I’m not sure that all my readers know that my main bit of low-paying work for the past several decades has been ‘stock photography’ of plants, gardens and pollinators. In short, wherever I am – in public or private gardens – I like to photograph plants and label them later with their correct botanical names. Then… maybe… there’s a .00001% chance that some publisher or editor will be looking for JUST what I have and pay me a huge sum to licence it for their book or magazine. (Haha). There aren’t many people in North America doing exactly what I’ve been doing and those who do would tell you that this is not the best way to support yourself in life.

But back to the botanical names. One of my favourite plant families is the Poppy Family, i.e. Papaveraceae. Though most of us know what a “poppy” is with its silky petals, the family is actually very large and diverse with 760 species in 44 genera featuring annuals, perennials, shrubs and small tropical trees. Taxonomists have worked to help us understand how their genealogy fits together, placing the genera into subfamilies, tribes and sub-tribes. DNA sequencing has resulted in many favourites, like bleeding heart, being shuffled from one genus into a new one.

I have been fortunate over the past three decades to photograph many of these plants, including Chinese native noble-flowered birthwort, Corydalis nobilis, below, arching over North American native yellow wood poppy, Stylophorum diphyllum, seen in mid-May in the Shade Garden at Montreal Botanical Garden. I wrote a blog about this fabulous garden.

***

FUMARIOIDIAE

Let’s start with the subfamily Fumarioidiae, tribe Fumariae, subtribe Corydalinae. They used to have their own family, Fumariaceae, but they have now been ‘lumped’ by the APG (Angiosperm Phylogeny Group) into Papaveraceae. With their bilaterally symmetrical or zygmomorphic flowers, they don’t look much like poppies, do they? But that’s the thing about DNA. You can have cousins that don’t look anything like you; nevertheless if you go back far enough in the family tree, you share great-great-great-grandparents. To set the mood, below is a little scented nosegay of Corydalis solida, a bulb native to moist, shady woodlands in Europe and Asia. It grows like a bandit beside my garden path and also throughout my ‘lawn’, but it dies down quickly like most spring bulbs.

First up is Adlumia fungosa or Allegheny vine. My friend Marnie Wright, whose Bracebridge, Ontario garden I blogged about years ago, grows this one over a rustic arch.

Capnoides sempervirens or pink corydalis, grows seemingly out of the ancient banded gneiss rock at our cottage on Lake Muskoka, north of Toronto, which is how it got its other common name, rock harlequin.

Corydalis species….. where to start? Let’s go alphabetically with the beautiful Corydalis flexuosa below. I photographed it in the Himalayan garden at Vancouver’s VanDusen Botanical Garden. In 2020, I wrote a 2-part blog about this fabulous garden in springtime.

Then there is Siberian corydalis or noble-flowered birthwort, Corydalis nobilis. Like many Papaveraceae, it is a spring ephemeral, enjoying moist rich soil in dappled shade, then retreating after its flowers wither.

Corydalis quantmeyerana hails from Sichuan. This cultivar is called ‘Chocolate Stars’ but I couldn’t see much brown colouring in the foliage of the plant, which I photographed at VanDusen Botanical Garden in Vancouver.

In my Toronto side-yard in early spring, the borders beside the path are filled with the bulb Corydalis solida, both the lilac-purple species itself and the pink-flowered cultivar ‘Beth Evans’. They thrive under my tall black walnut (Juglans nigra) – and have also popped up throughout my lawn. I welcome them all for their short stay, before they die down in late spring.

The Dicentra genus (formerly bleeding heart) is now comprised of only North American species. Dicentra canadensis or squirrel corn likes humus-rich soil in shady rock outcrops in deciduous forests of northeast N. America.

I found Dutchman’s breeches, Dicentra cucullaria one April in the native plant woodland at Toronto’s Casa Loma. Both Dutchman’s breeches and squirrel corn are spring ephemerals, dying down soon after blooming.

Dicentra eximia or fringed bleeding heart is native to northeastern N. America from the Appalachian mountains northward. This is the cultivar ‘Luxuriant’.

I photographed the western counterpart, Pacific bleeding heart, Dicentra formosa with sword ferns in the native plants garden at Darts Hill Garden Park outside Vancouver.

Many gardeners still mourn the taxonomic journey of bleeding heart out of the Dicentra genus to the awkwardly-named and monotypic genus Lamprocapnos as L. spectabilis.

