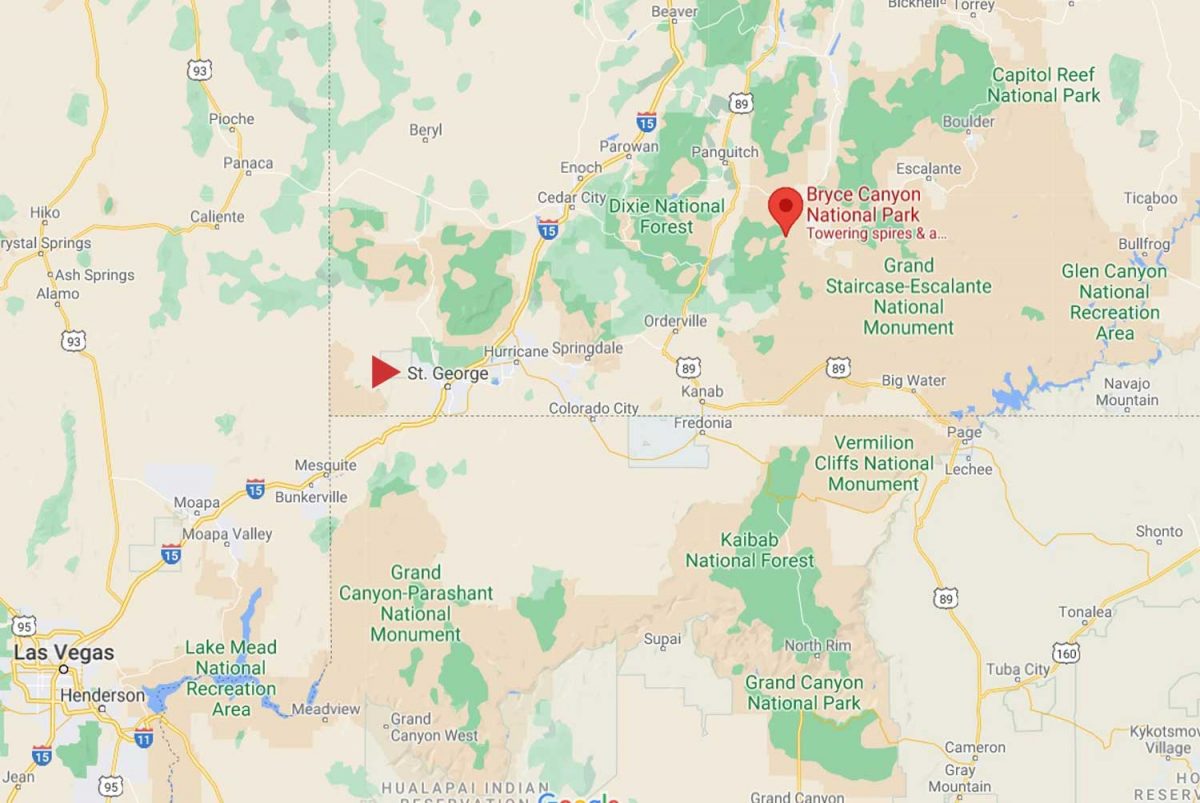

So…. back to late April 2018. We were visiting our dear friends Peter and Lynne who now live in St. George, Utah. It was our first time in the state and they wowed us on our first afternoon with a hike through their ‘local’ Snow Canyon State Park. Though Peter & Lynne usually ride their bikes there, we walked along the sagebrush-flanked road between peaks of white and orange Navajo sandstone deposited in the Early Jurassic, about 183 million years ago.

I was excited to find beavertail cactus (Opuntia basilaris) in flower along with sagebrush at Snow Canyon.

The next morning, I reluctantly took leave of Lynne’s lovely walled garden which is itself set in the desert….

….. and we climbed into their car and headed northeast on Highway 15 towards Bryce, a 2 hour-20 minute drive and more than 5,000 feet in elevation away. We made a brief stop at Kolob Canyons, the most westerly part of Zion Canyon, which wasn’t far from the highway to Bryce, but the main Zion show would occupy the second day of our road trip.

