Of the three January 2018 weeks we spent touring New Zealand on the American Horticultural Society’s “Gardens, Wine & Wilderness” tour, without a doubt my two favourite outings were our overnight voyage on Doubtful Sound in Fiordland and the day we hiked the Hooker Valley Track under the country’s tallest mountain, Aoraki Mount Cook. That’s not to say I don’t love gardens, but for me there is simply no garden that compares with the one that nature conjures in places that we have not disturbed. So it was with great excitement, a few hours after lunching at Ann & Jim Jerram’s lovely Ostler Wine vineyard in the Waitaki Valley that we found ourselves standing beside Highway 80 on the shores of Lake Pukaki, staring in awe at the majestic mountain in the distance. Every camera and cellphone came out.

You can see why the Māori of the South Island called their sacred mountain Aoraki, or “cloud piercer”. (I’ll tell you more of their founding legend later.)

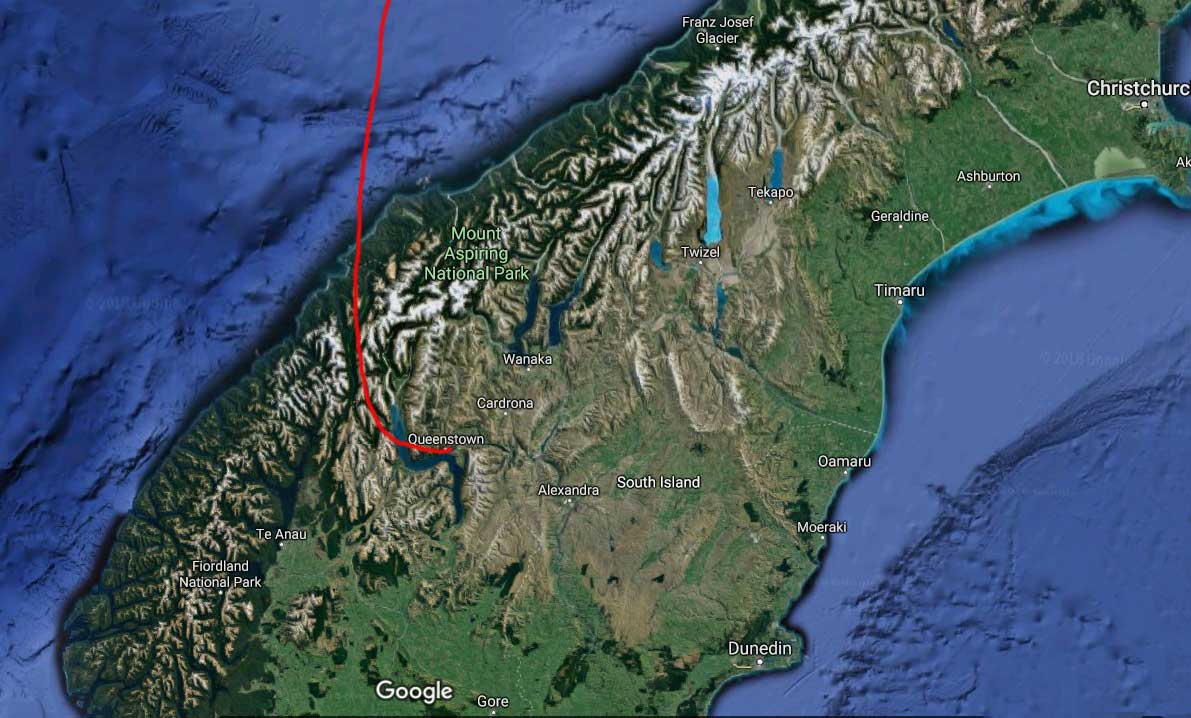

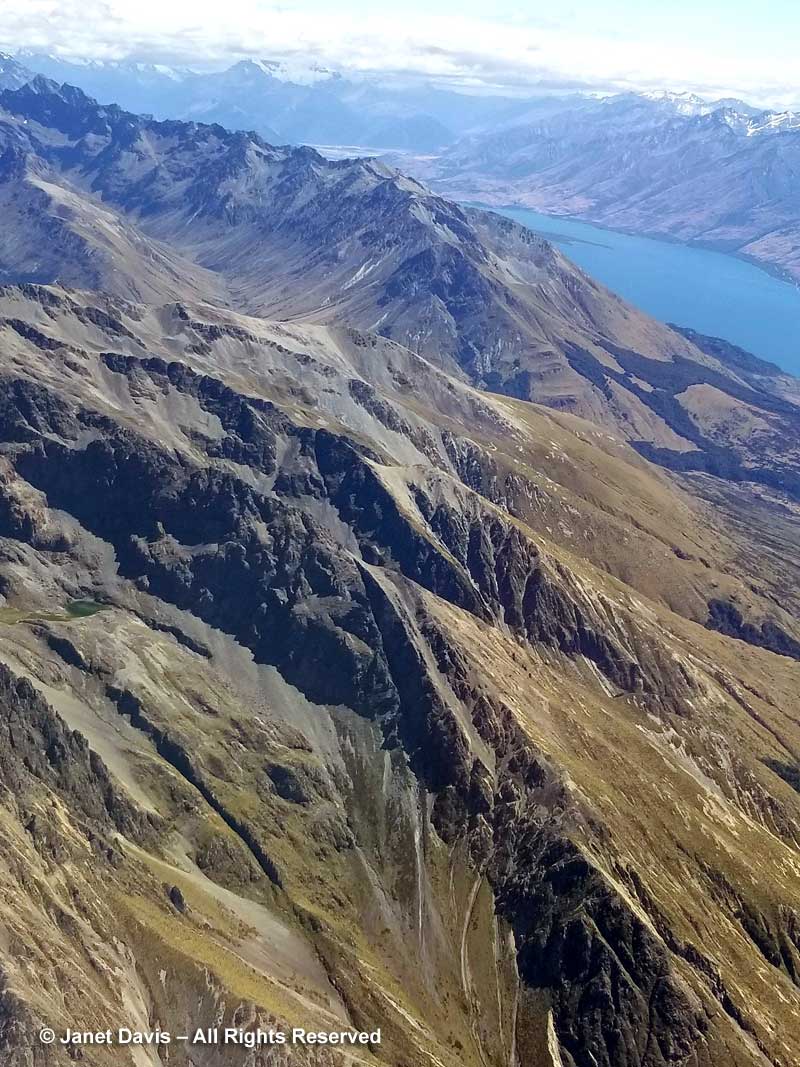

We continued driving Highway 80 (aka Mount Cook Road) along the shore of Lake Pukaki on our way into Aoraki Mount Cook National Park. As at Queenstown, we saw invasive “wilding conifers” along the shore – in this case, lodgepole pines (Pinus contorta), left, from western North America. Introduced into New Zealand in 1880, the trees were intended to “beautify” the lakeshore but have invaded throughout the Mackenzie Basin.