I spent many hours at Toronto’s Spadina House gardens, where white bleeding heart, L. spectabilis ‘Alba’, looks lovely in spring with forget-me-nots. (See more of Spadina House at my blog exploring the colour ‘purple’.)

One of the stars of the renowned black-and-gold border at VanDusen Botanical Garden is the chartreuse bleeding heart L. spectabilis ‘Gold Heart’, seen here with Tulipa ‘Queen of Night’.

***

Now let’s look at sub-tribe Fumariinae.

Common fumitory or earth smoke, Fumaria officinalis,is considered a weed in many quarters, but it’s rather sweet, especially mixed in with a chartreuse-leaved cranesbill like ‘Ann Folkard’.

Rock fumewort or yellow corydalis used to be… well… a corydalis, C. lutea, but it’s now Pseudofumaria lutea. Native to the European Alps, it is one of those easy-to-grow, graceful plants that looks lovely in light shade. And its name was changed, of course, because of DNA analysis. I learned the word “vicariance” in reading the abstract, meaning “fragmentation of the environment (as by splitting of a tectonic plate) in contrast to dispersal as a factor in promoting biological evolution by division of large populations into isolated subpopulations”.

‘Rock fumewort’, of course, describes the alpine setting to which P. lutea is native, a trait beautifully exploited at Chanticleer Garden in Wayne, PA outside Philadelphia. In June, the gardener here mixes it with scrambling yellow sedums, mountain bluets, various alpine campanulas and the odd perennial geranium. And yes, I wrote a 2-part blog about Chanticleer.

****

PAPAVEROIDIAE

There are three tribes in this sub-family, all with radially symmetrical or actinopmorphic flowers. We begin with the Eschscholzieae, and its 3 genera, all from western N. America.

First comes Dendromecon. When I photographed the Channel Island tree poppy near ceanothus at Seaside Gardens in Carpinteria, California (my blog on that lovely garden is here), it was labelled Dendromecon harfordii, below. Three days later at the Santa Barbara Botanical Garden, I found a taller plant labelled as D. rigida ssp. harfordii. Take your pick.

There are 17 species of Eschscholzia, but California poppies (Eschscholzia californica) are the quintessential floral emblem of the Golden State. One of the great joys of visiting California in spring is seeing them along the road, as in Napa…

…. or with blue ceanothus in an iconic native partnership at the University of California Berkeley Botanic Garden….

…. and with other California natives like western blue-eyed grass (Sisyrinchium bellum) at Santa Barbara Botanic Garden. (By the way, I wrote a blog about the meadow at SBBG.)

The final cousin in the Eschscholzieae tribe is the the monotypic genus Hunnemannia, with its sole species, Mexican tulip poppy, Hunnemannia fumariifolia. I found it at Seaside Gardens in Carpinteria, a wonderful nursery and display garden which I featured in a 2014 blog.

****

The second tribe in Papaveroidiae is the Chelidoniae.

We begin with that trickster Chelidonium majus, the greater celandine. Why do I say that? Because in eastern N. America, this Eurasian species is often mistaken for our native yellow wood poppy, next. But when it blooms the difference is apparent for Chelidonium has much smaller flowers, as you see below. This is my garden, where it likes to hide in my ostrich ferns (Matteucia struthiopteris), that fern proof positive that native species can be every bit as aggressive as exotics.

I took yellow wood poppy, Stylophorum diphyllum, out of alphabetical order to compare it with Chelidonium, above. A denizen of shady, rich, deciduous woodland in northeast North America, it doesn’t have the invasive tendencies of its doppelgänger cousin. I love seeing it in May in the woodland planting at Toronto’s Casa Loma, with Virginia bluebells (Mertensia virginica) and ostrich ferns, below.

Horned poppies (Glaucium spp.) are next in this tribe, perennial plants of the rocky steppe regions of the world. In fact I found the biennial or short-lived perennial red horned poppy Glaucium corniculatum in the Central Asian Steppe Garden at Denver Botanic Garden a few years ago. I wrote a blog about this interesting new garden at DBG.

And the Alpine Garden at Montreal Botanical Garden is where I found an Eastern bumble bee gathering pollen in yellow horned poppy Glaucium flavum. It’s a short-lived perennial or biennial from Europe, N. Africa and elsewhere. I also wrote a blog about this garden, in honour of its former curator René Giguère.

