In my previous blog, ‘Garden in the Woods – Part 1’, I left you poised to walk around the lily pond of this fabulous native plant garden in Framingham, Massachusetts, outside Boston. I love a garden that features good interpretive signage, so here’s the sign for the pond. Because it’s just May 14th, these marginal plants and aquatics are not yet in flower, but there are still interesting plants to see.

A native plant that is in bloom is golden ragwort, Packera aurea. In my photo below, I show a close-up of the flowers and also a view from the far side of the lily pond of the colony at the base of the slope, illustrating the topography it prefers: moist – but not wet – acidic soil.

In the wet soil near the pond is marsh marigold (Caltha palustris).

I note the ‘Mount Airy’ witch alder (Fothergilla) near the pond and realize why my own fothergilla shrubs aren’t exactly thrilled to be in my unirrigated front garden in Toronto.

The pond edge is wild and natural-looking, with ferns, highbush blueberry and winterberry competing for space.

Royal fern (Osmunda regalis) on the left and cinnamon fern (Osmandastrum cinnamomeum) on the right also grow in the woods near our cottage north of Toronto.

Early-blooming eastern leatherwood (Dirca palustris) is already bearing fruit in the moist soil adjacent to the pond.

I’ve never seen drooping laurel, aka doghobble (Leucothea fontesiana) before, another denizen of damp soil – but normally native further southeast.

As I leave the pond area to continue along the main path, I admire a lovely rustic post and railing. Simple and beautiful.

On the predominately alkaline slope, yellow ladyslippers (Cypripedium parviflorum) are in flower.

There are loads of wild leeks or “ramps” in the valley (Allium tricoccum), a native edible onion that is common in Ontario as well.

Appalachian barren strawberry (Geum fragarioides) grows in the dappled shade down here, too.

Throughout the garden, flowering dogwood’s (Cornus florida) white flowers light up the shadows in May.