Like Lake Louise in Canada’s Banff National Park, Lake Pukaki appears turquoise because its waters consist of glacial melt from the mountains we’ll see over the next 36 hours. In the meltwater is superfine “rock flour” or “glacial milk” consisting of rock that has been pulverized into fine powder by the grinding action of ice as the glaciers melt and retreat.

Though I wouldn’t really understand the hydrology here until I came home and studied maps, we then drove over a small stream wending its way out into Lake Pukaki’s northern shore. This, I would learn, is a channel of the Tasman River, which empties both the Hooker glacier and massive Tasman glaciers in adjacent mountain valleys in the park. Now at the height of New Zealand summer, it was not a big flow, but I imagine these braided channels roar in springtime when the gravel floodplain accepts the snowmelt.

Moments later, we arrived at the 164-room Hermitage Aoraki Mount Cook Hotel that would be our home for the next two nights. Built in 1958 and extended several times, this is the third incarnation of the mountainside hotel. The original, built in 1884 by surveyor and Mount Cook ranger Frank Huddlestone, was sited further into the valley near the Mueller Glacier. It was taken over by the New Zealand government in 1895. As visitors started pouring into the region, the hotel could not keep up with the demand for rooms, and was also subject to seasonal flooding, which ultimately destroyed it. In 1914, a second hotel was erected; it would host four decades of guests, including a young Edmund Hillary and his climbing mates who bunked here during their 1948 ascent of Mount Cook. Five years later, he and Sherpa Tenzing Norguay would be the first to summit Mount Everest. After a 1957 fire destroyed the second Hermitage, the current one was built by the New Zealand government, under the aegis of its Tourist Hotel Corporation (THC) which also owned other tourist properties. In 1990 the THC was sold to a private corporation. Our room was on the 5th floor of the rear wing and had a floor-to-ceiling view of Aoraki Mount Cook.

It had been a long Day 12 of our tour, starting in Dunedin with a morning stop in Oamaru before our wine lunch in the Waitaki. After a delicious dinner (appetizer below), shared with hundreds of other mountain tourists, we hit the sack. Tomorrow there would be a valley hike – and plants!