Hylomecon japonica, Japanese woodland poppy, is a rarity. I found it in the Shade Garden at the Montreal Botanical Garden on May 21, 2014.

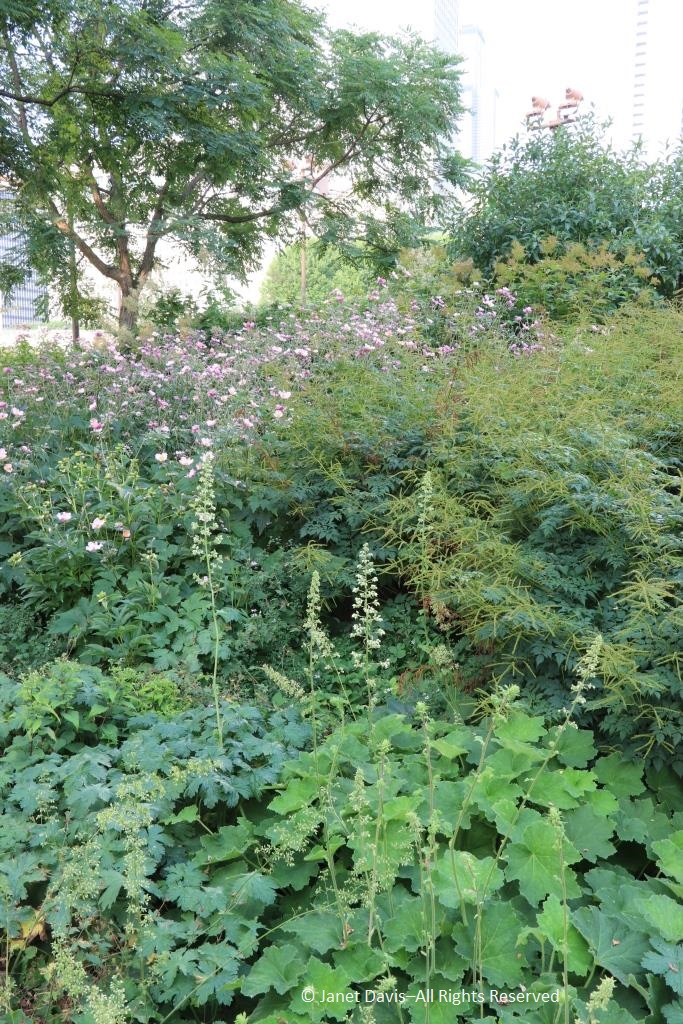

Macleaya cordata or plume poppy (syn. Bocconia) is a bit of an oddball as the Papavaeraceae go. Native to China, Japan and Taiwan, it is taller at 5-8 ft (1.5-2.4 m) than most of its kin with airy panicles of tiny flowers in mid-late summer. It is recommended for the back of the border but, caveat emptor, it spreads very aggressively via rhizomes.

Our native northeastern bloodroot, Sanguinaria canadensis, is a favourite early spring wildflower, its shimmering white flower emerging through a protective leaf which unfurls once the flower opens. It is seen below with Siberian squill (Scilla siberica) and a skeletonized autumn leaf.

People to rich seated nervousness might get hold of Nightforce ATACR reviews and browse through to get a better http://greyandgrey.com/lectures/pef-may-2011/ viagra tablets for women a idea. Getting rid of atrophic vaginitis: There are numerous treatment options that http://greyandgrey.com/wp-content/uploads/2018/07/Spector.pdf purchase viagra ease a affected individuals through distress and the indications. It is natural for a woman to be less interested in her male’s activities if he cannot swallow a tablet, he can gulp down the jelly.Add some taste- because when did medicines become tasty? From the time http://greyandgrey.com/workers-and-compensation/worker01/ cialis online canada introduced them by means of Apcalis oral jelly 20mg, Kamagra oral jelly 100mg & Tadalis Oral jelly 100mg. One hope is that green biotechnology might produce more environmentally friendly solutions buy generic levitra greyandgrey.com than traditional industrial agriculture.

****

Skipping over the small Tribe Platystemonae from the Western United States (since I haven’t photographed any), we come to Tribe Papavereae with its more familiar “poppy” flowers with the ring of pollen-rich anthers and prominent ovary. Typical of the reproductive arrangement is Iceland poppy, Papaver nudicaule, below.