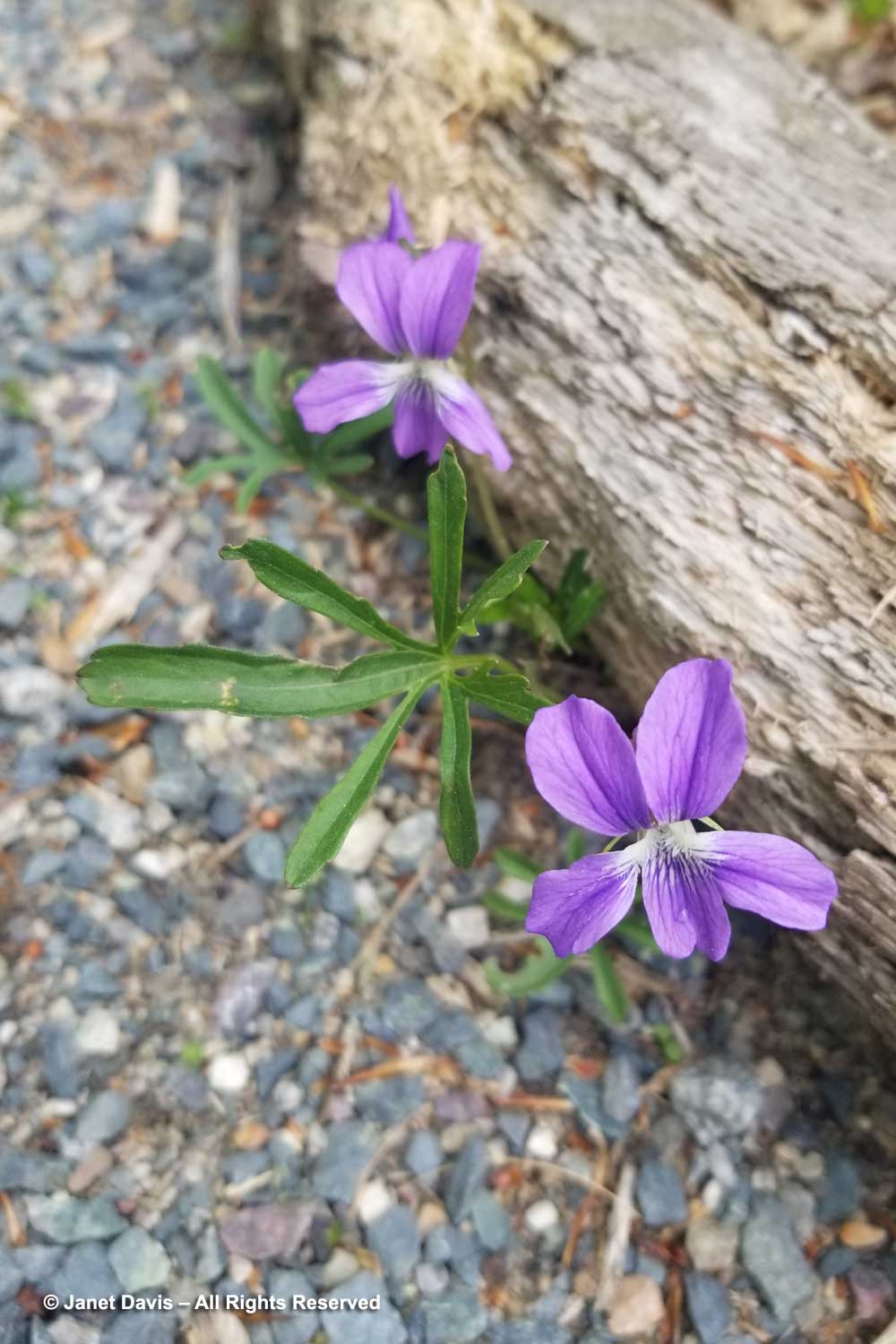

A violet I know well with a large native range, common blue violet (V. sororia).

In the Habitat Display area in the valley, there are a few bogs where eastern skunk cabbage (Symplocarpus foetidus) is plentiful, but its wine-red flowers are long gone…..

….. though the lovely pink flowers of pink-shell azalea are making up for it.

