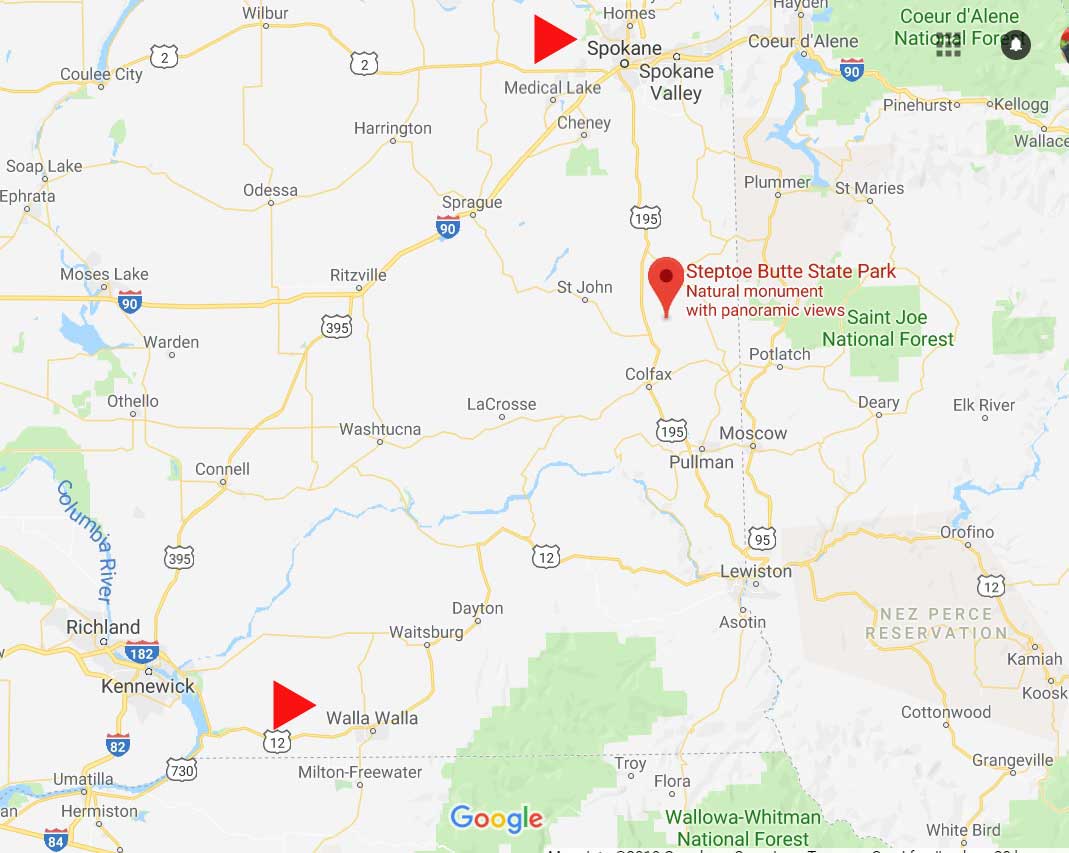

Normally, on the Friday of Canadian Thanksgiving weekend, I’d be making sure I had all the ingredients for a big family dinner: turkey, apples and pumpkin for pies, etc. But this year on October 6th my husband Doug and I were at the first stop on a 12-day road trip that would take us from Toronto east to Montreal, then south to Boston and Kennebunkport, Maine. In other words, we were at my favourite large botanical garden on the planet: Montreal Botanical Garden (MBG). And their pretty entrance display was evocative of autumn, Thanksgiving and Halloween!