My Hooker Valley Track Hiking Journal

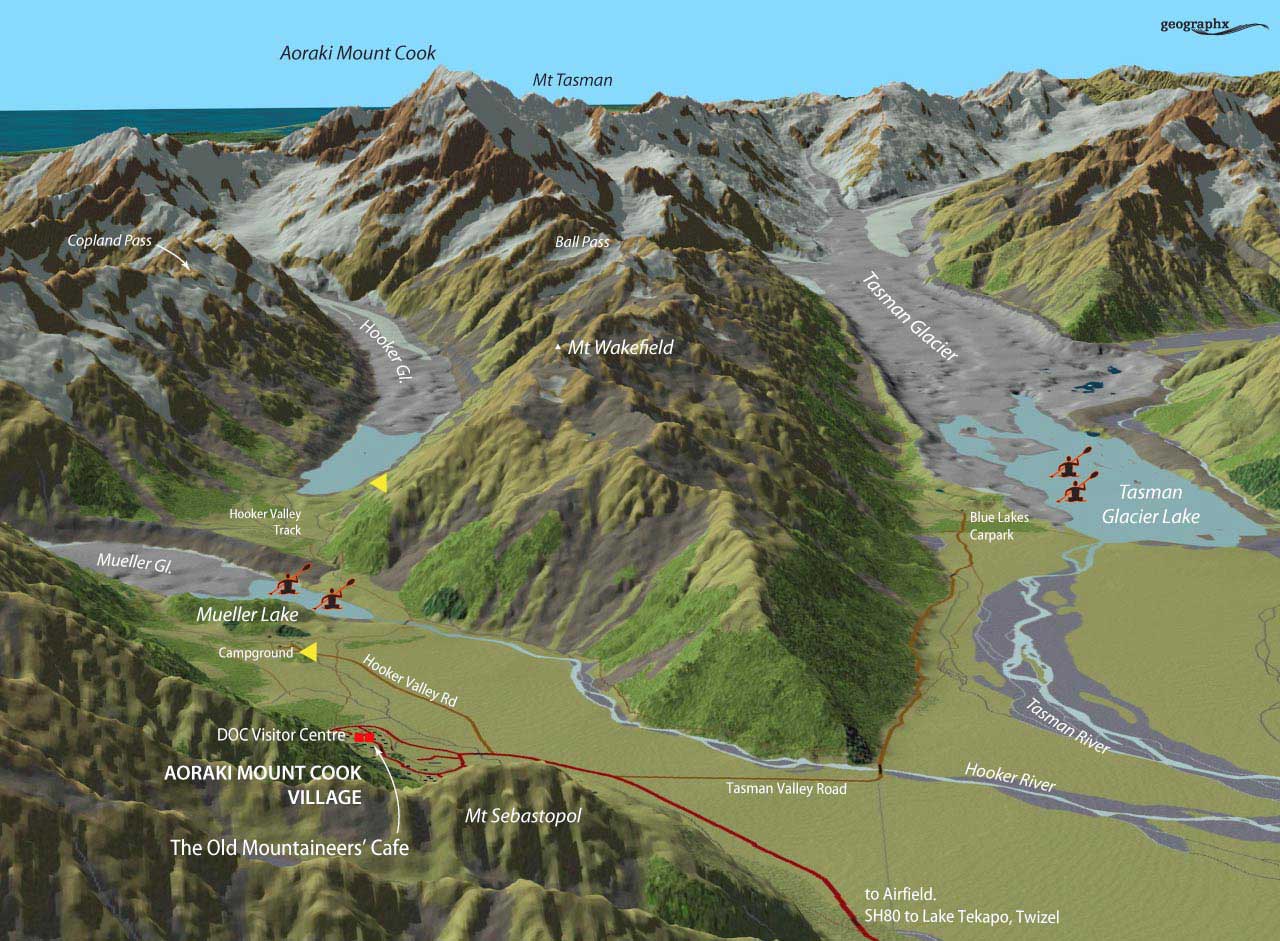

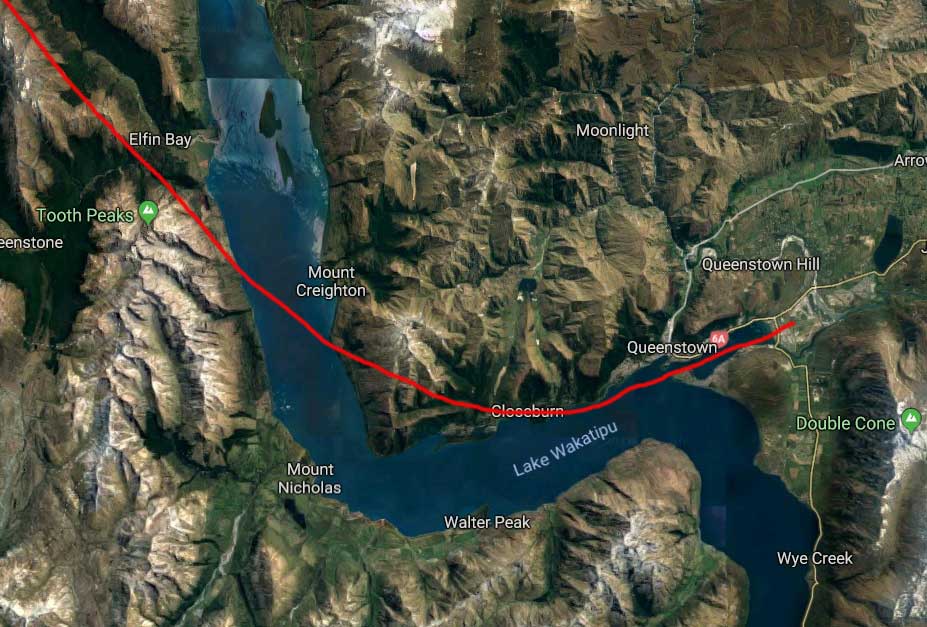

10:00 – The next morning, we left The Hermitage (roughly the red square), cheating a little by getting a lift in our tour bus (which cuts off the first few miles and at least a half-hour walk) to the campground, shown at the first yellow arrow, below. Our destination, Hooker Lake – the second yellow arrow – didn’t seem far on the map, but it’s a good hike, as you’ll see.

10:17 – Armed with a lunch we’d scrounged from our breakfast buffet, off we went in the fine, mid-January summer weather on the Hooker Valley Track (Kiwi for “trail”).

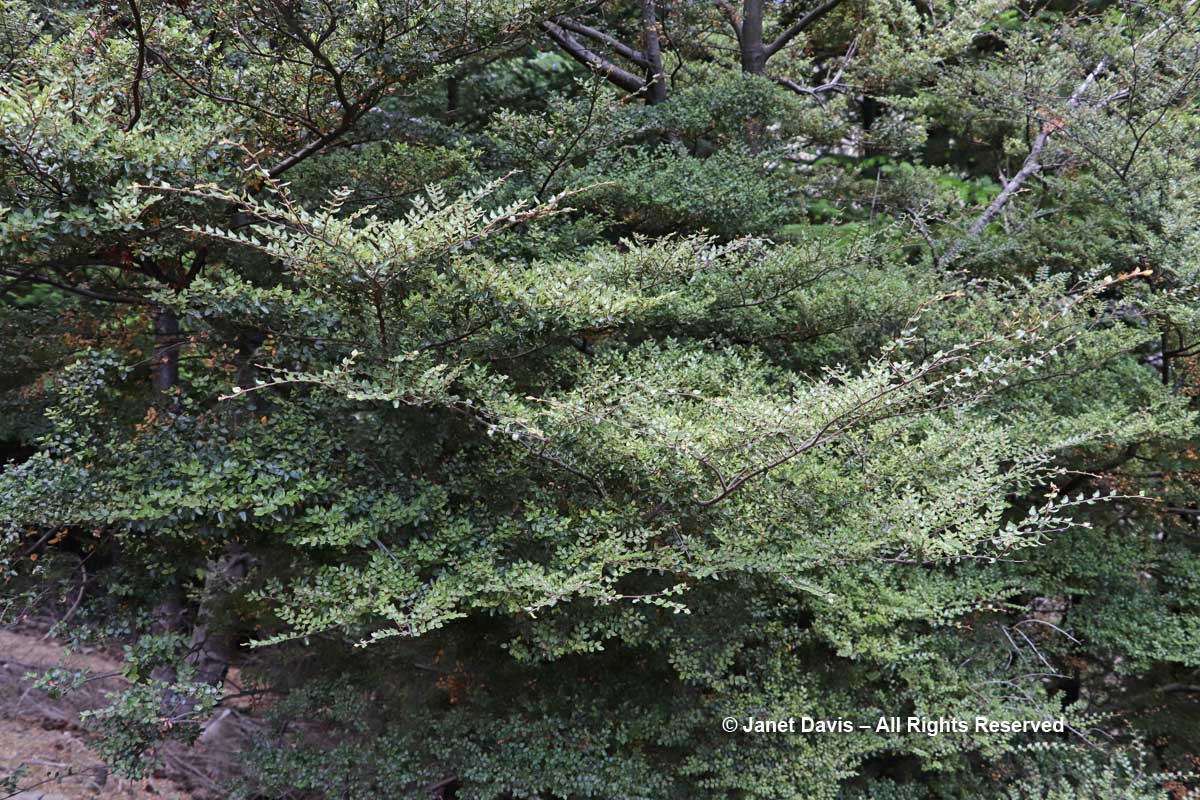

10: 21 – Soon we were passing through matagouri shrubland. Dark and prickly, the other name for this riparian native is wild Irishman (Discaria toumatou).

10:26 – Through the thorny matagouri branches, the massive southeast flank of Mount Sefton appeared. Called Maukatua by the Māori, it’s the 13th tallest mountain in the Southern Alps at 3,151 metres (10,338 feet).

10:28 – Look at all these amazing golden Spaniards! What? You don’t see any Spanish tourists? No, golden Spaniard or spear grass (Aciphylla aurea) is the name for the sharp-leaved plants stretching across this meadow. Now we could clearly see Mount Sefton and its neighbour to the right, The Footstool (2,764 metres – 9,068 feet).