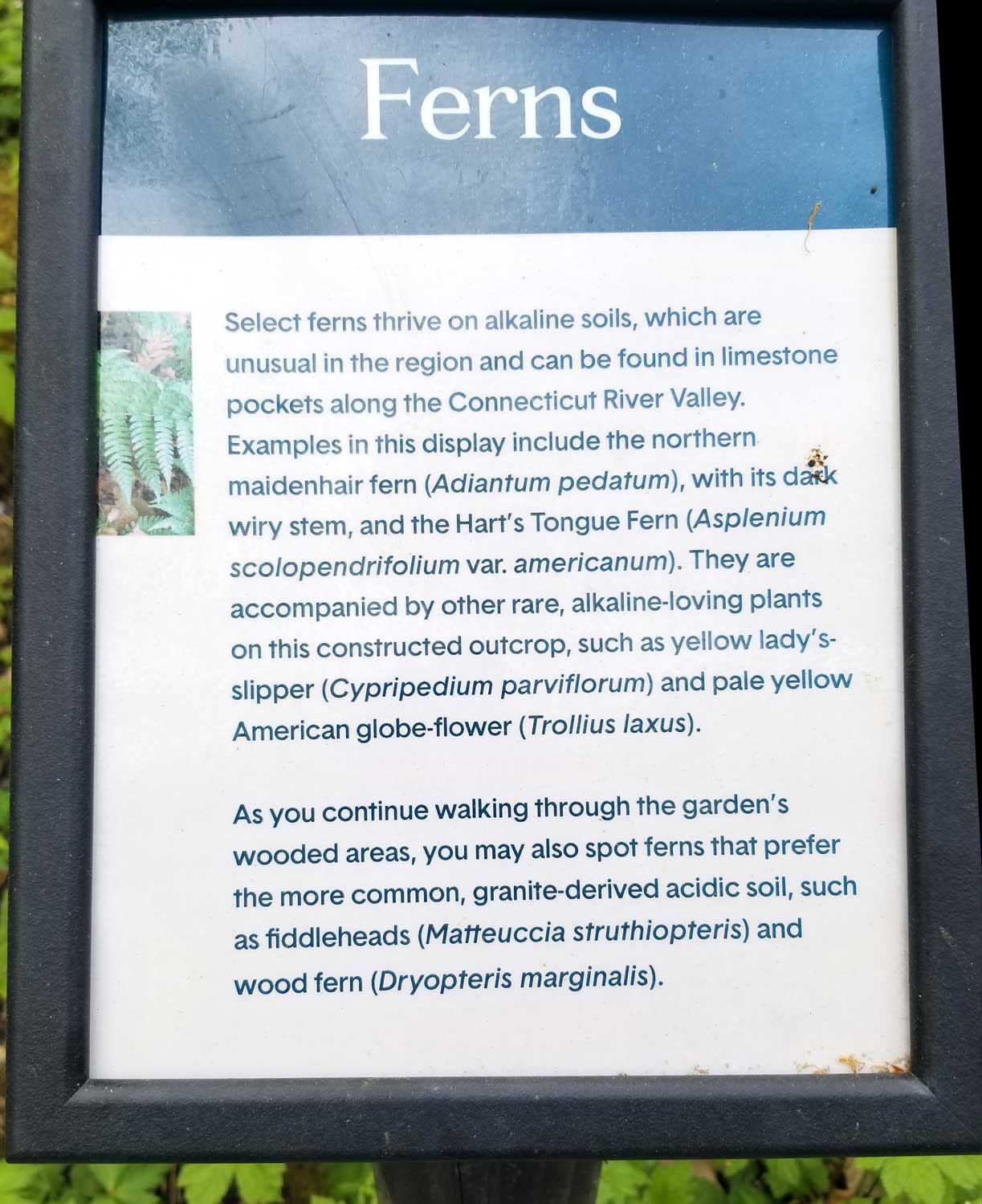

Thanks to the excellent habitat tour on the Native Plant Trust’s website, I’m able to understand a little more about the ecology of some of the areas. Signage is educational, too. This one explains how regional pH determines which ferns require which kind of soil.

This custom limestone habitat was lovely with tall, white-flowered two-leaf miterwort or bishop’s cap (Mitella diphylla) combined with northern maidenhair fern (Adiantum pedatum).

Eastern columbine (Aquilegia canadensis) is familiar to me, since it grows on our cottage property on the Canadian Shield.

I love these vignettes – here is maidenhair fern with rue anemone (Thalictrum thalictroides), a plant that does like acidic soil.

A closeup of rue anemone. Isn’t it lovely?

Nearby is starflower. It also grows in acidic soil in the forest near us though it has a new name, not Trientalis any more but Lysimachia borealis.

Walking on, I come upon box huckleberry (Gaylussacia brachycera). Native to the Atlantic coastal plain and points south, it is a self-sterile shrub that spreads clonally. According to Wikipedia, it is “a relict species nearly exterminated by the last ice age”.

Here and there I spot little pools of pale blue, lovely Quaker ladies or bluets (Houstonia caerulea), another denizen of moist, acidic soil.

The path leads on through rhododendrons not yet in flower.

The Calla Pool has a colony of native wild calla or water arums (Calla palustris) thriving in the muck and sharing the same rhizome, but not in flower quite yet. I am very familiar with this one from our acidic woods on Lake Muskoka north of Toronto.

As the forest clears we come to sunnier areas and a sign describing a meadow ecosystem, which is not much in evidence in mid-May. As the Native Plant Trust says in its video tour: “This meadow provides an example of succession, the gradual change from one ecological community to another. In the colorful foreground you may notice favorite native plants such as partridge sensitive-pea, little bluestem, gray goldenrod, and northern blazing star. Behind the flowers are woody pioneer species such as gray birch, eastern red cedar, and sassafras. Landscapes are constantly changing due to ecological succession, climate change, and disturbances such as natural disasters. These changes allow invasive plants to move in and crowd out native species. Our conservation work includes controlling invasive species, banking native seeds, and augmenting populations of rare plants to ensure their survival.”

For me, the most interesting low-lying habitat in this valley bottom is the ‘Coastal Sand Plain’, which mimics the lean soil of the Atlantic Coastal Pine Barrens ecoregions of Cape Cod and the coastal islands off New England. Two plants of the sand plain grasslands threatened by development are the sundial or perennial lupine (Lupine perennis), below….

…. and prairie dropseed grass (Sporobolus heterolepis).

Another plant of the coastal pine barrens is American holly (Ilex opaca). It prefers moist, acidic soil and, like all hollies, it is dioecious, having male and female flowers on different trees. Thus, if you want those lovely red fruits, you need a male holly to pollinate the female flowers.