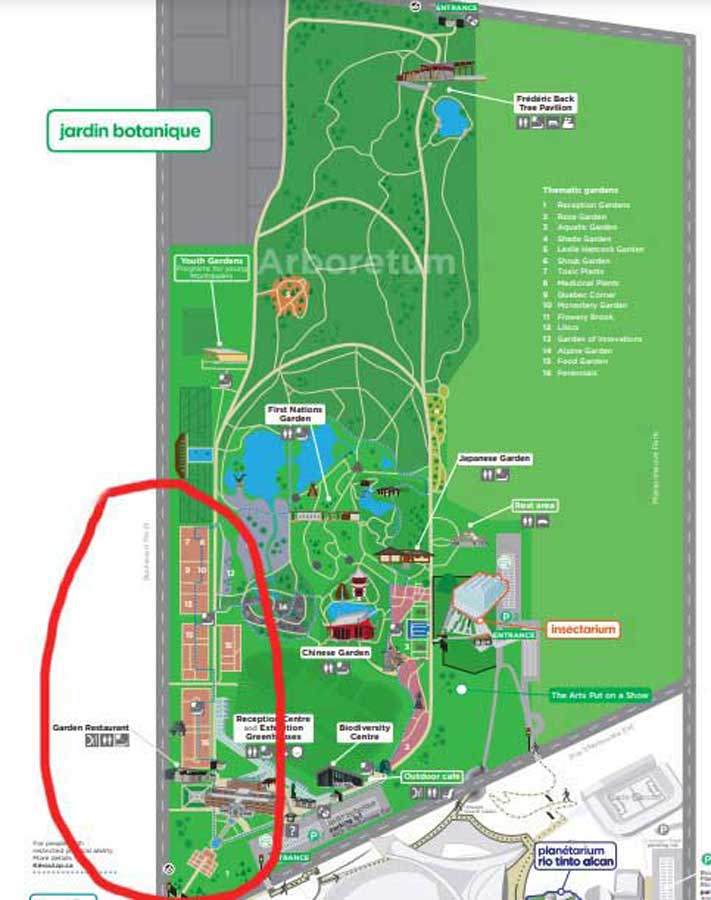

Before going further, let’s look at a map of the 185–acre (75-hectare) garden, which you can find online as a .pdf file here. The arboretum is filled with taxonomic collections of plants of all kind and there are Chinese and Japanese gardens and wonderful greenhouses filled with tropicals and desert plants, but because our time was limited, I chose to stay in the most densely planted part of the garden, which I’ve circled in red….