We passed through the Red Canyon in the Dixie National Forest. Legend has it that the notorious train and bank robber Butch Cassidy (not the nice Paul Newman movie version) travelled the trails here.

AT BRYCE CANYON NATIONAL PARK

An hour later we were standing near Sunrise Point at the northern end of the Rim Trail atop the southeastern edge of Paunsaugunt (PAWN-sa-gunt) Plateau gazing out at the massive natural amphitheatre that forms Bryce Canyon National Park.

There are no railings along most of the Rim Trail. Lynne got as close to the edge as she could to try to capture some of the magic. Bryce is what it is because of the forces of weather-induced erosion over millions of years, and the eastern side of the Paunsaugunt Plateau is eroding at a rate of 2-4 feet per century along with it. Thus, in 3 million years, it’s estimated that Bryce Canyon will be gone.

As a garden writer, I was delighted to find lots of plants at the rim, like this wonderful ponderosa pine (Pinus ponderosa) framing a big view.

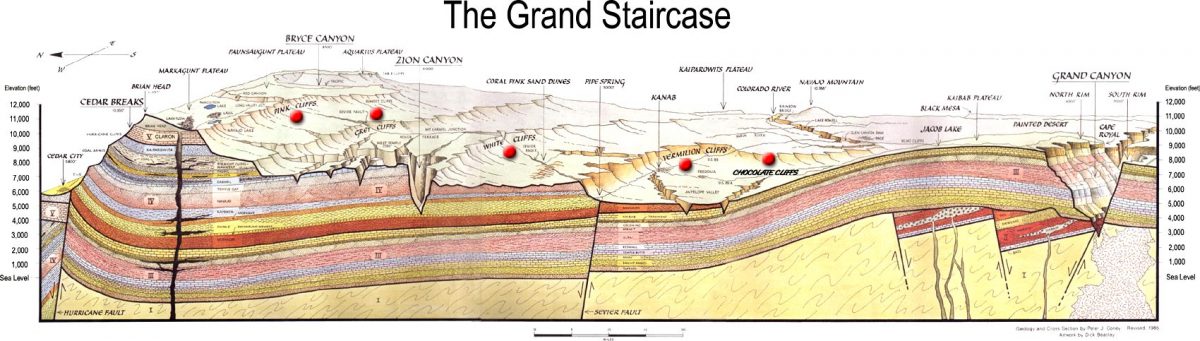

“Spectacular” is simply too underwhelming a word to describe the various vistas in this remarkable 36,000-acre (56 square mile) park with its thousands of hoodoos, spires, caves, alcoves and bridges arrayed over 14 named amphitheatres (i.e. canyons). This was my favourite view, spanning Bryce Canyon with flat-topped Boat Mesa on the left, slanting Sinking Ship in the centre, stretching across the valley to the Table Cliff Plateau in the distance. Extending south from here is the Grand Staircase or Escalante (so named by 19th century geologist Charles Dutton) describing descending sedimentary formations celebrated in various parks and monuments including Zion and culminating with Grand Canyon National Park whose rocks range from 280 million to 1.8 billion years old. The elevation at Bryce ranges from 8,000-9,000 feet (2,400-2,700 m). Bryce, Zion and the rest of the parks of the Grand Staircase are all part of the High Plateaus section of the Colorado Plateau which uplifted 20 million years ago.

According to the US Geological Survey, “The rocks of Bryce Canyon tell a story, revealing the past environments of the area. At various times in the past, this region was a floodplain, part of a sea, and a desert. The Colorado Plateau, beginning about 50 million years ago, was a mostly flat part of a lake and floodplain system. This area was surrounded by higher elevations, carrying sediment downwards where it was deposited. The sediments were cemented over time to form various sedimentary rocks, including sandstones, dolostones, limestones, and mudstones. At this point, the region we now call the Colorado Plateau was near sea level. The next major event was a collision of the North American Plate and the Farallon Plate, causing the Farallon plate to subduct and generate heat that drove the Colorado Plateau upward to its current elevation. This helps explain how we can have marine sediments at both a high elevation and in the middle of a continent. This uplift exposed the rocks to the elements, allowing weathering to create new formations and making the layering visible.”

