Well, I tried. That’s all I could say about my summer 2020 preventive efforts as I watched hordes of gypsy moth caterpillars climbing up our oak trees in summer 2021. Though I probably dispatched tens of thousands of caterpillars with the egg-mass-spraying program I blogged about last year (and those masses completely dried up), there were obviously egg masses too far up in the trees that escaped my control efforts. And before we go any further, I am going to continue to refer to this insect as a ‘gypsy’ moth, since I’ve read rather refreshing and reassuring things from actual Roma people who are proud of their collective name. If I were publishing scientific journals, I would need to abide by nomenclatural consensus, but “LDD moth” (from its scientific name Lymantria dispar dispar) confuses the issue unnecessarily for the sake of this final blog.

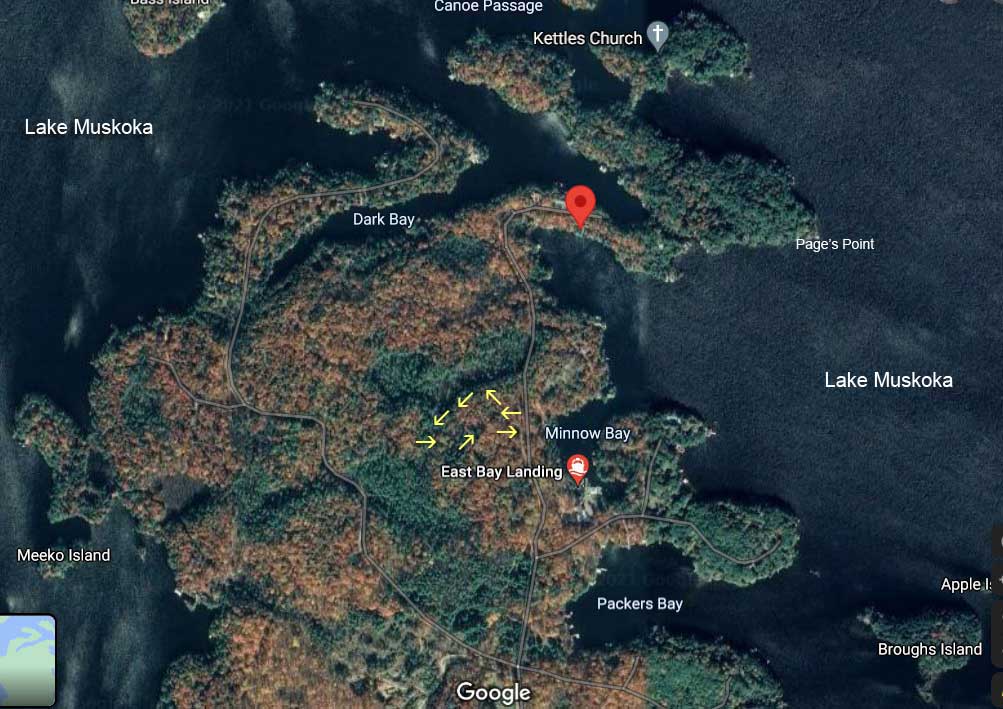

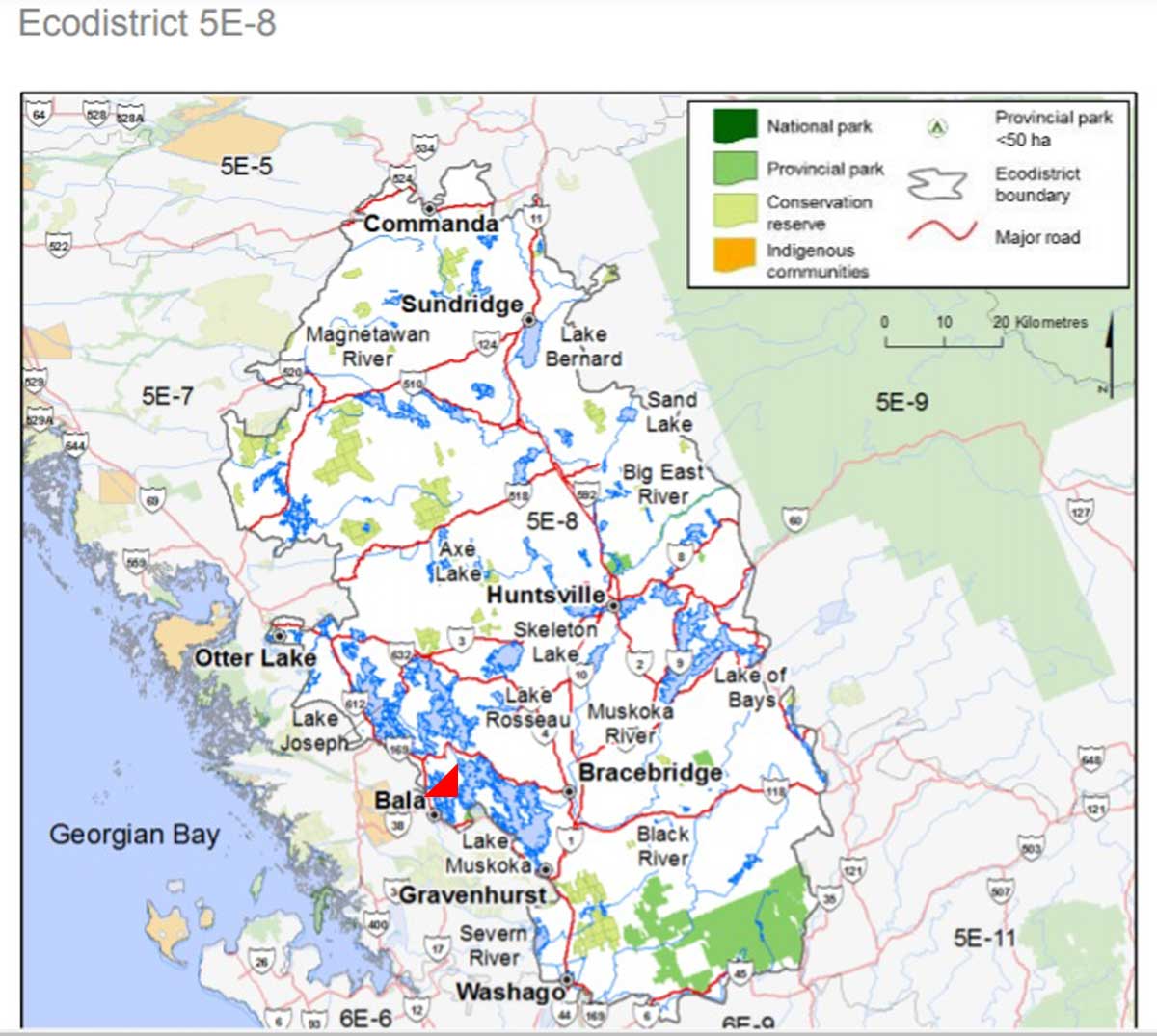

May 20 – Let me take you through this year’s saga in photos, beginning with my pant leg as I sat on our dock on Lake Muskoka, a few hours north of Toronto, on Victoria Day weekend. Those tiny things are the newly-hatched first instars. They were falling freely from the oaks and pines above our heads. But we read reports in the papers at this time of people developing contact rashes from the tiny larvae landing on their necks!

May 22 – I took a spring wildflower walk through the forest nearby and found an early instar on the leaf of striped maple (Acer pensylvanicum). These first and second instars are the stage at which aerial spraying forests with Btk (Bacillus thuringiensis