Canada rosebay or rhodora (Rhododendron canadense) is showing off its pretty flowers in this habitat, too. Though somewhat scrawny, it is an iconic shrub and lends its name and image to the 120-year-old journal of the New England Botanical Club, fittingly titled Rhodora.

It was so interesting to see this xeric community of the Coastal Sand Plain with prairie dropseed, shooting stars and prairie thistle growing near New England’s (and Ontario’s) only native cactus, eastern prickly pear, Opuntia humifusa.

I’m not sure why I thought of shooting stars (Primula meadia, formerly Dodecatheon) as woodlanders, but these were clearly happy in the sand plain habitat….

…. and included a stunning, dark-pink form.

I’m sure most gardeners would be itching to weed out this thistle, but it is the native pasture thistle (Cirsium pumilum) which is found from Maine to South Carolina. A biennial or monocarpic perennial, it bears scented flowers (its other common name is fragrant thistle) that attract pollinators and its seed provides food for many birds. (But it might not be appropriate for a small garden of natives.)

I am happy to see wavy hair grass (Deschampsia flexuosa) here, a familiar grass in my own rocky, red oak-white pine woodland edge ecosystem at our Lake Muskoka cottage north of Toronto.

And I make the acquaintance of two sand plain violets, coast violet (Viola brittoniana)…..

…… and bird-foot violet (Viola pedata) with its distinctive leaves, whose seed is spread by ants.

There is a different wetland habitat as part of this sandplain and it features Atlantic white cedar (Chamaecypaaris thyoides).

I have never seen swamp pink (Helonias bullata) before, an endangered coastal plain species whose habitat is freshwater swamps and seepage areas. A rhizomatous perennial, its pink flowers with blue stamens are very showy!

Golden club (Orontium aquaticum) is the only extant species in its genus, but there are several identified fossil species from the west coast. It grows in streams, ponds and shallow lakes with acidic soil.

Highbush blueberry (Vaccinium corymbosum) grows in the moist soil edging the pond here.

Heading onto drier ground, I find familiar little Canada mayflower (Maianthemum canadense)…

…. and wild sarsaparilla (Aralia nudicaulis) hiding under a skunk cabbage leaf.

Pitcher plant (Sarracenia purpurea) has found boggy soil and is patiently awaiting an unsuspecting fly.

Evergreen Christmas fern (Polystichum acrostichoides) is an old favourite of mine, perhaps because it stays in one place, unlike ostrich fern.

Circling around to head back to the entrance, we walk through the Beech Forest. As the Native Plant Trust’s virtual tour says: “Maple-beech-birch forests are a classic northern hardwood forest type, representing about one-fifth of forested land in southern New England. Nearly half of beech trees in southern New England have been affected by beech bark disease since the mid-20th century. Despite this insect-fungus complex, the resilient northern hardwood forest thrives in a spectrum of soil and moisture conditions and is home for a diversity of plant and animal species”.

I love this rustic arch leading into the Family Activity Area.

There are no red and yellow plastic slides and swings here – it’s all au naturel and wrought from the forest.

No matter where you travel in North America, if you tour public gardens you’re likely to come upon one of my friend Gary Smith’s magical environmental art creations. This one, part of “Art Goes Wild” completed in 2007 to celebrate the 75th anniversary of Garden in the Woods, is called “Hidden Valley” and it was crafted from fallen logs and branches arranged in a serpentine line.

As we climb out of the beech woods and circle up the hill towards the Visitor Center, I spot sweet white violet (Viola blanda)….

…. and the curved inflorescence of red baneberry (Actaea rubra)….

…. and the white form of crested iris (I. cristata)….

…. and finally, a drift of Allegheny spurge (Pachysandra procumbens), which surely should be a widely-marketed alternative to invasive Japanese spurge (P. terminalis).

We arrive back at the gift shop and I take a quick look at the plants for sale. This one is intriguing taxonomically, because for a long time purple chokeberry was considered a hybrid of red and black chokeberry (A. arbutifolia x A. melanocarpa). But its range outside those species, its viable fruit and unique morphology have resulted in it being given its very own species name, Aronia floribunda.