Boat Mesa rises to 8073 feet and separates Fairyland Canyon in the north end of the park with its mainly undeveloped formations from the main amphitheatre with its masses of chiselled hoodoos to the south.

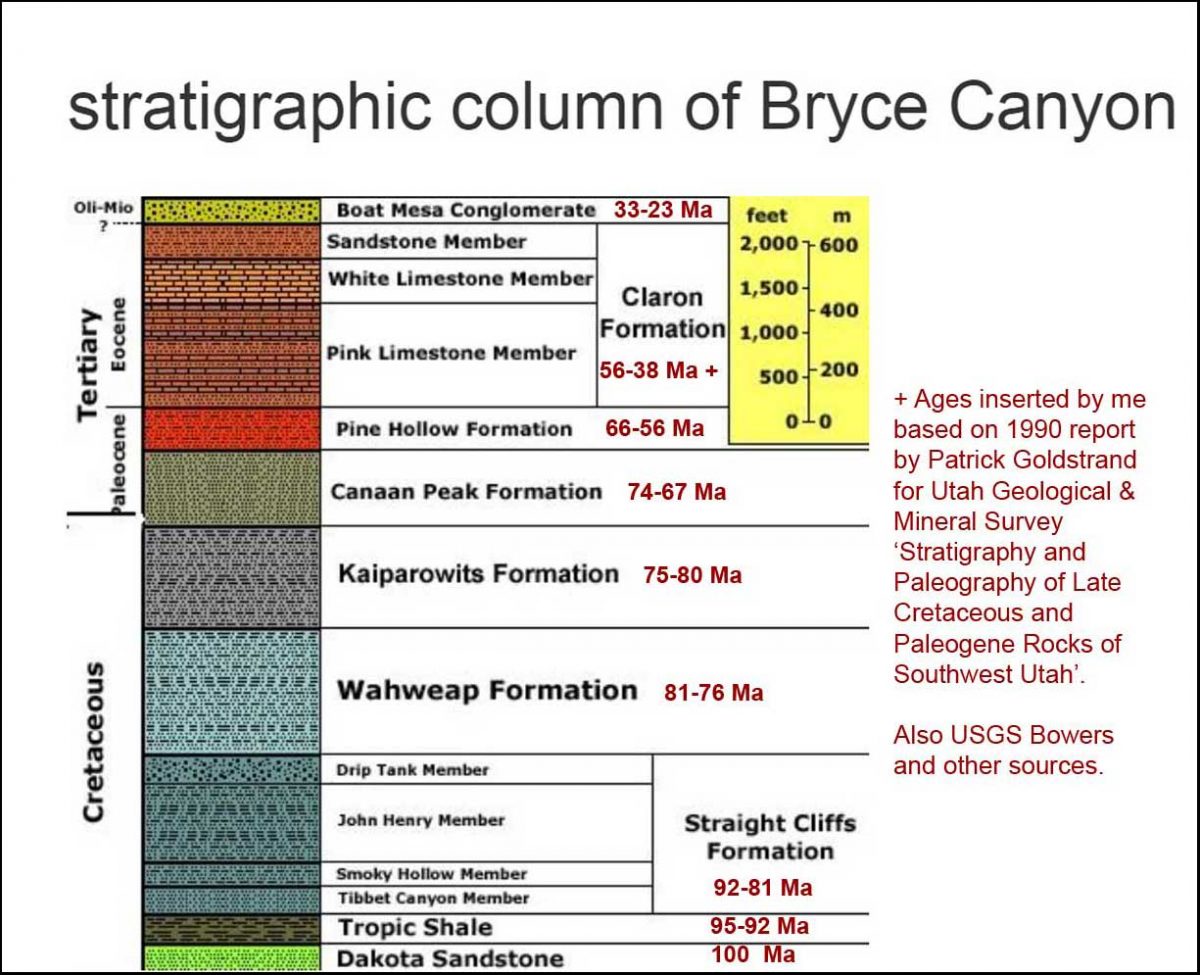

Topping Boat Mesa is a flat, erosion-resistant, grayish rock layer not found elsewhere in the park which the National Park Service (NPS) calls the Boat Mesa Conglomerate. Estimated to be 20-30 million years old, it is higher – and therefore younger – than the rest of the formations or rock members in the park, including the c.50 million-year old Claron Formation that dominates the amphitheatres in most of Bryce. (I’ll get into the geology more later).

Sinking Ship is an apt description of the sloped mesa below. According to the NPS, “The uptilt of Sinking Ship results from its position along the basin and range-associated Paunsaugunt fault. These rocks are a reminder of the tectonic activity that began 15 million years ago, raising the Paunsaugunt Plateau to its present elevation and dragging sections of rock along the faults, resulting in the tilt we see today. Earthquakes in recent years remind us that Earth is constantly adjusting and that activity along those faults continues, although in relatively minor magnitudes.” Beyond is the Table Cliff Plateau, which ends at Powell Point. In the greyish valley between Bryce and the Table Cliff Plateau is the little town of Tropic, where we would have dinner that evening. The town is the ‘type locality’for the fossil-rich (dinosaurs, sharks, turtles, ammonites) Tropical Shale formation, which was named in 1931.

According to the NPS, “The Table Cliff plateau stands at 10,000 feet (3048 m) and is composed of the same Claron formation (or “Pink Cliffs”) as Bryce Canyon’s hoodoos. This difference in elevation is due to the presence of the Paunsaugunt fault–a major normal fault that runs northeast to southwest along the park’s eastern