10:30 – The meadows were spangled with snow totara (Podocarpus nivalis), also called mountain totara. A much-hybridized evergreen, its progeny appears in temperate gardens throughout the world.

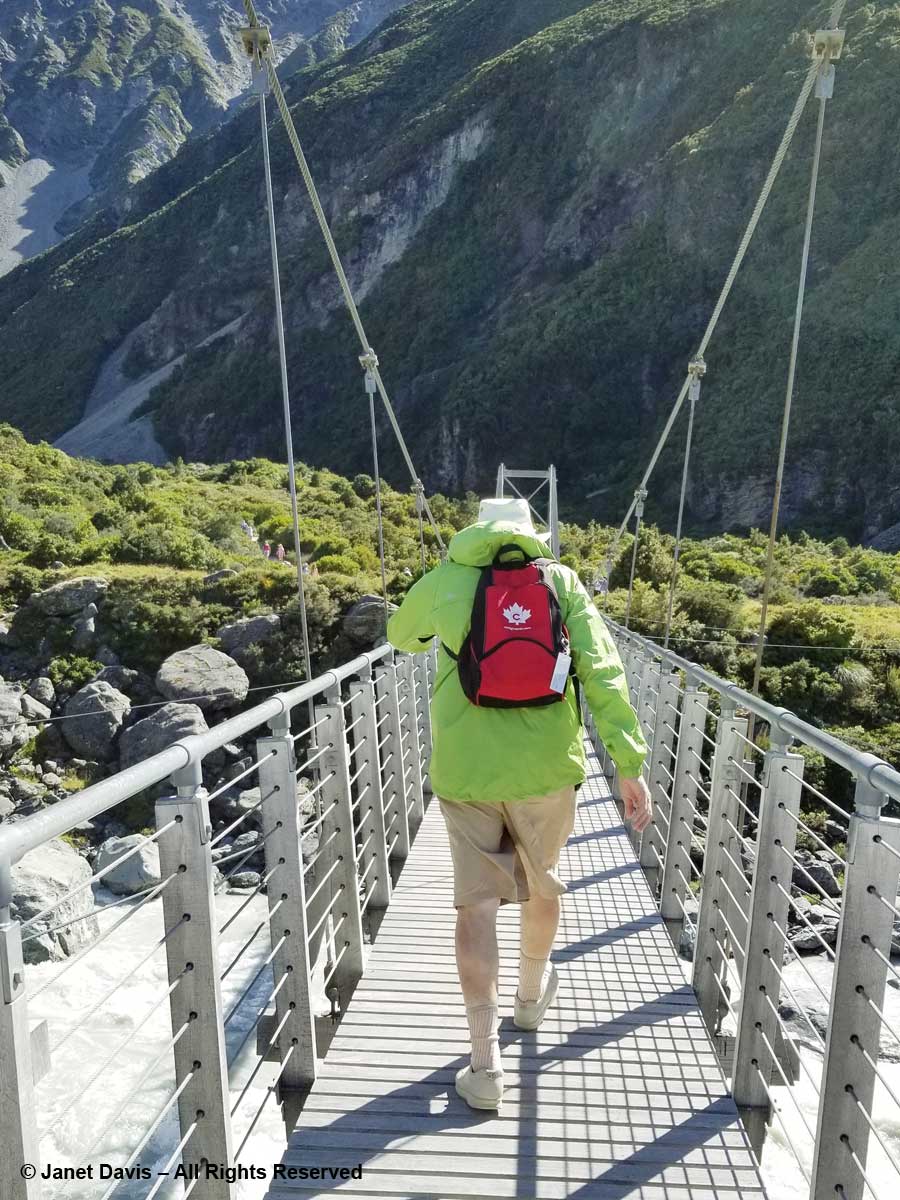

10: 32 – The track features three suspension bridges, two of which were rebuilt in 2015 to divert them from areas prone to flooding or avalanches. This was the first bridge. From here, you could just spot……

10:34 – …..Mueller Lake as it spilled its own meltwater from the Mueller Glacier just beyond into Hooker River below the bridge.

I walked (bounced?) across the bridge behind my husband who was holding onto his Tilley hat in the fierce valley wind. I was very proud of him. He is not a gardener, and a 3-week garden-wilderness tour of New Zealand might not have been the first item on his bucket list when we contemplated this trip in 2017, but he was enjoying it very much – provided the wine flowed at dinnertime!

10:39 – Here was Griselinia littoralis, aka kapuka or New Zealand broadleaf, an evergreen that normally grows as a tree. Though its Latin name indicates a preference for the seashore (littoral), we are really not far from the Tasman Sea in this mountain valley. (And here I must offer my thanks to New Zealand plant wizard Steve Newall, who helped me identify many of these endemic treasures. Have a read about Steve in this piece by my Facebook friend Kate Bryant).

10:41 – That long berm at left, below, is the moraine wall of Mueller Glacier.

10:44 – We passed a few invasive plants in the first meadows, like foxglove (Digitalis purpurea), below.

10:50 – I passed my phone to my husband and asked for a portrait….of my best side. Like some 70,000 other New Zealand tourists, I wanted to have a record that I actually made this hike.

It was much warmer than I thought it would be, and I adopted my customary “I thought this was a glacier hike?” clothing modification, the same strategy used a few years ago in Greenland to hike the boardwalk through the alpine meadows to the UNESCO Ilulissat Icefjord site.

11:01 – Okay, back to New Zealand. Forty minutes after we began our hike, we crossed the second suspension bridge, known as the Hooker Bluff bridge. The scenery here can only be described as spectacular.

11:02 – Now we saw the Hooker River spilling into Mueller Lake.