subsp.kurastaki) works, with 2 applications at 7-10 days in age and a second approximately 2 weeks later, while caterpillars are less than 1/2 inch long. Gypsy moth males complete 5 instars; females require 6 instars for the additional energy to produce eggs. Caterpillars feed on foliage for 6-8 weeks before pupating.

Alas, Btk also kills the larvae of native butterflies and moths actively feeding at the time and is increasingly proscribed by governments, which is why I photographed this native moth on our back door. It would be an unintended victim of a spraying program – part of a life cycle of which we may not have intimate knowledge but is most certainly part of the native ecology.

June 2 – When we returned to Lake Muskoka eleven days later, the caterpillars were everywhere, including on our house siding where…

…. in the heat of the day, hundreds climbed up to seek shade on the north-facing back wall, many heading right to the roof eaves.

On the hot, exposed hillside behind our cottage, they were eating the leaves of the many red oaks (Quercus rubra) that grow naturally there. The sound was loud, like Rice Krispies…. “snap-crackle-pop”.

June 4 – As I took a break from gardening, once again I was able to assess the development of the caterpillars on my clothing…

…. and the veiled hat I wear to deter blackflies in the woods.

But some landed on our sundeck and were fair game for the resident ants.

Because of the phenomenon of the caterpillars seeking shade on our north-facing cottage wall, we were able to carry out a program of dispatching them into soapy water. We did this several times a day.

Over several weeks in June and early July, we filled many buckets with caterpillars, not that it did much good. It just made us feel we were doing something to help our trees.

The feeding continued throughout June. I could stand beside a tree and watch a never-ending procession of caterpillars up into the canopy…..

…. where, gradually, the foliage began to disappear on our trees.

When we returned to the cottage on June 23, most of the oak trees looked like February…

…. and our back porch was covered with dried-out oak leaves and male flowers. There would be no acorns produced this summer, one of the seldom-mentioned effects of gypsy moth predation. A 1990 West Virginia study on red oaks said “The high carbohydrate content of acorns provides the energy necessary for winter survival. Loss of mast crops due to direct and indirect effects of gypsy moth defoliation may result in large-scale reductions in wildlife habitat and food sources.” The study mentioned three factors related to defoliation: “direct consumption of flowers, abortion of immature acorns due to low carbohydrate supply, and lack of flower bud initiation

Meanwhile, the caterpillars had begun their assault on our big white pines….

…. leaving our sundeck littered with needles daily.

On July 1st, Doug stood on our dock picking caterpillars off the pines. A drop in the literal bucket, as they say.

Besides the oaks and pines, the caterpillars devoured staghorn sumac leaves….

….. and the foliage of my poor nannyberry (Viburnum lentago)…..

…. and even snacked on some meadow perennials like daisy fleabane (Erigeron philadelphicum).

That weekend I visited one of my favourite wetlands nearby, a place I call the Torrance Fen. Here the caterpillars had stripped the speckled alders (Alnus incana)….

…. and were working on the winterberries (Ilex verticillata).

On June 26th, I took a walk down the dirt road near our cottage and looked at the forest there. Because it is more mixed than our hillside, the damage seemed less severe, but there was still the crackling sound of the caterpillars eating. They were on the young beeches (Fagus grandifolia)…

…. but completely ignored the white ash (Fraxinus americana). Sadly, emerald ash borer has other destructive plans for that species.

Paper birches (Betula papyrifera) and trembling aspens (Populus tremuloides) were stripped bare.

By June 30th, the oldest caterpillars had matured and begun seeking a sheltered spot in which to pupate. Pupae are a dark red-brown with hairs on the exterior; female pupae are larger than the males. They will stay in the pupal stage for 1-2 weeks before hatching as moths.

Some of the aggregations were truly disgusting looking, with tens of caterpillars pupating together.

But on that day, I also noted a lot of withered caterpillars stuck to branches in a ‘backbend’ position, indicating they had died of NPV or nucleopolyhedrosis virus.

If there was any good news this summer, it was that July featured unusually rainy weather – which was not great for people wanting to plan events outdoors, but was the best possible news for our ravaged trees. Refoliation of defoliated deciduous trees requires sufficient groundwater to enable a new round of leaf formation and photosynthesis. Watching the rain fall outdoors actually gave me great joy…

…. and this Canada Day rainbow seemed to augur well for our trees. This year, at least.

I even spent some time on July 4th counting the number of monarch butterfly caterpillars eating the leaves of the butterfly milkweed I’d planted just for them.

And on July 12th, I photographed the new leaves appearing on our red oaks…..

…. even as newly-hatched male gypsy moths flew about in a flurry, seeking the stationary females. The females were everywhere, including in the grooved bark of white pines and…

…even under the plastic tarp covering our firewood pile (and on the firewood itself.)

But on July 14th, it was sadly apparent that the egg masses on trees were much more abundant than in summer 2020. This was one of our worst affected trees. Without sustained cold temperatures in the coming winter, it seems evident that next summer will be even worse, if that’s possible.

So (as in 2020) I mixed up another batch of my horticultural oil solution, attached fresh sponges to my extender pole…..

… .and began the long process of spraying eggs. With the number of egg masses I’ve seen it will be a long process this autumn. But each mass contains a potential of 200-1000 caterpillars so it’s definitely worthwhile to reduce their numbers. And it was evident from last year’s dried-up egg masses that the homemade oil does the job.

I made a video that captured some of this year’s saga, below. Just as a last word, I have read in so many publications that gypsy moths tend to come in cycles of 10 or 12 years, but we have never seen predation like summer 2021 in more than 40 years of visiting and living on Lake Muskoka. If this becomes an annual phenomenon, it will have dire consequences for our tree canopy. Fingers crossed for a cold, cold winter, since extended days of temperatures -25C or lower are reported to be fatal to the egg masses.