boundary. Uplift of the Colorado Plateau over the last 20 million years is responsible for the nearly 2,000 feet (607 m) of elevation difference expressed by this fault. Below these Pink Cliffs, observe the shale-rich badlands of the Grey Cliffs slowly transform to the sometimes iron-rich sandstones of the upper White Cliffs.”

Limber pine (Pinus flexilis) is part of the Bryce plant community on the rim and at higher elevations in the amphiteatres.

Grizzled old Utah junipers (Juniperus osteosperma) clung to the plateau rim.

Behind the Rim Trail is the Horse Trail. As far back as 1931, the NPS honoured traditional exploration on horseback in the canyon; today there’s a 2.9 mile horse trail loop. Visitors can rent horses for individual riding or for guided horseback tours.

Hikers were coming back up from the Queen’s Garden Trail, one of many trails throughout Bryce. The Queen’s Garden Trail is 0.9 miles and is considered easy, while many are long and taxing.

The rich soil colours here and throughout the sedimentary formations of southwest Colorado are fascinating – especially if you live on Canada’s gray, granitic Precambrian Shield like me. In a word, it’s all about iron, one of the most abundant elements in the earth’s crust, and how it oxidizes to form other minerals. Hematite (Fe2O3) is responsible for the pink colours of the Claron Formation here. Because of its reddish colour, the Greeks called it αἷμα (haima), the word for blood, the root word for hemoglobin.

You can see visitors hiking the Queen’s Garden trail in the left of the image below.

Here’s a young limber pine (Pinus flexilis). Older trees often cling to the rim via prop roots as the soil erodes away beneath them. True to the words of iconic writer Donald Culross Peattie as displayed on the signage here: “Limber pines have a way of growing in dramatic places, taking picturesque attitudes, and getting themselves photographed, written about, and cared for….”

