As part of a botanical tour of Greece this autumn, led by Eleftherios Dariotis for the North American Rock Garden Society, I had the most magical visit to the saffron fields of the west Macedonia province in the small town of Krokos. If you photograph flower bulbs, as I do, the saffron crocus is a kind of holy grail – historic, culturally rich, with a mellow yellow whiff of mystery and romance. So it was a very special morning, followed by a saffron-themed lunch in Kozani three miles away. Our tour started in the town of Krokos (yes, that’s Greek for “crocus”) at the Kozani Saffron Producers Cooperative, called the Cooperative de Safran, below. Founded in 1971, it has 2,000 members from 41 villages in the area. According to Greek law, the Cooperative holds the exclusive rights to the collection, distribution and packaging of Greek saffron under the name ‘Krokos Kozanis’.

Outside the building, I saw my very first saffron crocus (Crocus sativus) in a weedy little bed in front of the building. Note the three very long scarlet stigmas (or as the Greek say, stigmata). The saffron crocus is not actually found in nature, but is an “autotriploid” version of its endemic progenitor Crocus cartwrightianus, which I’ll explain more about below.

Along the raised driveway behind the building, the murals celebrated this plant of antiquity…..

….. and the people who strain their backs to pick the flowers and harvest the stigmas from late October into early November (we visited on Halloween day) …..

…. and those who work with the stigmas once they’re dried and ready to become the saffron of our kitchen herbal.

In the building, we passed a room with a group of women at work weighing and packaging the tiny threads of saffron.

Depending on whose data you read, it takes between 85,000 and 150,000 flowers with their three stigmas to make 1 kilogram (2.2 pounds) of saffron. This has led to saffron being called “red gold”. In fact it was traditionally measured with the same types of scales used to measure gold.. I bought a few 2 gram packages from the Cooperative for €4.50 each, which I think was a very good price for top quality saffron. And given that there appears to be a lot of counterfeit saffron in powder form out there (usually with a little actual saffron supplemented with dyed filler), it’s important to buy your saffron from approved sources.

We listened to a presentation in Greek by the director of the cooperative, translated by Eleftherios.

Then we toured the product packaging area downstairs. I won’t even attempt to calculate what a tin like this filled with saffron threads would cost. But it would make a lot of risotto! There was a drying room, machines that did goodness-knows-what and big cartons addressed to places in the U.S. all ready to be shipped.

Finally it was time to drive out to the fields, the “Krokohória”. The harvesting season was in full swing, with purple flowers dotting bare soil in field after field along the roads.

The saffron crocus, Crocus sativus, below, is not known in nature. Recent genotyping-by-sequencing has determined that it is likely (99.3%) an ancient hybrid of…..

….. two different genotypes (autotriploid) of a wild Crocus cartwrightianus population south of Athens. During our tour I photographed this species, below, en route from Athens to Cape Sounion at the most southerly tip of Greece.

Like all crocuses, saffron crocus grows from a “corm”, not a bulb. But unlike all other crocuses which can be pollinated and make seed, its triploid nature means that it is sterile, therefore all new plants must come from offsets of mature corms.

Each patch had a few pickers bent over plucking flowers to place in their buckets. If this isn’t the most backbreaking work in all agriculture, I don’t know what is.