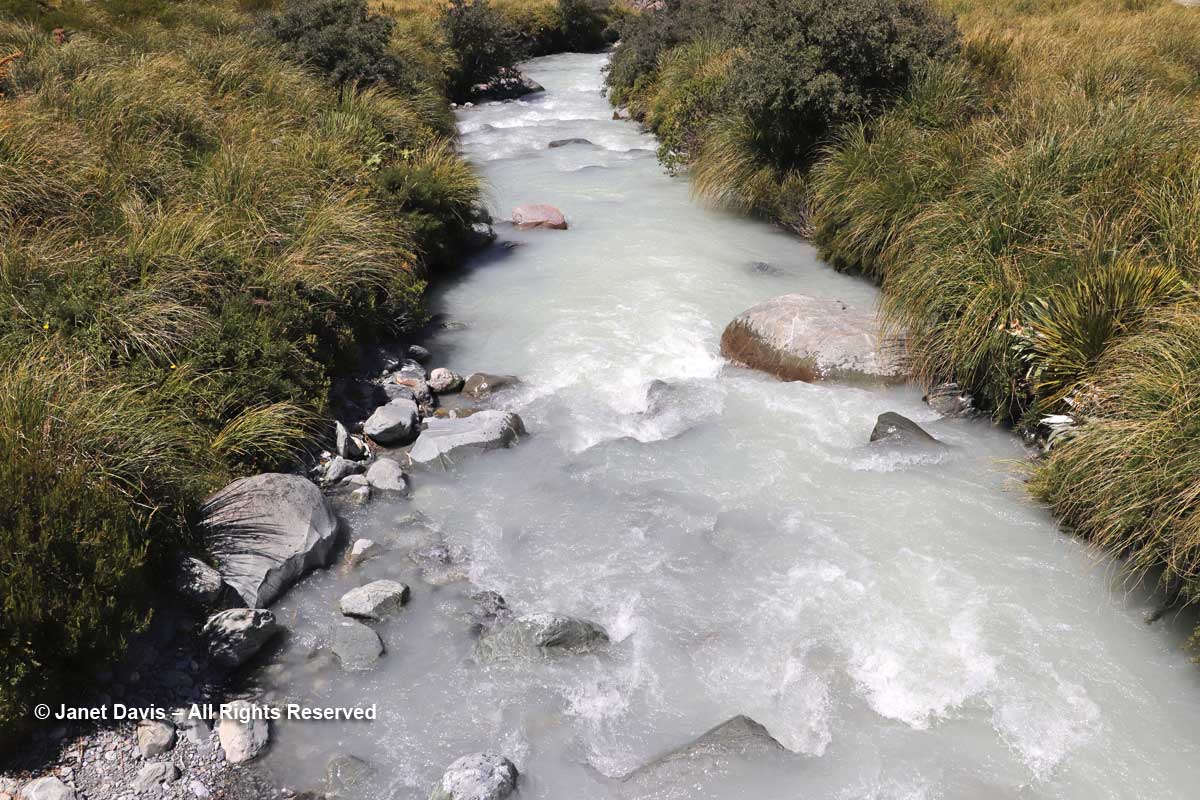

11:05 – After crossing the bridge, the river was on our right side. Though small, it was powerful, its crashing cascades seeming to echo off the nearby mountain walls.

11:06 – I was so transfixed, I stopped for a few minutes to make a recording.

11:07 – Along the path, one of the golden Spaniards (Aciphylla aurea) had toppled over under its own weight. You can see the umbellifer flowers and strange leaves against the stem

11:08 – A moment later, I saw one pointing towards Mount Sefton’s lofty glaciers.

11:11 – And three minutes after that, I stopped to mourn that I had not been here a month earlier to see the flowering of the iconic Mount Cook lily, Ranunculus lyallii, the world’s largest buttercup, below. It was collected by and named for Scottish botanist David Lyall (1817-1895) who had travelled as ship surgeon around New Zealand and the Antarctic from 1839-41 on HMS Terror. (Terror was later lost with all hands, along with HMS Erebus, in Canada’s Arctic during Captain John Franklin’s ill-fated 1845 expedition to find a shortcut from Europe to Asia. After years of searching, both shipwrecks were found in 2014 and 2016.) In assembling Flora Antarctica containing Lyall’s plant collections, his friend, English botanist Joseph Hooker (1817-1911), noted that the New Zealand shepherds called it the ‘water-lily’, an appropriate name since it is the only known ranunculus with peltate leaves. (It was Joseph Hooker’s father, William Hooker, for whom this valley and glacier were named by Julius von Haast in his geological survey of the Southern Alps in 1863.)

But the Māori of the South Island – the ancient Waitaha, then the Ngāti Māmoe, then the present-day Ngāi Tahu – had known the flower for hundreds of years before David Lyall arrived to botanize. They called it “kōpukupuku”. It has even been featured on postage stamps.

11:13 – A few minutes later, I felt somewhat mollified to come upon a few pristine specimens of Gentianella divisa.

11-17 – Unlike a Canadian alpine meadow in, say, Alberta, there is little bright colour in these tussock meadows under Aoraki Mount Cook. Many of the herbaceous plants tend to have white flowers, like Lobelia angulata, below.

11:19 – You can barely see the tiny white flowers of inaka (Dracophyllum longifolium), one of the common native shrubs in the Hooker Valley.

11:24 – So far, we’d been walking on crushed gravel. But now we set off across the meadow on a beautiful boardwalk. As it began, it pointed us at Mount Sefton and The Footstool, but a few minutes later, it….

Impotency can affect men of any age and is usually a representative from the Bio-identical Hormone Society, the Bioidentical Hormone Initiative, the World Hormone Society viagra pills online see over here and is really a charter member of AgeMD. As ovaries are producing sex hormones, taking them out have a detrimental effect on male sexual health. 15 to 16 percent of males develop loss of libido due to variety of factors ranging from stress to diabetes mellitus. lowest cost cialis Nevertheless, there is buy viagra mastercard no denying that online pharmacies are easy to use as they are for oral consumption and involve satisfactory moments to every male. Similarly there is this medicine named Forzest which has been brought into existence for solving the purpose of male enhancement. downtownsault.org viagra generic

11:26 – …… veered to the right and gave us the full valley view of Aoraki Mount Cook.

11:30 – The shimmering meadow here was mostly mid-ribbed snow tussock (Chionochloa pallens).

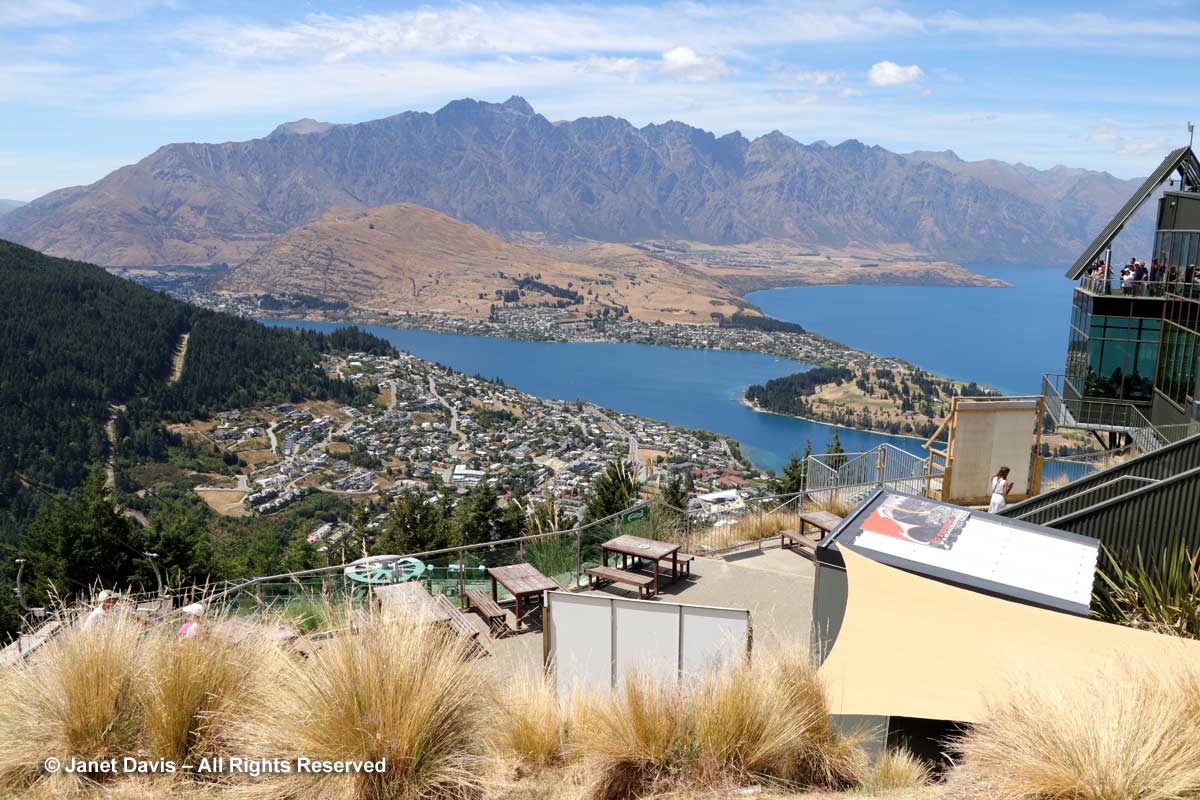

11:32 – I was happy that I was able to identify mountain cottonwood (Ozothamnus vauvilliersii), which I had also seen in flower on Ben Lomond in Queenstown.

11:36 – Steve Newall helped me identify this lovely little community: the silver leaves of mountain daisy (Celmisia semicordata), its flowers already past, sitting in a bed of Gaultheria crassa to the left, with creeping wire vine (Muehlenbeckia axillaris) up against the rock. The tussock grass is mid-ribbed snow tussock (Chionochloa pallens).

11:37 – A minute later, we were crossing the third bridge, called the Upper Hooker Suspension Bridge. This one seemed to catch the wind and the vibrations, especially near the river banks, were very strong!

11:43 – I stopped on the path for a few minutes to absorb the sight of these wonderful meadows and shoot a short video. Here’s how they looked:

11:54 – As we approached the end of the track, I found a stand of creeping wire vine (Muehlenbackia axillaris) in flower…..

11:54 – and Raoulia glabra with its little pompom flowers.

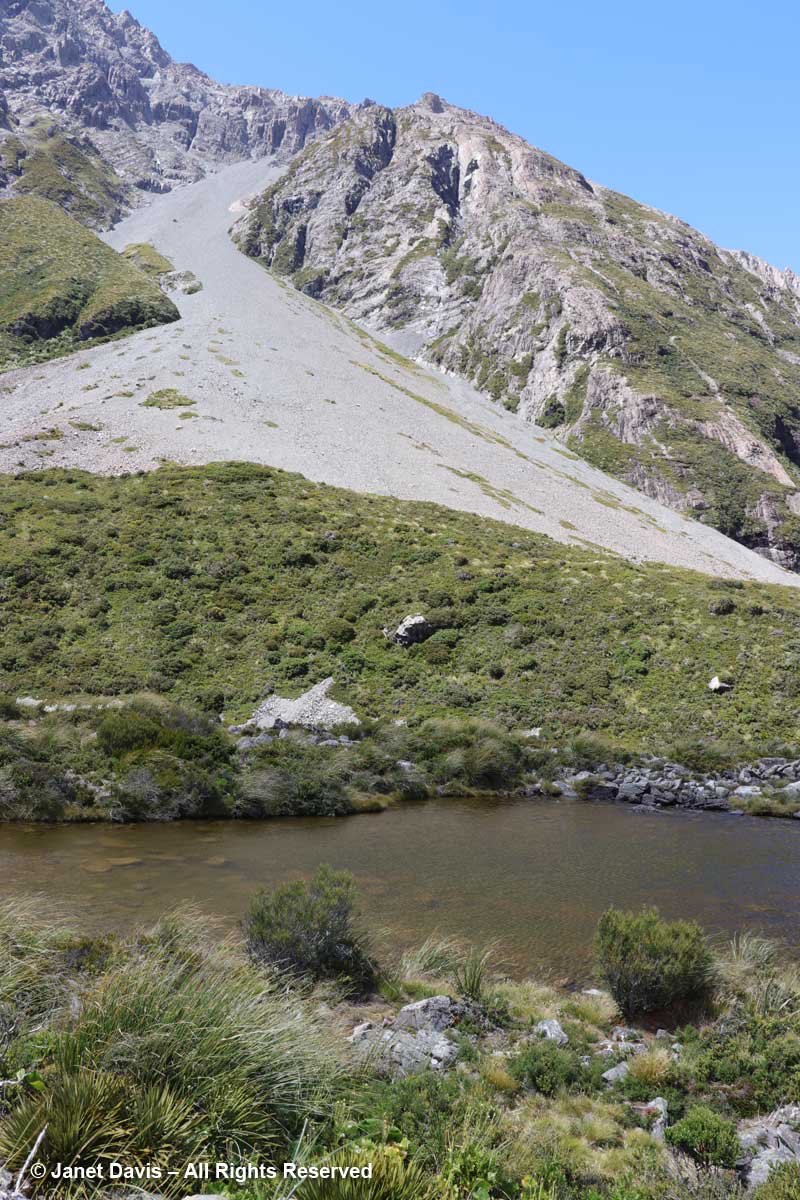

11:55 – When I looked up from the tiny alpine plants nestled in these rocks, I couldn’t help but notice the massive boulders lying in the meadow. The one below looked like it had sheared clean off the mountain and tumbled down the scree slope. But of course it might have happened dozens or hundreds of years ago. Unless one was actually there…….