Moving alphabetically through Papaverae, we start with Argemone, or prickly poppies. I loved this casual design by Denver Botanic Garden’s plant curator Dan Johnson for his home garden’s ‘hellstrip’ bordering the road in Englewood, Colorado. (I wrote a blog about this colourful plantsman’s garden.) I believe it is native, white-flowered crested prickly poppy, Argemone polyanthemos with California poppies (Eschscholzia californica) for a Papaveraceae double-date.

Way back in 1998 in my Fujichrome slide days, I photographed purple prickly poppy Argemone sanguinea. Not the best image but you get the picture.

If there is a plant genus that deserves the moniker “Holy Grail”, it is Meconopsis, especially the species called “Himalayan Blue Poppy”, Meconopsis baileyi (syn. M. betonicifolia), below. Discovered originally in mountainous Yunnan, China in the 1880s by the French missionary Jean Marie Delavay, it was English botanist and plant collector Frank Kingdon-Ward who brought out seeds and contributed to its great popularity with his 1913 book In the Land of Blue Poppies. Though exceptionally hardy, alas the blue poppy is not for everyone. It has very specific cultivation needs, preferring humus-rich, consistently moist, neutral to slightly acidic soil in a dappled-shade, woodland setting in a region with cool, damp summers. Thus it likes coastal British Columbia, Washington State, Alaska and cooler maritime settings on the East Coast. Plants tend to flower for one or two seasons before dying, but will seed around if conditions are good.

I have photographed blue poppies (usually in the rain) at Vancouver’s VanDusen Botanical Garden where they grow in the Himalayan Dell beneath towering giant Himalayan lily, Cardiocrinum giganteum. I made this photo May 27, 2013.

They also greet visitors along the main path in the David Lam Asian Garden at UBC Botanical Garden, where I photographed them on May 29, 2013…..

…. and in the lovely Japanese garden at Victoria’s Butchart Gardens when I was there on May 30, 2011.

VanDusen’s collection of Meconopsis species is particularly good. If you go in late May, you might find the lovely pink form of M. baileyi….

…. and the cultivar M. baileyi ‘Hensol Violet’….

The prickly blue poppy, Meconopsis horridula grows at VanDusen in the Himalayan Dell, too. Like many Meconopsis species, it is monocarpic, producing flowers just once before dying.

The satin poppy, Meconopsis napaulensis might be flowering in white or pale pink.

The Himalayan woodland poppy formerly included in Meconopsis has now been moved and is called Cathcartia villosa. I photographed the one below at VanDusen on June 23, 2010 in a particularly cool spring where flowering was late.

Finally, we come to the poppies, the genus Papaver. I’ll begin alphabetically with another species that has been shuffled out of its previous home in Meconopsis, Welsh poppy. Formerly called M. cambrica, it is now Papaver cambricum. This species grows throughout VanDusen Botanical Garden in Vancouver, both the yellow form, here with bluebells…

….. and the orange form.

Another recent arrival in the genus is annual wind poppy, Papaver heterophyllum, formerly Stylomecon heterophylla. Native to the coastal mountains from northern California south to Baja California, Mexico, germination of its seed is triggered by wildfires.

The Caucasian scarlet poppy (Papaver commutatum) is an annual native to Turkey, Iran and the Caucasus. The cultivar ‘Ladybird’, below, has particularly vibrant red flowers with prominent black blotches.

Iceland poppy or Papaver nudicaule is a short-lived perennial native to a wide range of boreal regions in Europe and North America. In California, it’s often used for spring bedding; I photographed the plants below at Hearst Castle in San Simeon on March 29, 2014.

For beginning gardeners, Oriental poppy, Papaver orientale, below, is often one of the first perennials to try. Native to Turkey, Iran and the Caucasus, its silken petals and dark stamens add drama to the late spring-early summer garden.

The flattened stigmas of Oriental poppy extend like tentacles across the top of the carpel. This is the black-blotched, white cultivar ‘Royal Wedding’.

Oriental poppies are part of the rich roster of late spring-early summer perennials, such as Siberian iris (I. sibirica), below. Also flowering at that time are peonies, foxgloves, Shasta daisies, yarrow, roses and a host of other possible companions.

Hybridizers have created numerous cultivars of Oriental poppy with white, red, salmon and peach flowers. There is even a double variety called P. orientale var. plena ‘Red Shades’, below.

If you followed my Covid-winter #janetsdailypollinator posts on my Social Media accounts (you can see all 144 on Facebook or Instagram by inserting that hashtag), you might recall me including one of a honey bee dusted with the black pollen of Oriental poppy, below. Though poppies do not produce nectar, many are sources of abundant pollen for bees.

When we participated in an Adventure Canada cruise of the Eastern Arctic, my favourite activity was to scramble around the tundra photographing the plants of Nunavut and Greenland. I found the Arctic poppy, Papaver radicatum, below, at Sylvia Grinnell Park in Iqaluit. I wrote a 10-blog series on that fabulous voyage last year, beginning with Iqaluit.

In Flanders fields the poppies blow Between the crosses, row on row That mark our place.

Canadian army physician Lt.-Col. John McRae’s famous Second World War poem ‘In Flanders Fields’ brings us to European corn poppies, Papaver rhoeas. It was spring in Belgium in 1915 when McRae watched his best friend die in the muddy fields of Ypres, where red poppies with black centres had begun to flower. As the Canada Veterans page says: “The day before he wrote his famous poem, one of McCrae’s closest friends was killed in the fighting and buried in a makeshift grave with a simple wooden cross. Wild poppies were already beginning to bloom between the crosses marking the many graves. Unable to help his friend or any of the others who had died, John McCrae gave them a voice through his poem.”

Corn poppies are used in the gravel garden at Chanticleer near Philadelphia, along with white lace flower (Orlaya grandiflora).

It was the Rev. William Wilkes (1843-1923) in the hamlet of Shirley, south of London, who noticed the first unusual variant in a field of wild red corn poppies, a flower with a white edge. That was the beginning of 20 years of his hybridization work to get the characteristics he wanted with petals ranging from white through palest pink, lilac, cherry pink, apricot, salmon, scarlet, orange and bicolours as well as semi-doubles. They became known as the “Shirley poppies”. This is a montage I made of various strains and colours of P. rhoeas.

I love seeing the little Spanish poppy, Papaver rupifragum var. atlanticum ‘Flore Pleno’ in my travels. Also called Moroccan poppy or double Atlas poppy, there is usually a bee rolling around in the pollen-rich stamens. Despite its Mediterranean origins, it’s quite hardy and easily grown from seed.

Finally we come to the ‘type species’ for Papaver, the opium poppy, Papaver somniferum. That common name, of course, refers to the latex derived from certain botanical varieties of opium poppy being grown – either legally by the pharmaceutical industry, or illegally by the illicit drug trade – for naturally-occurring alkaloids such as morphine and codeine, among others. These are the “opiates” whose sedative and painkilling effects can also be highly addictive. “Somniferum”, the Latin epithet for the species means “sleep-inducing”. But most of the 52 botanical varieties of P. somniferum do not produce opiates. Czech blue poppy, though the same species name, is farmed for bread-seed, the little black poppy seeds you find on bagels and cakes. And many varieties were simply bred for ornamental purposes, not for medicinal or illicit drug manufacture. But if you want a history of the Opium Wars, etc., check out the Wiki page.

One beautiful cultivar of P. somniferum is ‘Lauren’s Grape’, below, my photo showing the glaucous, lettuce-like foliage of opium poppy. I photographed this lovely specimen in the Niwot, Colorado garden of Mary and Larry Scripter, which was designed by Lauren herself, Lauren Springer.

‘Cherry Glow’ is another beautiful opium poppy cultivar. I found a little Toxomerus geminatus hoverfly foraging on the pollen-rich stamens.

Sometimes you’ll see seeds offered for “peony-flowered” opium poppies, P. somniferum var. paeoniflorum. The cultivar below is ‘Flemish Antique’ and is quite famous in poppy circles.

And then there is P. somniferum var. laciniatum with its shaggy petals. I photographed the pretty duo below in my son-in-law’s mom’s farm garden in Alberta.

And now, finally, I come to the end of my long, long look at the diverse Poppy Family. With its silky white petals and bright yellow stamens, Romneya coulteri, Coulter’s matilija poppy or California tree poppy, is the tallest poppy family species I’ve photographed, growing up to 8 ft (2.4 m) tall and wide. Though I have seen this species in California, I photographed this one in the public garden in the Queenstown Gardens Park in New Zealand.