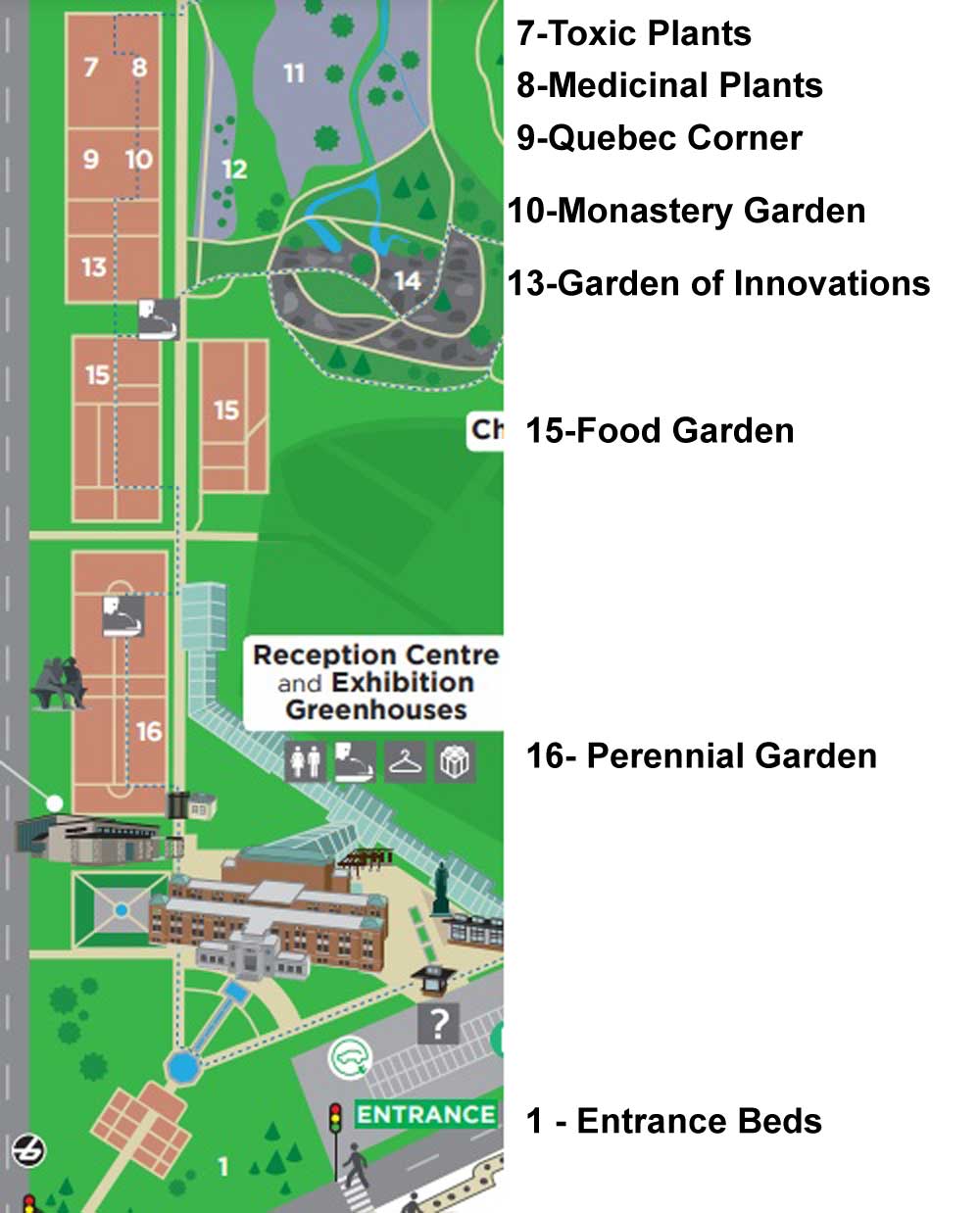

…. and enlarged and labelled below. (If I’d had more time I would have headed to the Shade Garden, which is always fabulous in its textural design and which I’ve blogged about previously, link at the end of this blog.)

Let’s start in the Perennial Garden, Jardin des Plantes Vivaces, with its long, geometrical layout. Dahlias were still looking good and the ornamental grasses were stunning.

Autumn colour was just beginning after our wet, cloudy summer in eastern Canada, but the Virginia creeper (Parthenocissus quinquefolia) was putting on a nice fall show in the long arbor.

The beds in the perennial garden are filled with treasures, though the spring- and summer-bloomers were now forming seeds. But I was interested that Geranium Rozanne was still flowering in the centre beds.

Grasses plus asters! Is there a better combination for October? This lovely purple-flowered aster was labelled Symphyotrichum novae-angliae ‘Cloud Burst’, which must be very rare because the only reference to it online is from the Royal Horticultural Society, which lists it as a New York aster with an unresolved name. But MBG is pretty good on taxonomy so I’m going to take their word.

This is a stunning, magenta-flowered New England aster with a compact form, Symphyotrichum novae-angliae ‘Vibrant Dome’.

Bumble bees, hover flies and honey bees were all over S. novae-angliae ‘Barr’s Blue’.

It was a pleasure to find more unusual asters in the garden, like the bushy aster Symphyotrichum dumosum ‘Pink Bouquet’….

… and native species, like old field aster, Symphyotrichum pilosum var. pilosum, below.

I had never come across this vigorous Japanese aster, Aster innumae ‘Hortensis’.

There were other late-blooming perennials, too, including Japanese anemones. The one below is Anemone hupehensis ‘Prinz Henrich’.

And for those who like hardy chrysanthemums, a beautiful display from Chrysanthemum Mammoth™ ‘Red Daisy’.