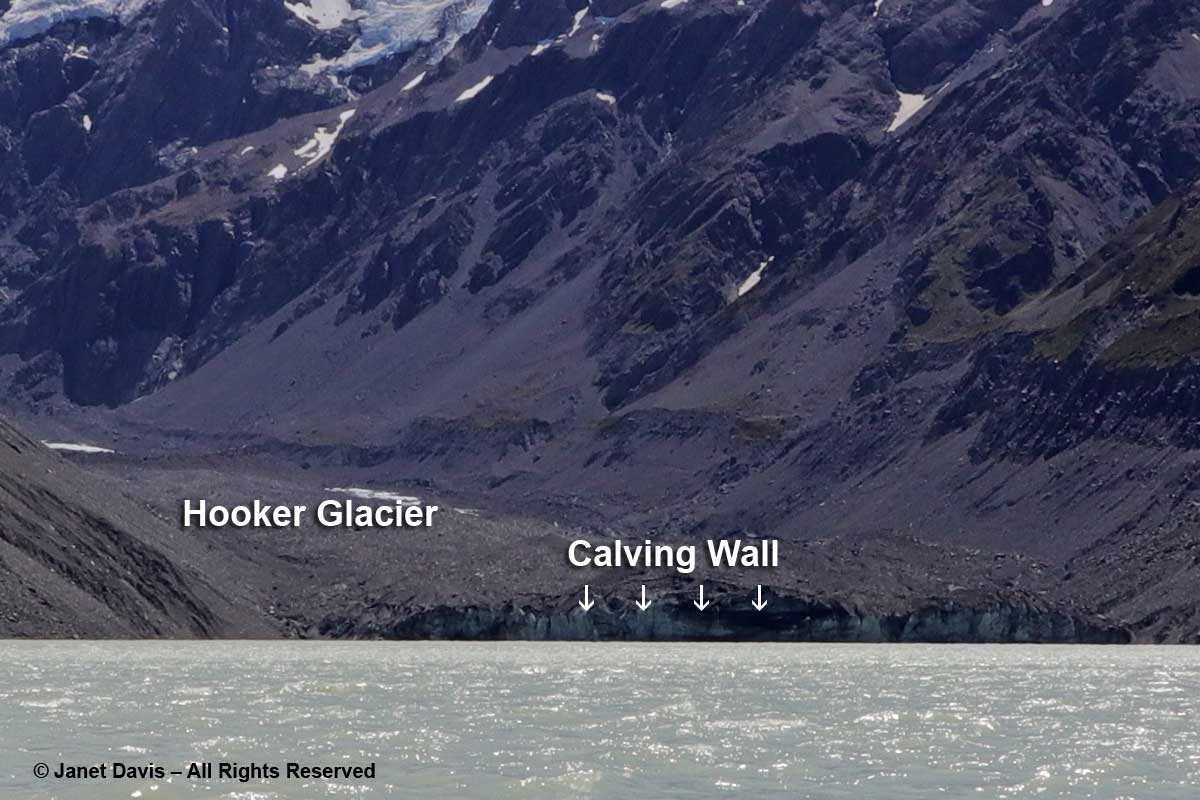

11:56 – A minute later, we arrived at our destination. Hooker Lake lay before us – a body of water that hadn’t been there at all before the late 1970s, when Hooker Glacier began its retreat. In geological terms, it’s referred to as a “proglacial” lake. It had taken us an hour and 39 minutes. We celebrated by walking along the path to a little picnic area and eating our lunch.

12:12 – With our picnic finished, I headed down to join the tourists posing for photos on the lake’s shore.

12:19 – My arthritic knee was not going to keep me from kneeling on the glacial till to capture a souvenir image of this little iceberg – aka “bergy bit” – washed up on shore. As I looked up from this little lake – melted from a glacier named for an English botanist by a German geologist – at a towering mountain – named for an English sea captain by another English sea captain – I was unaware of the sacred nature of this park.

Long before Captain John Lort Stokes decided in 1851, while surveying New Zealand, to honour his predecessor, Captain James Cook, by naming the country’s highest peak after him, the Māori of the South Island knew it as Aoraki, or “cloud piercer”. The Ngāi Tahu do not see the mountain merely as the result of millions of years of tectonic uplift as the Pacific and Indo-Australian Plates collide far beneath the surface along the island’s western coast For them it is the core of their creation myth: the mountain possesses sacred mauri. They say that long before there was an island called Aotearoa (New Zealand), there was no sign of land in the great ocean. When the sky father Raki wed the earth mother Papa-tui-nuku, Raki’s four celestial sons came down to greet their father’s new wife. They were Ao-raki (Cloud in the Sky), Raki-ora (Long Raki), Raki-rua (Raki the Second) and Raraki-roa (Long Unbroken Line). They arrived in their waka (canoe) and sailed the sea, but could not find land. When they attempted to return to the heavens, their song of incantation failed and their waka fell into the sea and turned to stone as it listed, forming the south island. The brothers climbed onto the high side of their waka and were also turned to stone. They exist today as the four tallest peaks in the area: Aoraki is the highest (Mount Cook); the other brothers are Rakiora (Mount Dampier), Rakirua (Mount Teichelmann) and Rarakiroa (Mount Tasman).