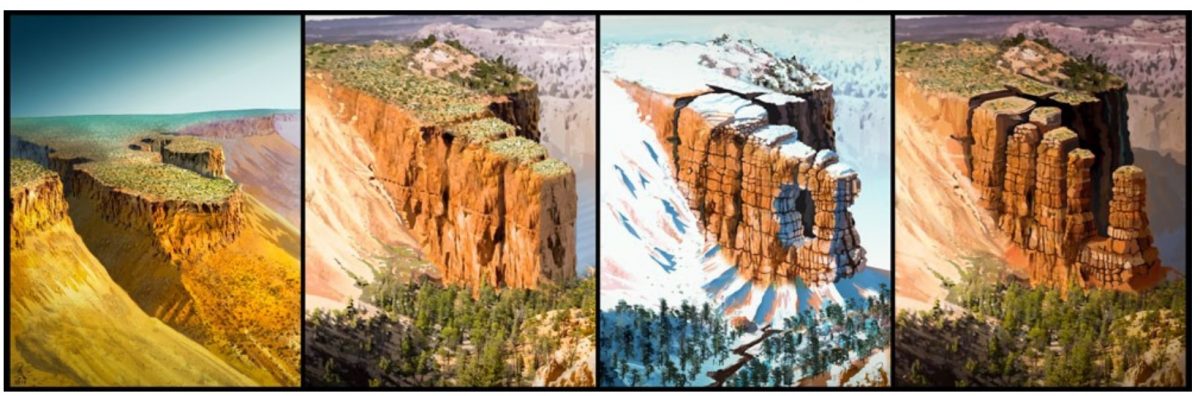

The story of Bryce Canyon’s iconic hoodoos, below, began 50 million years ago at sea level, some 9,000 feet below today’s elevation. At that time there was an ancient lake (Lake Claron) and floodplain here, its basin comprised of soils washed from nearby highlands. There were layered limestones, dolostone, mudstone, sildstone and sandstones. Some 30 million years later, plate tectonics in the form of the subduction of the Farallon oceanic plate under the North American plate raised the Colorado Plateau, lifting with it colourful oxidized rocks and soils of southwest Colorado. Over millions of years, ice and rain and the 200 days annually where Bryce receives both above- and below-freezing temperatures have united to become forceful agents to weathering and erosion. When rain and snowmelt seep into the rocks and become trapped there as night falls and the temperature drops, the water freezes, expanding by 9%. This process, called “ice wedging” breaks the rock apart, first into walls or “fins”, then windows, then into the columnar hoodoos topped at first by harder capstone (the white dolostone or dolomitic limestone, below), then further eroded – the hoodoos that give the Bryce amphiteatres their dramatic appearance.

This graphic shows the weathering process from intact plateau to wall-like “fin” to formation of window to the columnar hoodoos.

In the photo below, you can see windows forming in the pale limestone formation at the upper left.

The trees growing in the canyon seem to have narrow profiles like the hoodoos themselves. Limber firs also grow tall and narrow there.

A closer look at a narrow tree thought to be an Engelmann spruce (Picea engelmannii), which is a high-altitude mountain tree native to a large part of the west.

Benches are placed along the rim trail, like this one under an old juniper.

The appropriately-named Mormon tea (Ephedra viridis) recalls Ebenezer Bryce (1830-1914), the Scots-born pioneer who converted to the Church of Latter Day Saints as a teen, causing him to be disowned by his father. He became a ship’s carpenter, emigrated to Utah, married and built the Pine Valley Chapel for the Church of Latter Day Saints in 1868. When the park was made a national monument in 1923, it was named for Ebenezer Bryce.

I also saw greenleaf Manzanita (Arctostaphylos patula) ……

….. and noted the little holes made by bees intent on nectar theft, rather than pollinating the hard-to-access corollas of the flowers.

The fruit of the Manzanita is edible and used by the Paiute Indians who have called the Paunsaugunt Plateau home for hundreds of years. I liked this video from the NPS describing how the native people lived with the resources from the area.

You can see hikers on the switchback trail below. Check out the little ‘door’ in the wall between the two trees.

Near Sunset Point, a raven wheeled overhead while visitors descended into the amphitheatre.

It was fun to watch visitors hiking through the hoodoos. It gave a sense of the impressive scale, which is hard to appreciate from the rim.