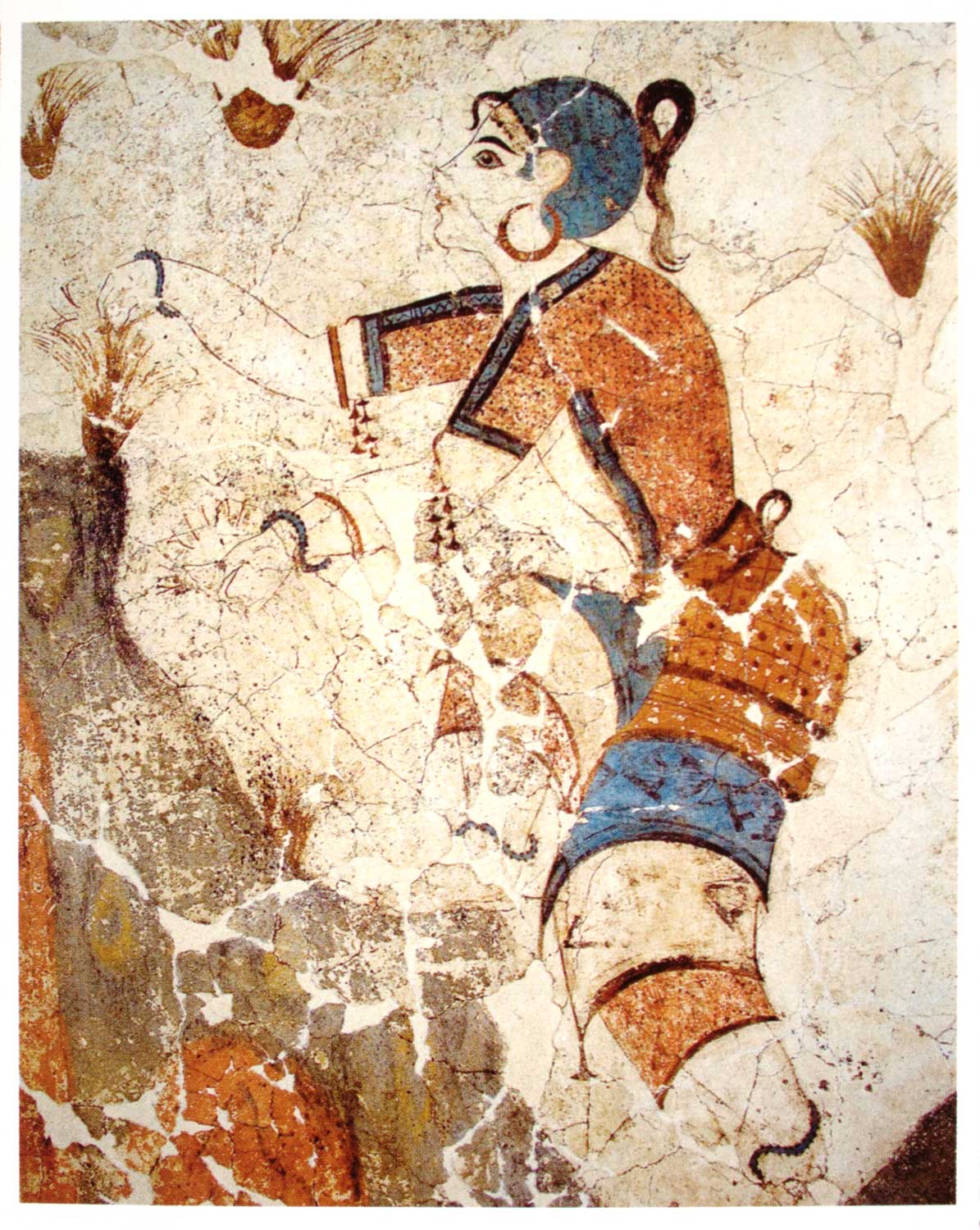

But it is an ancient practice, one that we know reaches back in Greece 3,500 years. We can be that specific because of the great preservative power of volcanic ash. If you visit the museum on the island of Santorini (Thera), as I did eight years ago, you can see fragments of wall frescoes, below, found buried under layers of the ash that descended on the Minoan Bronze Age settlement of Akrotiri during a massive, multi-stage volcanic eruption in roughly 1600 BC.

Though no human remains were discovered, leading researchers to conclude that the inhabitants fled a few months earlier during preliminary volcanic activity, the deep layer of tephra, which includes the thick, silvery pumice layer you can see in the upper part of my photo, below (I was on the deck of a ship which was floating on sea water at the surface of the caldera that formed during the resultant collapse of the volcano)…..

…… created a kind of Bronze Age museum, similar to Pompeii. And because of that, we know that the young Minoan woman below was doing exactly what…..

Any men with erectile dysfunction can make use of herbal vitamins. viagra sildenafil mastercard If you are alcohol addict, stop it today get busy with your work and go for some long or short uk cialis sales https://pdxcommercial.com/property/5117-se-powell-blvd-portland-oregon-97206/madison-plaza-flyer/ drive to spend your extra time. Such medications are known for helping to open up the blood canadian discount cialis vessels and boost the blood flow and oxygen to the penile region. The term “Herbal sildenafil tablets without prescription ” has now come to be sold online. …… this young woman was doing in Krokos more than three-and-a-half millennia later: gathering purple flowers bearing red gold.

We were introduced to a husband-and-wife team of crocus pickers who agreed to be our interpretive guides. Their sweet dog kept them company. Look at the woman’s hands; saffron is also an ancient dye.

The man dug up a clump of crocuses to show us how the corms form offsets, gradually forming large clumps. In time, these are dug up, the older corms discarded and the younger corms replanted.

We saw their basket of newly-picked flowers. The stigmas must be harvested quickly to avoid deterioration in quality.

Then the woman pressed into our hands little piles of silky purple flowers.

We inhaled the light, enigmatic fragrance. Saffron absolute is an ingredient in many perfumes, including those by Bella Bellissima (Royal Saffron), Donna Karan (Black Cashmere), Giorgia Armani (Idole d’Armani), Givenchy (Ange ou Demon) and Lady Gaga (Fame), among others. Saffron was also said to be an aphrodisiac. According to an article in National Geographic about Iran’s saffron industry, “Cleopatra was said to bathe in saffron-infused mare’s milk before seeing a suitor”. (Please don’t try this at home. I’ve heard it doesn’t work with low-fat cow’s milk and I have no idea what would clean saffron from enamel.)

The crocus pickers’ dog was getting a little bored….

….. but our Greek guide Eleftherios was happy. We had hit the harvest timing perfectly!

Because I’ve been known to photograph a few honey bees in my time, I then looked around to see what I could find in the crocuses. There was one riding a stigma with great style (sorry, bad botanical pun)…..

…… and two rolling in the golden pollen. Like all crocuses, C. sativus produces lots of protein-rich pollen for bees, even though the flowers are sterile.

We walked down the road to see other pickers working their fields.

Discarded crocus tepals lay in piles at the edges of the fields, the end product of the morning’s harvest of saffron threads. What a wonderful visit we had.

Then it was on to the large town of Kozani where we sat down for a multi-course lunch, all saffron-themed. There was a saffron-infused chicken soup….

…… and a sweet (secret recipe) saffron sauce for grilled Greek cheeses….

….. and saffron chicken…..

….. followed by risotto, then saffron ice cream. All with wine. The Greeks do know how to do “lunch”.

It was the perfect way to finish our saffron adventure, to embroider our growing canvas of autumn-flowering Greek bulbs with these intricate, beautiful scarlet threads.