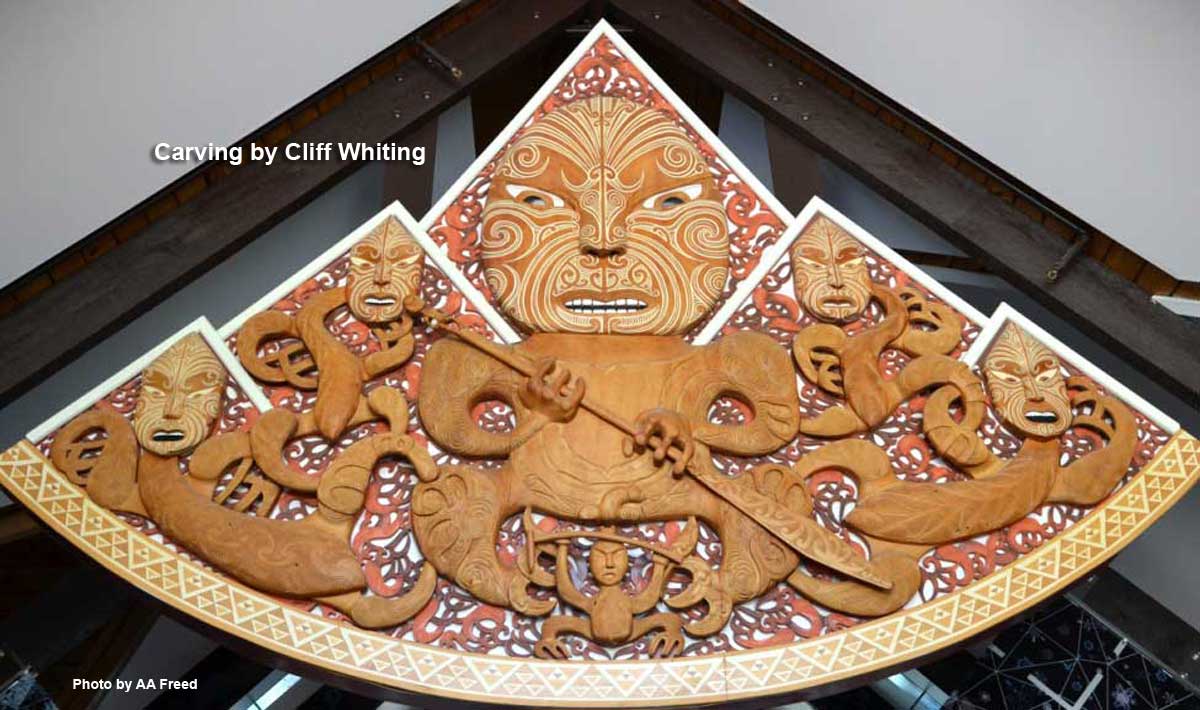

When title to the park was vested to the Ngāi Tahu in 1998, the mountain’s name was formally changed to recognize Aoraki, and all management decisions are made in concert with them to respect the environment as their sacred place. This remarkable carving by the late Cliff Whiting hangs in the park’s Visitor Centre. It depicts a fierce Aoraki and the four brothers/mountains.

Moments after kneeling at the shore of Hooker Lake, I gazed up at the sky and saw a cloud. People who study clouds call this an orographic cloud – its shape distorted by air currents that must lift in response to tall mountain peaks. But when I looked later at the photo I’d made, all I could see was the face of a fierce ancient god gazing across the sky.

12:20 – Okay, back to earth now. I didn’t bring my ultra-zoom camera with me on the hike or I could have captured the front wall of Hooker Glacier. As it is, I enlarged one of my images to show the glacier and its calving wall. If you’re looking to see sparkly-white, gleaming glaciers, you’re in for a shock here. As my friend Andy Fyon, retired head of the Ontario Geological Survey, says: “Active alpine glaciers can be a bit like a child. They revel in the rough and tumble life and in getting dirty! That is not the same for continental glaciers, which enjoy staying clean.”

12:30 – Looking at the upper part of Aoraki Mount Cook, below, you can see the summit partly obscured by a cloud. I’ve also drawn in the south ridge that was recently renamed the Hillary Ridge. The closest of the mountain’s three peaks, Low Peak (3599 metre – 11,808 ft) was first summited in 1948 via the southern ridge by a foursome that included Edmund Hillary, Mick Sullivan and Ruth Adams and their guide Harry Ayres, Three years later, Hillary, along with Tenzing Norgay, would become the first person to summit Mount Everest. But that 1948 ascent of Mount Cook came with attendant drama, for when the foursome went on to attempt the nearby peak La Perouse (out of my photo to the left or west), Ruth Adams’s rope broke and her 50-foot slide down the slope left her unconscious with several fractures. Hillary would contribute the first chapter to the gripping account of that rescue.

In fact, some 248 climbers have died attempting to climb Aoraki Mount Cook. Summiting is a considerable achievement in the world of couloirs and cirques and belays. I enclose the following video to demonstrate the skill needed. I estimate that I screamed “Oh, my god” or words to that effect a dozen times and averted my eyes at least 20 times. Put on your crampons and fasten your carabiner…..

12:38 – Heading back to the hotel now, we took a little side detour up to a few small tarns, which is alpine for glacial pond.

12:46 – The Upper Hooker Suspension Bridge was just as bouncy and windy on the return trip.

12:55 – We walked at the base of Mount Wakefield, which separates Hooker Valley from the Tasman Valley to the east.

12:59 – A small footbridge at the Stocking Stream Shelter took us over the Hooker River with its milky rock flour.

1:20 – Looking down a little later, I saw a drift of Parahebe lyallii.

1:35 – And creeping over a rock was one of the “bidibids”, Acaena saccaticupula.

1:53 – I saw my only Hooker Valley butterfly, the common copper, foraging on New Zealand harebell (Wahlenbergia albomarginata).

2:12 – Coming towards the end of the hike, I made a critical mistake. Weary now and gazing across the meadows at what looked to be a direct route back to the Hermitage, I said, “Why don’t we get off this winding path and go straight back across the meadow?” My husband, trusting soul that he is, reluctantly agreed. Neither of us knew that the only people who ventured this way were mountain bikers. With our tired legs, the spongy soil and long grass of the meadows made the last stretch seem never-ending.

2:14 – In the meadows in front of the hotel were a few lupines. Despite now being on the noxious aliens list, these invaders are quite famous for their massive spring show in the park.

2:19 – Parts of the meadow turned into dried-up gravel stream beds that are clearly part of the seasonal drainage patterns of the rivers here.

2:21 – I found another famous New Zealand mat plant, scabweed (Raoulia australis), growing here.

2:37 – And finally, 4 hours and 20 minutes after we began our hike, we arrived back at the sign-post near the hotel.

3:00 – As we kicked off our hiking shoes and collapsed onto our beds in the 5th floor room with the great view of the mountains, we cracked open a bottle of the Gëwurztraminer we’d bought at Ostler Vineyard the previous day. A glass of chilled wine never tasted so good.

9:30 – And later, after dinner, as the light dimmed in the sky, I looked out on Aoraki Mount Cook with something akin to affection. Like the Māori, I sensed its spirit infusing this spectacular landscape.

9:43 – And as the sun shed its last rays on its snowy peak, I gave thanks for the pilgrimage we had made to be close to it.