Some took turns posing for the perfect shot.

I loved this view of Boat Mesa in the distance…..

…. and this one of Sinking Ship from a new angle. . If you look closely, you’ll see tiny horses on the trail at the bottom right.

This formation is called Bristlecone Point, celebrating the wonderful, old Pinus longaeva trees in the park (which, sadly, I missed seeing.) The oldest Great Basin bristlecone pine at Bryce is 1,500 years, still young for that species which keeps its needles for 40 years (compared to white pine’s 2-year needle retention). The exact location of the oldest-known bristlecone, 4,852-year-old Methuselah, is kept secret but is somewhere in the Inyo National Forest, California. It is also the oldest-known non-clonal tree in the world.

We backtracked on the rim trail to make a short stop at Bryce Canyon Lodge. Built in 1924-5, it was designed by Gilbert Stanley Underwood who also designed the rustic National Park Service lodges at Zion, Grand Canyon and Yosemite. But Bryce is the only remaining completely original structure.

Inspiration Point is beyond Sunset Point….

….. and the view here is indeed inspirational.

Looking beyond the raven sitting atop the white cliffs part of the Claron Formation, I could see visitors at the Bryce Point lookout a fair distance away. It was my next stop on the rim trail.

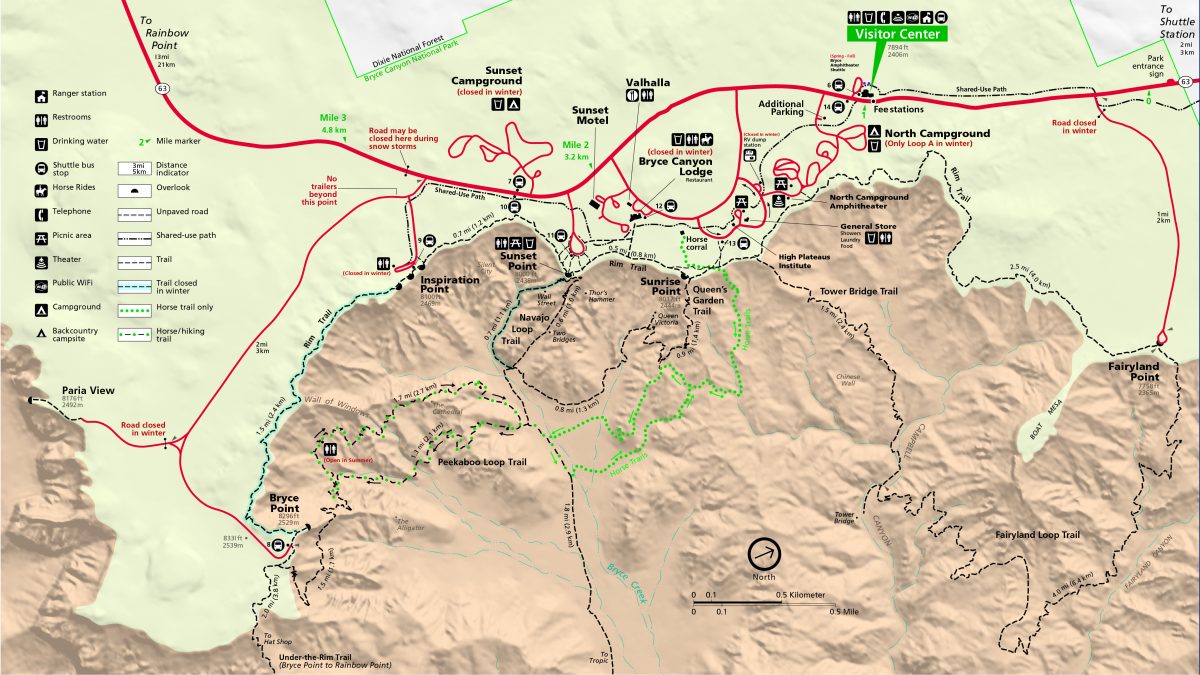

This map is helpful to sort out the various features on the trail.