I’m accustomed to seeing calamint (Clinopodium nepeta) flowering profusely in summer and attracting tons of bees – but this level of bloom in autumn was unexpected. Was it cut back after initial flowering? What a great perennial.

Autumn monkshood is one of the best plants for October, but this cultivar fit the weather. Meet ‘Cloudy’ (Aconitum carmichaelii Arendsii Group).—and just as toxic as its azure-blue monkshood cousins.

I’ve never seen pitcher sage (Salvia azurea) standing upright, which is a shame. With that sky-blue colour, it would be the perfect autumn plant. Nonetheless, the bees love it.

And, of course, there are the big border sedums. This one is Hylotelephium ‘Autumn Fire’.

But the plants that really shine in autumn are the ornamental grasses, and Montreal Botanical Garden has a large selection. Below, Miscanthus sinensis ‘Berlin’ makes a lovely partner to ‘Fireworks’ goldenrod (Solidago rugosa).

One of my favourite effects in planting design, and one I’ve written about for a magazine (see ‘Sheer Intrigue’ in this American Gardener .pdf) is the use of grasses as screens, or scrims, or veils. In the pairing below, ‘Goldgehänge’ tufted hair grass (Deschampsia cespitosa) acts as a screen for blackeyed susans.

The tall moor grasses (Molinia arundinacea) make fabulous scrims, whether it’s the airy flowers or the stems, like ‘Skyracer’, below, in front of old field asters.

I was absolutely enchanted with this combination of northern sea oats (Chasmanthium latifolium) and ‘Dewey Blue’ switch grass (Panicum virgatum). And it made me wonder why some people say they don’t care for grasses in a garden!

I grow big bluestem (Andropogon gerardii) in my meadows at Lake Muskoka, but ‘Blackhawks’, below, is a dramatic cultivar of that native grass.

Positioned well, dahlias can add so much to perennial borders, like orange ‘Sylvia’ being graced by red Persicaria amplexicaulis ‘Firetail’ and an anise hyssop, likely Agastache ‘Blue Fortune’.

Bush clover (Lespedeza thunbergii) is a good semi-woody plant for early autumn; this is the cultivar ‘White Fountain’.

I was interested that MBG features a few of the knotweeds in the perennial garden. The one below is Himalayan knotweed, Koenigia polystachya, a perennial which has reportedly escaped into the wild on the mild Pacific coast.

And I don’t know whether the pink-flowered cultivar of Japanese knotweed, Reynoutria japonica ‘Crimson Beauty’, is as invasive as the straight species (some sources say it’s not), or whether MBG simply has the means and people power to keep it under control.

In the section that features interesting bulbs and luscious swamp hibiscus (H. moscheutos), I was intrigued by the fall colour on the burgundy-leaved cultivar ‘Dark Mystery’, whose foliage had turned apricot, orange and gold.

The Food Garden was mostly finished, but the grains section looked vibrant. The amaranths, in particular, are varied and attractive. The one below is Amaranthus tricolor ‘Elephant’s Head’ — an excellent likeness, right?

Okra is as pretty in flower as it is a valuable edible. The one below was labelled Abelmoschus esculentus ‘Motherland’, but in researching okras online, I discovered this on a page from SowTrue Seeds called “Field Notes: The Utopian Project”. “Beyond the myriad okra varieties is a row of several closely-related species that are not actually okra but its cousins, if you will. Most of these don’t produce edible pods, but some do. A surprise and a historical mystery is hiding among those cousin species. It’s a bushy plant with huge leaves bigger than an open-spread hand. This variety is called Motherland okra, and it has been stewarded by Jon Jackson of Comfort Farms in Millegdeville, GA, whose family got it from West Africa. As the plants started to produce blossoms, Chris noticed that they resembled those of a couple of other unusual-looking okra varieties, one of which is Mayan okra. While most okra Southerners are familiar with is of the species Abelmoschus esculentus, and varieties of this species are also found all over Africa, India and Southeast Asia, Chris believes Motherland, Mayan, and this one USDA accession are actually Abelmoschus callei, a similar but distinct species originally endemic to West Africa. He wonders how many other A. callei varieties are out there hiding in plain sight, just considered to be okra like all the others.”