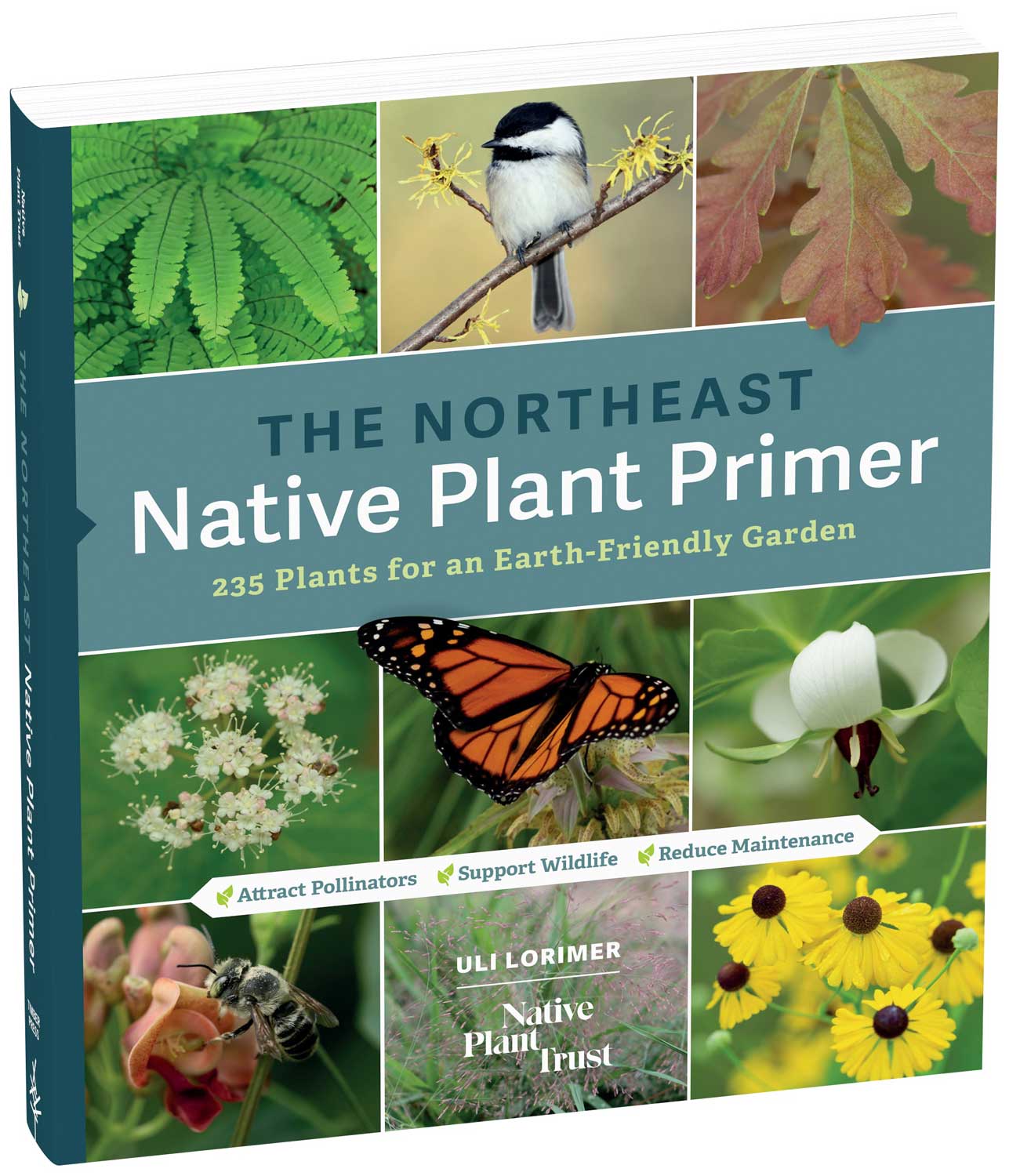

And with that bit of botanical trivia, we depart Framingham’s beautiful Garden in the Woods, filled with respect for Will Curtis’s fulfilled dream and for the breadth of New England’s spring flora. If you want to learn more about what natives can be grown in New England and further afield in the northeast, consider the new book by Native Plant Trust director Uli Lorimer, “The Northeast Native Plant Primer – 235 Plants for an Earth-Friendly Garden”.