Notice the elevation at Bryce Point, 200 feet above Inspiration Point. Though it’s a little walk from Inspiration, you don’t get the feeling that you’re climbing the equivalent of a 20-storey building.

Check out the visitors standing on the Bryce Point lookout.

As I walked on the path to the lookout, I made this photo, which shows graphically how the rim is slowly forming a vertical joint or slot here. But what a spectacular view of the Bryce Amphitheatre!

Below you see Bryce Creek running through Bryce Amphitheatre. Outside the park’s boundary, it connects to the Paria River.

Beyond the Bryce Amphitheatre rim, you can see the Sevier Plateau with the Black Mountains in the distance.

The upper rim shows sedimentary layers of the Claron Formation made over millions of years, each expressing different colours depending on the nature of the sediment in the basin of Lake Claron.

You can see the west side of the Peekaboo Loop trail behind the young hoodoos, below.

This is known as the ‘wall of windows’. They look like caves, but they’re on their way to becoming hoodoos.

Pine trees take root everywhere at Bryce.

“The Alligator” is an interesting formation, so-called because of its sprawling shape. It’s actually white dolomitic limestone, aka dolostone, a carbonate-rich rock that forms the erosion-resistant caprock shielding the softer pink formation below. It sits at 7,600 feet, seven hundred feet lower than Bryce Point.

Curl-leaf mountain mahogany (Cercocarpus ledifolius) is an attractive, small tree and fairly common at this elevation. Paiute Indians steeped the dried bark to make a medicinal decoction for respiratory disorders.

For our final stop at Bryce, we drove to Rainbow Point at the most southerly end of the park.

There was more dense forest in the amphitheatre here.

Douglas firs (Pseudotsuga menziesii) are common at this eleveation at Bryce.

The viewpoint here looked through a gap in the white limestone member downwards toward the pink limestone of the Claron Formation. I mentioned about a thousand photos ago that I’d get back to geology, so….

…. here is the stratigraphy of Bryce with approximate ages.

And here is an illustration of the Grand Staircase, showing Bryce at the upper left and the Grand Canyon at lower right. That cleft partway along the bottom – Zion Canyon – would be our next stop on the road trip.

After a long day, it was time to find our lodging for the night and then some dinner in nearby Tropic. But Bryce Canyon National Park was one of my favourite days of touring, all these otherworldly sculptures of rock – each sculpted a little differently from its neighbour by the elements throughout millions of years.

It was a window – or in this case, an arch – into the storied geological past of one of the most spectacular places in North America.

I made a musical video of my visit to Bryce Canyon National Park.

As a final bit of trivia, there’s a geological feature near Bryce called the Ruby’s Inn thrust fault that runs east-west between the Sevier and Paunsaugunt Faults (which run north-south), causing older Cretaceous age rocks to be deposited atop younger Eocene Rock. Fortunately, it’s seismically inactive so all was quiet as we tucked into our beds at the eponymous Ruby’s Inn, established here in 1923. And the next morning, May 1st, we awoke to another one of those 200+ days annually where Bryce receives both above- and below-freezing temperatures, wedging a little more ice into that great amphitheatre of rock.

********

If you enjoy reading about geology (from an amateur), you might like my blogs on

* Oregon’s Thomas Condon Paleontology Center

* My Jaded Past, My Rocky Present (a personal memoir)

Beautiful photos!

Thanks Jen! Hard to take a bad shot at Bryce!

Wonderful photos and descriptions, Janet. I love seeing the great parks of the West, and haven’t made it to this one yet, but it’s on my list! You captured the beauty of it well.

Thank you Pam. So many amazing parks and monuments on the Colorado Plateau. Next up on my blog will be Zion. But I do want to get to Yosemite some day so I envy your trip there!

Oh my, what a beautiful place. I haven’t been and hope to go someday. Loved the music video!

Gail… the parks there are magical!

Thank you for such a wonderful tour and history,

Glad you enjoyed it Carol!