There are borders devoted to edible flowers, like this nasturtium, Tropaeolum minus ‘Bloody Mary’…..

….. and this inspiring combinations of herbs and vegetables with edible flowers, like the common fennel (Foeniculum vulgare) and purple ‘Redbor’ cabbage with the playful pink pompoms of annual Gomphrena globosa ‘Firecracker’.

The Food Garden includes plants from the four corners of the world, including this dwarf tamarillo with its unripe fruit, Solanum abutiloides, which will turn orange eventually.

The Herb Garden looked past its prime, but I was interested in this basil, which despite its Latin name, Ocimum americanum, is actually from Zambia.

The Garden of Innovation features newly-introduced annuals, perennials and tropicals….

…. including many award-winners, like the Perennial Plant Associations’ 2023 Plant of the Year, Rudbeckia ‘American Gold Rush’, from my friend, plant breeder Brent Horvath of Intrinsic Perennials. Though it’s past its prime, keep in mind that this is October 6th, long after most blackeyed susan species and hybrids have finished blooming.

Much of this garden is devoted to annuals, such as this petunia with the tiniest flowers, P. x atkinsiniana ‘Itsy Pink’.

New coleus introductions, such as Coleus scutellarioides ‘Talavera Burgundy Lime’, show off the remarkable colour combinations and adaptability of this foliage annual.

Breeders worked hard to get bearded iris to re-flower in autumn, after their June debut. This one is aptly-named ‘Lovely Again’.

I ducked under the arch wreathed with Virginia creeper to peek into the Quebec Corner garden, which looked much like the natural woodland around my Lake Muskoka cottage. However, with time passing and lunch calling, I started to exit before catching a movement in a serviceberry nearby.

And there was a bird I know mostly by its song — at Lake Muskoka we call it the “Oh Canada bird” (Oh Canada-Canada-Canada!): the white-throated sparrow (Zonotrichia albicollis).

Sadly, there was no time to explore the Shrub & Vine Garden, but I managed a quick look at a few beautiful hydrangeas, including H. paniculata Limelight Prime…

….and H. macrophylla Endless Summer Twist-n-Shout.

In all the years I’ve visited gardens, in North America and around the world, I’ve often been accompanied by my husband, Doug. As I approached his chair overlooking the pond near the peony and iris collection, I recalled him waiting for me (sometimes reading his book) at the Keukenhof in the Netherlands; Dutch designer Piet Oudolf’s garden at Hummelo; Kyoto Botanical Garden; the Orto Botanico in Palermo and Rome; the Jardin des Plantes in Paris and Monet’s Giverny; Savill Garden, Hampton Court, Sissinghurst and many others in England; Chanticleer near Philadelphia; Garden in the Woods and New England Botanical Garden near Boston; Seaside Gardens in Carpinteria, California; Los Angeles County Arboretum; Fairchild Tropical Garden in Miami, and many, many more. He is often my chauffeur and I’m the terrible map reader (much easier with GPS now); he enjoys being in all the gardens and patiently waits for me to finish my photo shoot. So thank you, Doug.

But he did want to have lunch, so we walked back to the restaurant near the entrance where I noted the gorgeous hanging basket of begonias.

Then it was off towards the Pie-IX subway stop just a block away to head back to our hotel. We walked past the entrance gardens, still looking superb….

…. with their mix of colourful annuals, always one of my favourite examples of plant design. And, as always, I gave thanks (on Thanksgiving Weekend, no less) that I had the opportunity to enjoy the excellence that is the Montreal Botanical Garden.

********

Interested in reading more about the wonderful gardens of Montreal Botanical Garden? Here are three of my previous blogs: